Actually, I’m here to tell you that it’s way more! By definition, xeriscaping is landscaping geared to dry climates where little irrigation is available. It involves the cultivation of “xerophytes,” or plants that require very little water, like cacti and succulents. However, today’s interpretation of the concept is much broader, and may be applied to all climate zones. How can this be? Because xeriscaping isn’t just about growing plants where there isn’t much water. And it’s not “zeroscaping,” a derisive reference to some landscapes where the concept was unsuccessfully implemented, or areas where zero landscaping has been implemented. Instead, it’s about growing the right plants in the right places, and grouping plants with similar moisture requirements, to minimize maintenance and conserve water.

What Do We Mean by the Right Plants?

Natives and drought-tolerant non-natives are the best plants for xeriscapes. Planting native plants is a great way to decrease water consumption, save money, reduce maintenance, and save time. Because they are suited to a particular environment, you can give them a healthy start with watering and feeding, and then virtually forget them. Another benefit of natives is that they attract local pollinating insects, birds, and other animals that are genetically wired to seek them out for food and shelter. I recently wrote about native blue wildflowers. Two of my favorites are bluehead gilia (Gilia capitata) and mealy cup sage (Salvia farinacea) They both grow in full sun and require very little moisture. The sage is especially nice at the back of a bed, as it is a bright violet blue, and over two feet tall. The gilia is a lighter shade, and about a foot tall. If you’re looking for a pop of color, blue is a striking choice. If you’re planting non-native varieties, begin by selecting those that have been cultivated to thrive in your climate zone, then fine-tune your choices to those that can withstand water deprivation. Once established, these plants will rarely require watering. Lily turf (Liriope muscari) is a non-native, drought-tolerant clumping ground cover that is used extensively in my area as a border plant.

I never need to water mine, and it shares space with a Knock Out® Rose shrub that also requires little water. When we xeriscape, we group plants by their watering needs. That way, if we do have to water, we can give exactly what each plant requires.

Grouping Plants with Similar Moisture Requirements

So far, we’ve discussed plants that can thrive with little water. However, this is not the end of the story.

Shade-Lovers Unite

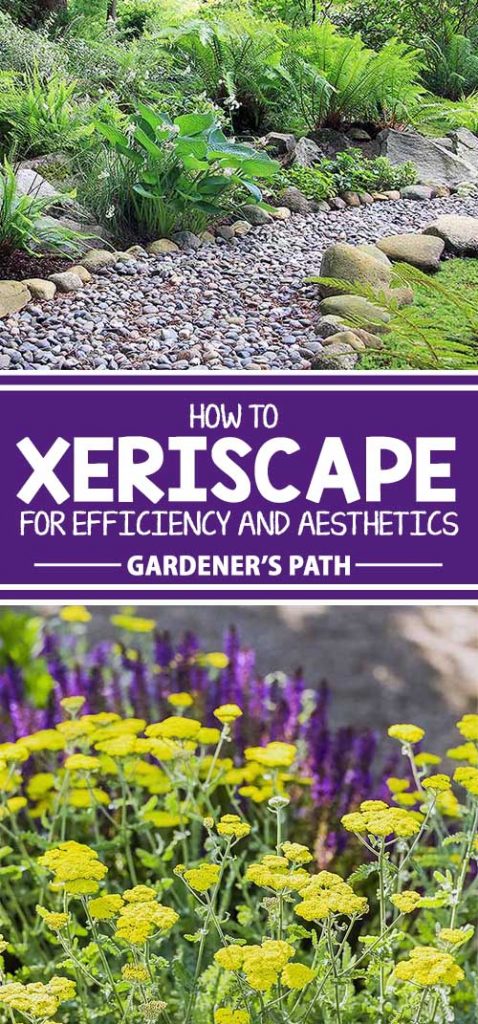

Even in lush areas, where the loam is dark, and rich with moisture, we can practice landscaping with an eye to water conservation and low maintenance. Take, for example, woodland gardening with perennials. Do you have an area on your property that’s very shady, where the soil seems to stay damp? I have a stretch of mature trees that shelter several layers of flora below them, including rhododendron, ferns, hostas, and creeping vinca. I help to keep the area moist by providing a generous layer of organic matter made of mulched leaves, and never have to water this area of my property.

Xerophytes, Take a Bow

This “microclimate” stands in stark contrast to another, in which I have clay-like soil that cracks when it’s parched, and is home to a little rock garden of hardy creeping stonecrop (Sedum spurium) and hens and chicks (Sempervivium). These moisture-retaining succulents are self-sufficient, and I let them spread to their hearts’ content. And if traditional desert-style xeriscapinng suits your climate, I suggest a variety of xerophytes, like aloe vera, agave, echeveria, euphorbia, spineless prickly pear (Opuntia ellisiana), and yucca or flowering shrubs such as turpentine bush.

Kitchen Companions

If you’re growing herbs, look for low-water plants like rosemary, mint, lavender, sage, thyme, oregano, and lovage (Levisticum officinale).

Group them, so that in the event of a drought, you can conveniently refresh the whole gang with a handy watering can.

A Layer at a Time

If you’re landscaping on a grand scale, consider drought-tolerant trees and shrubs like conifers, oak, maple, elm, pine, hickory, redbud, winter berry, forsythia, lilac, serviceberry, and quince. Choose native varieties, or those cultivated for your climate zone. These will provide canopy and mid-level layers of drought-tolerant plants that will thrive with minimal intervention. Also at mid-level are ornamental grasses like sedge, pampas, fountain, and needle, which will add texture and movement to a garden array. At the lower level, perennials such as false indigo, butterfly weed, pinks, and dead nettle are classic low-moisture varieties. And annuals like dusty miller, moss rose (Portulaca grandiflora), cosmos, zinnias, marigolds, petunias, and sunflowers have been favorites of mine over the years.

Minimal Maintenance and Water Consumption

Not all xeriscape plants are completely self-sufficient when it comes to maintenance and watering. Remember, we said that plants need to be nurtured with watering and feeding when first planted. If you’d like to reduce the time you spend mowing, fertilizing, and watering, you might like to replace turf grass with native ground covering plants that are self-sufficient, once established. Alternatively, consider mowing higher (3 inches or more) to allow your lawn to make deeper roots and retain more water. This will save money and reduce storm-water runoff.

As for maintenance, some flowering plants may be improved by pruning leggy stems to retain shape, or deadheading to promote blossoming. Be sure to read plant literature to determine the extent of care to expect with the plants you choose. Low-maintenance varieties will save you time in the garden. Regarding watering, there will be times when there is a drought so severe that you will want to give your plants a much-appreciated drink. But when you do, don’t drag out the hose. Instead, use a watering can and aim the spout at the soil level where the roots are, and not at the plant itself. Watering leaves and flowers is inefficient, and in direct sunlight with extreme heat, may burn the plants. If you select plants that require occasional watering, consider installing a drip irrigation system to water efficiently at the soil level. This is more economical than a sprinkler or handheld garden hose. I recently visited a unique garden that features native species and has an intricate rain watering system. It’s the High Line, a public park in Manhattan that provides a refreshing escape from the bustling city below.

Taking It to the Max

If xeriscaping is all about native plantings and water conservation, the High Line in Manhattan is an amazing example on a grand scale.

This park was once a freight line for the meat-packing district. For years, the defunct rail system was yet another vestige of urban blight. Today, it is a sustainable “green roof” garden trail, and a model for environmentally responsible urban planning across the globe. What an inspiration!

A New Garden Attitude

From Manhattan to our own backyards, xeriscaping makes a positive environmental impact, by creating habitat with native plants, and conserving water with native and cultivated drought-tolerant species. Are you ready to enter a new relationship with your outdoor space, and save time and money at the same time? To briefly recap, here’s what to do:

Select natives, drought-tolerant varieties, and true xerophytes Plan to plant in groupings with similar water requirements Design a layered arrangement to allow plants to shelter one another and preserve moisture Prepare to apply organic compost or leaf mulch to help with moisture retention Check out our xerophytic gardening design guide to get started.

Your xeriscape is sure to flourish! And when it does, you can stretch out on your favorite lounge chair and enjoy the view. Let us know how your gardening is progressing in the comments section below. © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. Originally published January 5, 2016. Last updated May 20, 2017.