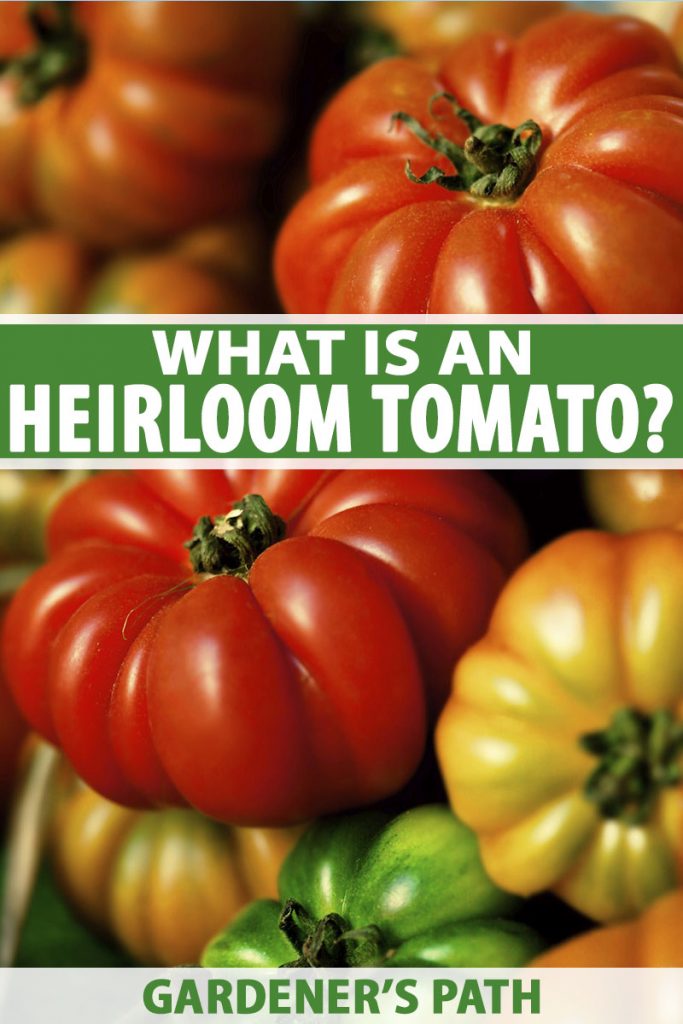

But what is it exactly that makes a tomato special enough to be considered an heirloom? You’re about to find out. Also known as heritage tomatoes, there are hundreds of these time-tested cultivars available in all sorts of shapes, sizes, colors, and patterns. And while grocery store tomatoes are usually pretty much flavorless, the heirloom tomatoes we find at farmers markets or farm stands – or grow in our own backyards – really dazzle the taste buds. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

5 Top Characteristics of Heirloom Tomatoes

Not everyone agrees on exactly how to define heirloom cultivars.

Some definitions insist that the cultivars have to be handed down, much like a cherished quilt. Other definitions focus instead on the length of time the cultivar has been around. But when it comes to tomatoes, all seem to agree on one thing. We’ll start with this.

1. Open Pollination

The most important defining characteristic of an heirloom tomato is that the seed must be produced through open-pollination. This means reproduction takes place the way it would in nature, with assistance from the wind, and pollinators such as bumblebees and other insects.

Since heritage varieties are open-pollinated, they will grow true to type. You can save seeds and grow many new generations similar to the first one – provided you properly isolate your varieties. Save seeds from your heirloom ‘Cherokee Purple’ plants this year, grow the seeds next year, and you will get a new generation of ‘Cherokee Purple’ in your garden.

Seeds for hybrid varieties, on the other hand, are not produced through open-pollination – instead, pollination is carried out mechanically, in a controlled environment. To produce the type of hybrid seed you might buy from a seed company, two different varieties of tomatoes (or more) are chosen with qualities the grower wants to combine – say, one that is bushy, and another that has good disease resistance – and these plants are crossed. The grower pollinates one variety with pollen from the second. These plants then bear tomatoes containing the hybrid seeds that you can buy – the ones that will result in the new improved variety that is both bushy and disease resistant. These seeds are referred to as F1, meaning this is the first filial generation of offspring from two distinct plant parents.

Having these combined traits can be extremely useful – particularly if you are growing these veggies on a commercial scale. However, if you save seeds from that first-generation hybrid – the one that is both bushy and disease resistant – you won’t get a uniform crop of second-generation plants. You may not get any plants at all, in fact, since seeds from hybrids are sometimes sterile. If you do get viable seeds, the majority of them won’t grow true to type, since hybrids are highly variable in terms of genetics. For instance, if you save seeds from your hybrid ‘Early Girl’ plants this year and plant them next year, a few of the seeds you collect may grow into plants and produce fruit that look like ‘Early Girl,’ but the majority won’t. In some cases heritage varieties started out as hybrids, but over time they have stabilized so that they will sow true to type when seeds are self-fertilized. One such cultivar is ‘Trophy.’ Introduced in the late 1800s, ‘Trophy’ was a hybrid intended for market gardeners and canning. This new cross caused a sensation, inspiring many other 19th century hybrids. The genes of ‘Trophy’ eventually stabilized over many generations, so this hybrid is now an open-pollinated variety of historical interest. ‘Trophy’ Hybrids can eventually become open-pollinated through the work of gardeners, farmers, and seed companies. Remember when I said that if you save your second-generation hybrid seeds – these would be called F2 – and planted them the following season, only some of the seeds would grow true to type? If you keep culling the off-type plants and only keep the ones that grow true to type, as long as they are self-pollinated by the same type, eventually the genes will become less variable and may stabilize, and if this happens you will have an open-pollinated variety – a process that can take many years.

2. Passing the Test of Time

But are all open-pollinated tomatoes heirlooms? Nope. At least – not yet. Before calling a variety an “heirloom,” most seed catalogs and growers insist that it pass the test of time as well. There is no commonly agreed upon amount of time required to qualify, however. Some say the cultivar has to be at least 50 years old, some say 100.

Many varieties are even older, with records going back hundreds of years. Think about it – if a variety has been grown from seed, the next generation of seeds have been saved and then handed down, and this has happened over and over for decades or centuries, that variety must be something worth preserving. And when the best plants are saved from a cultivar in one place over generations, you end up with a cultivar that is well-adapted to a certain location. We have these heritage vegetables today thanks to the efforts of generations of seed savers of the past.

3. Cultural Heritage

Many of these seed savers were handing down seeds from generation to generation, as part of their cultural heritage. This handing down of seeds happens among farmers and gardeners, within families, religious groups, tribes, and other communities.

Take ‘Shenandoah’ for instance, a large yellow slicing cultivar that was preserved by Mennonite communities in Virginia, who probably brought it from Mexico in the 1800s. Or consider ‘Reisentraube,’ a cherry tomato variety which was brought to the US by German immigrants, and handed down through generations of Pennsylvania Dutch people as far back as the mid-1800s. And then there’s ‘Nebraska Wedding.’ This orange cultivar was brought to Nebraska in the late 1800s, where it was passed down at weddings to new brides in farming communities. Heirloom Vegetable Gardening: A Master Gardener’s Guide to Planting, Seed Saving, and Cultural History As these varied histories show, heirloom varieties come with reputations as colorful as their skins!

But what’s important to remember is that heirloom tomatoes, just like heirloom quilts or jewelry, are passed down because they have great value to the person handing them down. When it comes to tomato cultivars, seeds may be valued and treated as an heirloom simply because of their taste, but more often this is also because they are well-adapted to the conditions in their particular location – better adapted to a short growing season, or more resistant to sweltering summer days, for example. When I choose seeds for my own garden, that’s why I look for heirlooms from places with a climate similar to mine. Those are always the ones that perform the best on my farm.

4. Unusual Colors and Patterns

The different histories and backgrounds of these veggies provide for a lot of diversity among cultivars. In addition to various shades of red, there are cultivars that ripen to shades of green, white, yellow, orange, pink, and maroon. Some varieties, such as ‘Black Beauty,’ come in hues that are somewhere between blue, purple, and black, and are packed with anthocyanins. And the skins of heritage cultivars often have beautiful, intriguing patterns – stripes, marbling, streaks, splotches, or blushes of pink or red. These patterns are actually linked to flavor in these veggies – I’ll get to that in just a bit. The fruits of these varieties can look like small works of art – and who’s going to complain when edible produce from the garden looks so beautiful? While commercially produced hybrids can be fairly insipid, heirlooms that have been allowed to ripen on the vine have strong flavors – sweet, tart, rich, or a combination of all of these at once. The Heirloom Tomato: From Garden to Table

5. Superior Flavor

Perhaps most important in terms of the experience of eating tomatoes, heritage cultivars have a well-earned reputation for being tastier than grocery store hybrids.

There’s actually a scientific reason for this. Good versus poor flavor is not just the result of soil quality, or an unfortunate side effect of the early harvesting of commercial tomatoes. A plant biochemist by the name of Ann Powell made an interesting discovery about commercial hybrid tomatoes several years ago. She and her colleagues at the University of California, Davis, found that hybrid varieties of Solanum lycopersicum possess a gene mutation that allows the fruits to ripen in a uniform manner – without any uneven, streaky patterns – making it easier for commercial growers to see when their crops are ripe. Unfortunately, this same mutation prevents the sugars in the fruits from fully developing, resulting in fruit with about 20 percent less sugar than heirlooms and 20-30 percent less carotenoids, which are known to impart flavor.

Powell and her team published their findings in Science magazine in 2012, saying that this genetic mutation, which commercial growers had selected for, “inadvertently compromised ripe fruit quality in exchange for desirable production traits.” Now that this mutation has been identified, plant breeders may try to find a workaround and create hybrids without this loss of flavor. In the meantime, our beloved heritage cultivars are already equipped to fully develop their sugars and flavors. So the next time you slice up an heirloom tomato, you’ll know that it’s not just your imagination – they really do taste better than commercial hybrids.

Bonus: Higher Market Value

Speaking of supermarkets, have you ever wondered why you generally don’t find heirloom tomatoes there? There’s a reason for this: The fruits of heritage cultivars are often more delicate and don’t stand up to transporting as well as hybrids. So when you do find them in the supermarket, you can bet that they are locally grown.

These varieties are also generally more prone to cracking, are less reliable producers, and often don’t have the same level of pest or disease resistance that hybrids have been bred for. Overall they can be a somewhat riskier crop to grow, and aren’t typically used for large scale commercial production. Having said that, they are less common – and what is rare is cher. So if you’re thinking about running a farm stand or taking your produce to a farmers market, these veggies have an advantage over hybrids – they fetch a higher price. Heirloom tomatoes are well-suited for selling at farm stands, farmers markets, and of course, enjoying straight from the backyard garden.

And while heritage cultivars may not be as high yielding as hybrids, you’ll save money on seeds.

Seeds of Heritage

Now that we’ve reached the end of our exploration of these wonderful summer veggies, I bet you’re ready to grow your own now.

Check out our article on the best heirloom tomatoes, where you can learn all the details about 21 top cultivars. As for me, some of my favorites are ‘Cherokee Purple,’ ‘Thessaloniki,’ and ‘Black Krim.’ What about you – what are your favorites? Let us know in the comments! And if growing your own tomatoes is on your mind, here are some more articles on these summer garden staples to read next:

How to Grow Tomatoes from Seed in 6 Easy Steps The Top 10 Reasons to Love Tomatoes and Add More to Your Diet What’s the Difference Between Determinate and Indeterminate Tomatoes? How To Identify, Prevent, and Treat Common Tomato Diseases

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Bloomsbury USA, Hirt’s Gardens, and Voyageur Press. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.