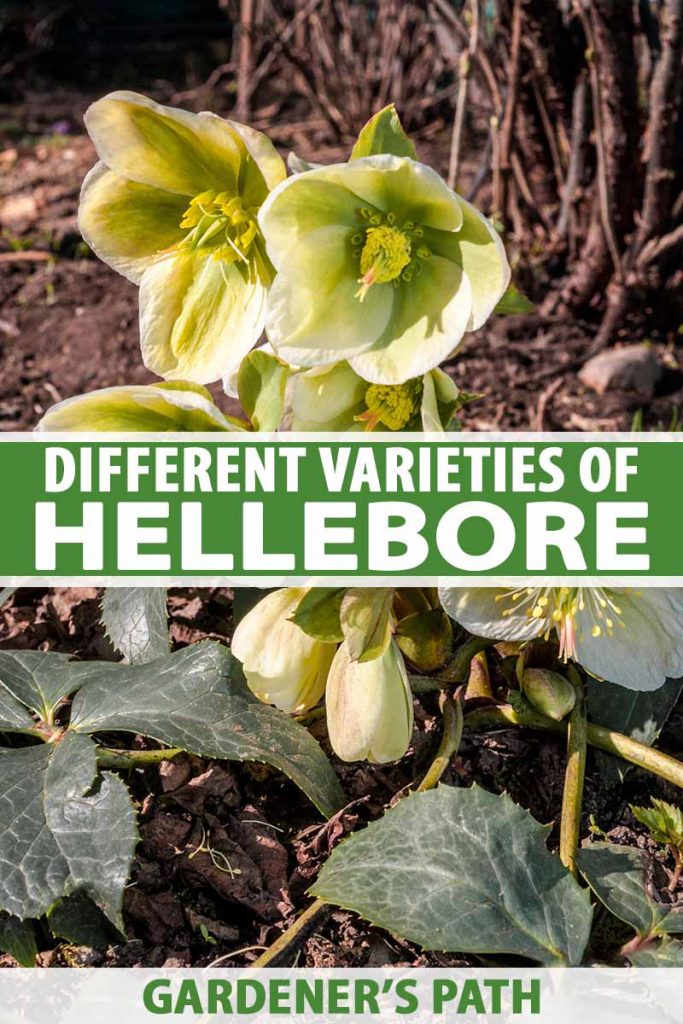

It’s not one plant, but a family of approximately 20 species, plus various subspecies. And it’s often called the Lenten, Christmas, or Winter rose. Most hellebores grown in the home garden are assorted H. orientalis hybrids that are collectively referred to as Helleborus x hybridus. They offer a “potluck” color palette, and bloom during the late winter to early spring period when many other plants are still dormant. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. In this article, you’ll learn about how the members of the varied Helleborus genus are grouped for classification, as well as the key features of the major species to date.

Classifying a Genus

Perhaps the most unique feature of hellebores is the wide variety of characteristics that exist among these plants. Even within a single species, you may find different sizes, colors, leaf shapes, and petal or sepal traits. Experts in the plant world grappled with distinguishing one species from another until 1989, when British botanist Brian Mathew wrote a monograph on hellebores that still stands as the definitive classification of the genus. In an effort to bring order to a mishmash of identified hellebore species, Mathew examined their physical characteristics, and discovered that they all fit nicely into one of six basic botanical types. He assigned each one to its proper section and the Helleborus genus finally had a classification system. It is still in use today. As time passed, Will McLewin, one of Mathew’s colleagues and an intrepid hunter of hellebores in their native Balkan region, and two other botanists, Michael Fay and Hang Sun, continued to study the genus. In 2001, they presented “The Molecular Phylogeny of Helleborus” to the botanical community. It questioned the classification of H. thibetanus, the only hellebore purported to be of Asian origin, and criticized the catch-all nature of the Helleborastrum section. Debates within the hellebore community continue and will likely result in further fine-tuning of this classification system in the future.

Six Unique Types

At this time, there are approximately 20 different recognized hellebore species. Every one fits into one of Mathew’s six sections of classification. Let’s look at the defined sections, examine the species in each, and discover their unique characteristics.

1. Syncarpus

This section’s name derives from the word “syncarpous,” meaning to have three joined sets of reproductive organs, or carpels. There is only one species in this category. It is H. vesicarius, a rare plant that is very challenging to grow. It has nondescript green flowers that measure a tiny 3/8 to 1 1/2 inches wide, and look like tiny cylinders with an opening at the bottom. If it weren’t for a prominent maroon band, they would blend in with the leaves and probably go unnoticed in the garden. Most noteworthy about this plant are the especially large, conjoined carpels, or seed pods. They start out green and turn brown, protruding to a length that’s about three times as long as the flowers. Unlike most varieties, instead of producing individual seed pods, those of H. vesicarius unite to form one large pod. And instead of opening to disperse seeds, the pod clings to the stem until a breeze blows it away. Another unique characteristic is that after going to seed, this plant spends the summer in dormancy, while other types continue to grow. This is a caulescent, or stemmed species. It is deciduous, dropping its leaves in summertime. There is a mound of soft, deeply divided, medium-green leaves at the base. The bracts, or tufts beneath the blossoms, are leafier than those of most types, and are considered to be true leaves, unlike those of most varieties, which are very sparse. Mature heights reach 18 inches. H. vesicarius is suited to USDA Hardiness Zones 7 to 9. Bloom time is from late winter to early spring.

2. Griphopus

Plants in this class have narrow, divided leaves that resemble the feet of a mythical griffin. To date, there is one, H. foetidus. It is also known as the bearsfoot, bear’s foot, or stinking hellebore – the leaves sometimes have a musky odor when they are crushed. The flowers of this kind are about one inch in diameter, chartreuse, and cylindrical. Sometimes the lips are tinged with maroon. This is a caulescent, or stemmed plant. The smooth, dark blue-green, leathery foliage is evergreen. It consists of basal mounds of deeply cut, narrow leaves with serrated edges, and leaf bracts of lighter green beneath the blossoms. Mature heights may reach three feet. This type is suitable for growing in Zones 5 to 9. Bloom time is from late winter to early spring. There are two species, H. argutifolius, and H. lividus, both caulescent types that have thick stems.

3. Chenopus

In this section are plants with leaves that consist of three segments, like the foot of a goose, or in Greek, “chen” or χήνα (“chína”). There are no leaves at the base of these. Instead, leathery green foliage is clustered at the tops of stems that reach three to four feet tall at maturity. The leaves are deeply serrated and have a long middle lobe and two shorter side ones. H. argutifolius is the holly-leaved hellebore. It is also known as the Corsican hellebore, H. corsicus, from an earlier classification. The flowers are light green and cup-shaped. They measure one to two inches in diameter, and open only partially. This variety is best grown in Zones 5 to 9. Expect blossoms from late winter to early spring. In addition to true species plants, there are cultivars of H. argutifolius available as well, including ‘Janet Starnes,’ a variety with variegated green and white leaves. H. lividus, the Majorcan hellebore, resembles H. argutifolius with its three-part leaf. However, its blossoms exhibit hues from pale green to rose, and the foliage is glossy and veined prominently in white. The mature height of this plant is 12 to 18 inches. It is more tender than H. argutifolius, and grows best in Zones 8 to 9. Flowers bloom from late winter to early spring. H. argutifolius

4. Helleborus

Despite all hellebores having the Latin “Helleborus” in their name, the only member of Mathew’s Helleborus classification is H. niger, aka the Christmas rose. Sometimes H. niger is also called the black hellebore. This is somewhat confusing, because the color refers to the dark roots of the plant, and not the petal-like sepals. H. niger is known for having showy, star-like blossoms that face outward instead of downward in the usual nodding fashion. They are snowy white and gradually fade to pink, then green. Most are between one-and-one-half to three inches, although larger ones can occur. ‘Onyx Odyssey’ You can find seeds for the ‘Onyx Odyssey’ variety available from Burpee. H. niger is an acaulescent plant, with short flower stalks of approximately six inches that rise directly from its fleshy rhizomes, rather than clustering atop true stems. Sometimes the stalks are a purplish color. There is a mound of leathery, dark-green basal foliage. The leaves are palmate, meaning that they fan out like fingers, with seven to nine segments. There may be some serration at the tips. H. niger grows to between 9 and 12 inches tall at maturity. This plant is evergreen and thrives best in Zones 3 to 7. It blooms from late winter to early spring. In addition to the true species, there are numerous additional cultivars available with noteworthy features, like the three-inch blossoms of ‘Potter’s Wheel’ and the mid-December bloom date of ‘Praecox.’ There are also two subspecies of H. niger: H. niger ssp. niger has flowers that measure 2.75 inches across. H. niger ssp. macranthus is known for having the largest flowers, up to 3.75 inches in diameter, and blueish-grayish green leaves.

5. Helleborastrum

This section is somewhat of a catch-all, and it won’t come as a surprise if it eventually undergoes further fine-tuning. The species it contains are crossed frequently to produce hybrids labeled somewhat generically as Helleborus x hybridus.

Currently included in this expansive section are:

H. abruzzicus H. atrorubens H. bocconei H. croaticus H. cyclophyllus H. dumetorum H. liguricus H. multifidus H. occidentalis H. odorus H. orientalis H. purpurescens H. torquatus H. viridis

These plants are all acaulescent, producing flower stalks directly from fleshy rhizomes. Some exhibit color variations within a single classification. There are numerous subspecies and hybrids in existence. It may be difficult to find true species – particularly of the rarer types – for the home garden; however, hardy crossbred varieties abound. Here are the highlights of each:

H. abruzzicus

If you ever find yourself strolling through the mountainous regions of northern Italy and come across a pale to lime green flower with deeply divided, serrated, fern-like green foliage, it may well be H. abruzzicus. Not classified until the early 2000s, H. abruzzicus is still coming into its own. It’s not well known or widely available, and precise market descriptions are typically vague. One UK purveyor describes the flowers as “relatively large.” The sepals are slightly more pointed than round. This is a deciduous type that drops its leaves at season’s end. The basal leaves are bright green, finely divided, and serrated, with a pedate tendency. The height of this plant is a petite 8 to 12 inches. It’s suited to growing in Zones 6 to 9. Bloom time is later than most – don’t expect to see flowers until spring.

H. atrorubens

One of the first to bloom in late winter, this type fades as spring gets underway. It has smaller blossoms that are slightly pointed and measure one to two inches. The flowers tend to face outward instead of nodding in a downward direction. Colors range from dark purple to bright green, often with purple backs and green undersides. The stems of this kind tend to branch more than other types. The medium-green leaves are deeply divided and sometimes subdivided in pedate fashion, creating an almost circular perimeter. Each segment is narrow, smooth, leathery, and serrated at the tips. New foliage may be tinged with purple. This is a deciduous variety that drops its leaves at season’s end. This plant reaches a height of 12 to 18 inches at maturity, and is suited to Zones 6 to 8. Bloom time is late winter.

H. bocconei

Formerly classified as a subspecies of H. multifidus, H. bocconei hails from the mountainous regions of Italy and is still somewhat rare to find in cultivation. UK purveyors describe the flowers as “medium-large,” with a scent similar to elderberry or currant. They are light green, yellowish-green, or yellowish-white, and shaped like saucers. Medium green, smooth, leathery basal leaves have jagged serration, and deep divisions and subdivisions in pedate style. This is a deciduous type that drops its leaves at the end of the growing season. Petite plants generally top out at 12 inches, but sometimes reach twice this height. They bloom early, often at the beginning of winter. H. bocconei should thrive well in Zones 5 to 8.

H. croaticus

H. croaticus is a Croatian species with one- to two-inch flowers that are similar to those of H. torquatus. They may be purple or green, or purple shading to dark green on the undersides. The sepals are slightly pointed and have prominent purple veining. The best way to tell this species from others with similar coloring is to look for fuzzy hairs on the nodding flower stems, or pedicels, and on the undersides of the leaves. This type is deciduous and drops its leaves, going dormant early, at summer’s end. The foliage of H. coraticus is similar to that of H. atrorubens, being medium green, with a mound at the base and some beneath each blossom. Unlike the soft leaves of other deciduous types, those of H. croaticus are somewhat leathery. They are serrated and have three deeply divided segments arranged in pedate style. This plant reaches between 8 and 16 inches in height and is suited to growing in Zones 4 to 8. It blooms in late winter.

H. cyclophyllus

H. cyclophyllus has green to yellow-green bell-like blossoms that measure one to two inches in diameter. Some nod, while others face outward. The sepals are slightly pointed and the flowers may have a musky or slightly sweet odor. This kind is acaulescent with deciduous foliage that mounds at the base. The soft leaves are of medium width, serrated, and noticeably thick. They are segmented in pedate fashion, and form an almost circular perimeter. There are three main parts, some with further subdivisions. H. cyclophyllus is similar to H. odorus. There are two ways to tell the difference: H. cyclophyllus does not have joined carpels, and its new foliage is reddish with fuzzy hair, as opposed to the smooth and leathery green foliage of H. odorus. Mature heights are between 16 and 20 inches. It does best in Zones 6 to 9. This plant is one of the earliest winter bloomers.

H. dumetorum

Still relatively rare in the home garden, H. dumetorum is considered fragile in comparison to others. The flowers are commonly described as “small,” and for a hellebore, that means about an inch in diameter. The sepals are light green and slightly pointed, cup-shaped, and nodding. This is an acaulescent, deciduous plant that is sometimes dormant by summer’s end. Soft basal foliage may start out reddish, but matures to medium green. The leaves are narrow and pedate, except in some cases, when they are arranged in a horseshoe shape. There are three main leaf segments that are further subdivided. They have fuzzy hairs on their undersides, and are thinner in texture than most species. Mature heights range from 8 to 12 inches. H. dumetorum thrives in Zones 4 to 8. Bloom time is from late winter to early spring.

H. liguricus

Known as the Ligurian Lenten rose, this species originates in the northern coastal regions of Italy, and is still relatively rare in the home garden. The flowers are considered large in comparison to other plants classified as Helleborastrum, meaning they are likely to be at least two inches in diameter. They are saucer shaped with slightly pointed sepals that are white to greenish-white, often with white backs and green-tinged undersides. The flowers are scented and have been described as both sweet and lemony. In addition to the color, the foliage is a distinguishing characteristic of this plant. It is pedate, but much less segmented than that of other species. And it is soft, deciduous, and medium green. This plant matures to a height of approximately 15 inches. It should thrive in Zones 5 to 8, and blooms from late winter to early spring.

H. multifidus

Green to purple saucer-shaped flowers with slightly pointed sepals characterize H. multifidus. There are numerous subspecies that vary slightly from one another. Some are all green, while others have purple backs and green undersides, purple-tinged edges, and completely purple sepals. The foliage of this type also varies widely. Mounds of basal leaves are pedate, often with 20 to 45 segments, many of which are further subdivided. They are smooth, leathery, and jaggedly serrated. This is an acaulescent type that may hold on to some of its leaves year-round. However, some subspecies go dormant by summer’s end. Mature heights range from 8 to 14 inches. It is well suited to gardens in Zones 4 to 8. Bloom time is from late winter to early spring.

H. occidentalis

H. occidentalis was considered a subspecies of H. viridis until it was reclassified by the team of Mathew and McLewin. It has nodding heads of light green that measure approximately one to two inches in diameter. The sepals are slightly pointed. This is a deciduous type. Somewhat fragile basal leaves are dark green, shiny, and jaggedly serrated. They are pedate, or foot-like, and consist of two main segments that exhibit an additional three to six divisions each. Mature heights range from 8 to 16 inches tall. This plant does well in Zones 4 to 8, and blooms from late winter to early spring.

H. odorus

The two- to three-inch blossoms of H. odorus, or fragrant hellebore, can have a musky odor, or they may be scent-free. Colors range from chartreuse to green. They open to a shallow saucer shape. A distinguishing feature of H. odorus is the slightly joined carpels that become evident when the seed pods begin to swell. The foliage of this variety mounds at the base and is smooth and leathery. It is sparse in the bracts beneath the blossoms. Colors vary from dark green to yellowish-green. The leaves are lance-like, of medium width with prominent serration. They are arranged in pedate, foot-like style, and consist of three main segments, some of which are further subdivided. Unlike many hellebores, this one has fuzzy hairs on the leaf stems, or petioles, as well as the leaf undersides. H. odorus reaches a mature height of between one and two feet, and may hold on to some of its leaves from one growing season to the next. It is best suited to Zones 6 to 8, and blooms in late winter.

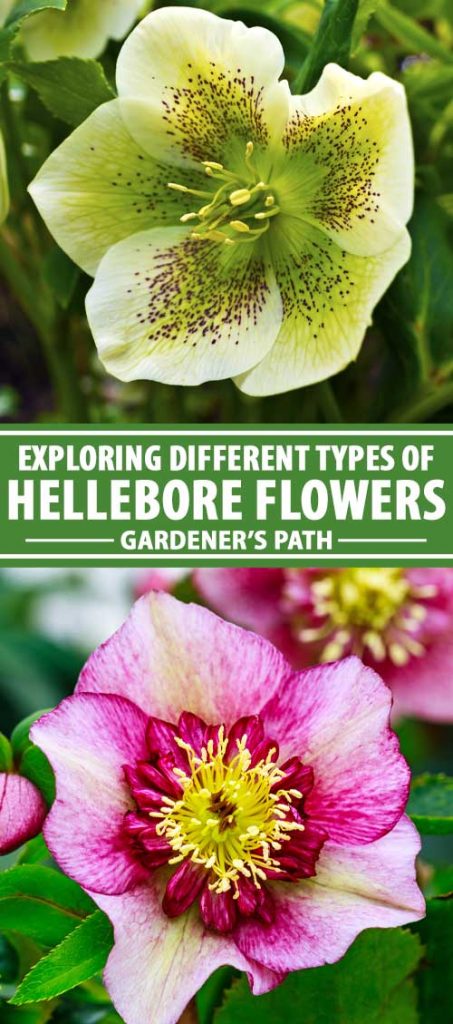

H. orientalis

Commonly known as the Lenten rose, H. orientalis exhibits numerous colors and forms and is exceptionally hardy, making it the most frequently cross-bred variety. There are so many plants that originate in this section that the cultivars are collectively called Helleborus x hybridus. From whites and yellows to greens, pinks, and purples, there are single and double varieties in abundance from which the home gardener can choose. There are three subspecies of H. orientalis:

H. orientalis ssp. guttatus has white flowers with purple speckling. H. orientalis ssp. abchasicus has reddish new foliage, and flowers that start purple and fade to pink. H. orientalis ssp. orientalis has showy white blossoms.

This type is deciduous, dropping its leaves at season’s end. It reaches a mature height of 12 to 18 inches, and is best suited to Zones 4 to 9. Bloom time is from late winter to early spring.

H. purpurascens

H. purpurascens has cup-shaped purple flowers that range from one to two inches in diameter. The undersides of the sepals are purple or bright green. The soft, medium-green foliage of this plant is deeply divided into multiple narrow segments. Being deciduous, it drops its leaves at season’s end. Mature heights reach between 8 and 12 inches. This species is suited to Zones 4 to 8, and blooms early in the winter.

H. torquatus

The one- to two-inch flowers of H. torquatus nod or face outward. The sepals are bell-like, with deep purple backs and green undersides. Sometimes you’ll find striping on the undersides. The striping and deep purple color make H. torquatus a popular plant for hybridizing. The foliage consists of soft green leaves tinged with purple. Each has a pedate, or foot-and-toes, arrangement of multiple narrow, serrated segments. This species is deciduous, dropping all of its leaves at the end of the growing season. Mature heights are between 9 and 12 inches. It is suited to growing in Zones 4 to 8, and blooms in late winter.

H. viridis

Sometimes called the green Lenten rose, this type has blossoms with a diameter of one to two inches, and powder-green, pointed sepals. H. viridis is deciduous. The foliage is palmate, or fan-like, and consists of segmented green leaves that are narrow and glossy, with jagged serrated edges. It reaches a mature height of 12 to 18 inches, does best in Zones 6 to 9, and blooms in early and mid-spring.

6. Dicarpon

The final section of Mathew’s classification contains species that have two joined seed-containing carpels. To date, there is one such plant, H. thibetanus, the only hellebore to originate in Asia, as opposed to the Mediterranean. There is some debate over its origin, so changes may be forthcoming! H. thibetanus is a relative newcomer to the US hellebore market. It was identified in China in the 1860s, but was not available outside its native land until the 1990s. It is characterized by partially open, bell-shaped blossoms that may nod or face outward. Crisp sepals may start out white and fade to pink and then green. There may be purple veining. The sepals are pointed, unlike the rounded ones of many types. This is an acaulescent plant with stalks that rise directly from fleshy rhizomes. The soft, light-green foliage beneath the blossoms is comprised of serrated leaves with seven to 11 segments each. A noteworthy fact is that unlike the other species, and most plants, H. thibetanus does not produce cotyledons, or the embryonic seed leaves of indefinite shape that usually come first when seedlings sprout. Instead, true leaves appear from the start. This plant is deciduous. It can reach a mature height of 18 inches, and is suited to Zones 6 to 8. Bloom time is from late winter to early spring. In addition to the true species, there are cultivars available as well. ‘Tie Kuai Zi’ is a white variety with a pink eye and slightly pointed sepals.

Hybridization

Plants available for purchase may be true species, or hybrids of two or more types. In addition, some are bred to enhance what was once a mutation, the formation of a row of petals inside the outer row of sepals, called “doubling.” You can read more in our guide to the different varieties of double hellebores here. If you look for some of the rarer plants with no success, contact your local hellebore society or noted breeders directly. Hellebore species are frequently crossed to produce hybrids. When two or more different species in the same section are crossed, the result is called an interspecific hybrid. An example of this is Helleborus x hybridus, the cross between H. orientalis and another species in the Helleborastrum section.

When two or more species from different sections are crossed, the result is an intersectional hybrid. For example, Helleborus x ballardiae is the result of crossing H. lividus, of the Chenopus section, with H. niger, of the Helleborus section. It has the pink coloration of H. lividus and the generously sized blossoms of H. niger. In addition, not all crosses will result in fertile seed, and hybrid seeds that are viable produce varied results.

Purposeful Planting

With this background on the Helleborus genus, you’re ready to confidently introduce unique new plants to your outdoor landscape. Feel free to converse knowledgeably with purveyors of plants and seeds, as well as other growers. Hellebores: A Comprehensive Guide

You now have an understanding of which plants are rare, and may be pleasantly surprised to learn that their successful cultivation may earn you a coveted place in a local hellebore society or horticultural competition. In addition, you’ll join the ranks of environmentally-conscious gardeners who plant for wildlife. How? When you choose to grow late-winter to early-spring-blooming hellebores, you provide a valuable food source for bumblebees who often struggle to find nectar-rich plants during this time. If you want to learn more about the fascinating world of hellebores, you’ll need these guides next:

How to Propagate Hellebores How to Divide and Transplant Hellebores 7 Tips for Planting Hellebore Seeds