While potatoes are the most high-profile victims of this menace, a variety of stored products can be afflicted, ranging from carrots to tomatoes. Conditions in the field can predispose stored produce to rot. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. We at Gardener’s Path will review the steps you can take to save your food from these pernicious rots.

Pathogens that Cause Bacterial Soft Rot

The classic causal agents of bacterial soft rot are bacteria that were formally known as Erwiniabut have been renamed:

Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp. carotovorum (Erwinia carotovora ssp. carotovora) Dickeya dadantii (Erwinia chrysanthemi)

In addition, some species of Clostridium, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas can also rot stored foods under certain conditions.

Vegetables and Fruit Affected

While woody plants are not prone to soft rot, many other kinds of plants are. In fact, early research on how Erwinia causes disease was conducted on African violets. Some of the many types of plants that can contract bacterial soft rot include:

Potato Tomato Carrot Squash Melons Pumpkins Cucumbers Cauliflower Cabbage

Symptoms

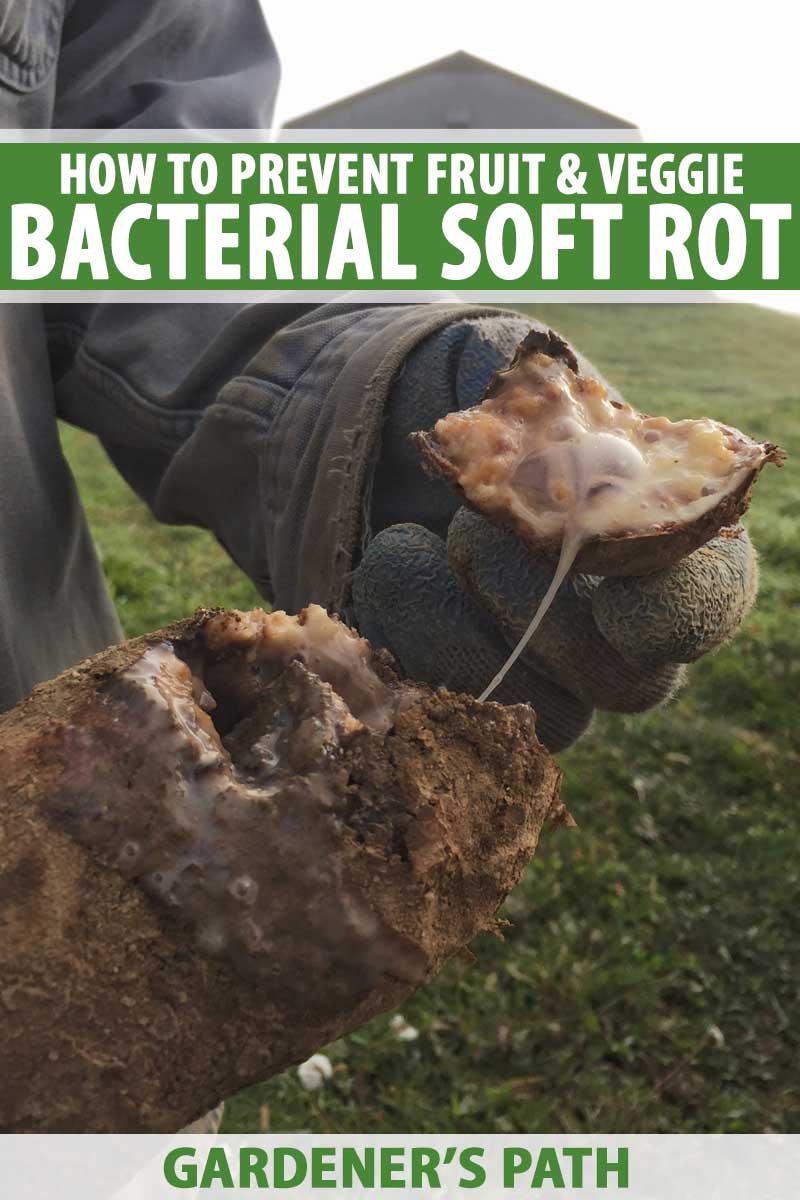

While the end product is a slimy smelly mess, the earlier phases are more subtle. The first indication that your produce is on its way out will be water-soaked spots. At this point, the food smells fine. The spots grow larger over time and then become sunken and soft. Next, the tissue underneath starts to dissolve and becomes discolored and mushy. As secondary organisms invade the diseased tissue, it begins to smell. Unfortunately, there is no cure for produce at this stage, and you should immediately throw it out or burn it. Do not put it in your compost pile because the bacteria can live in the soil.

Factors That Encourage Soft Rot

Bacterial soft rot is predominantly a disease of warm humid conditions. For example, potatoes that have been harvested at temperatures over 80 F are more likely to rot in storage. Your crops can decay between 45 and 90 F, but the process really accelerates when the temperature exceeds 70 F. Harvesting from excessively wet fields can result in the development of soft rot. A film of water on stored produce can encourage the development of this disease by reducing the amount of oxygen in the plant tissue. Produce that has been wounded is much more likely to rot in storage. In addition, plants that are grown without adequate calcium are more likely to subsequently decay. The bacteria that cause this group of diseases are easily spread mechanically or by insects. For example, infected soil on your hands or tools can spread the pathogens. Often, they will colonize plant tissue that has already been infected by a pathogen. These are known as secondary infections.

Prevention Techniques

Control starts in the ground! Since wounds provide entry points for the bacteria, try to control insects like cabbage maggots that wound produce. Disinfect your tools frequently. Bleach can be hard on metal, so consider using 70% alcohol. Practice good sanitary conditions while you harvest. For example, potatoes harvested during muddy conditions are more likely to rot in storage. If you do have to harvest in wet conditions, ventilate the produce until it is dry before putting it in storage. Remove as much soil as you can before storage, since the soil can limit the movement of air. If you will be shipping your produce, make sure that the vegetables have dried after washing before you ship them.

Bacterial Soft Rots are Among the World’s Worst Plant Diseases

Losing potatoes and other types of crops to bacterial soft rot is a worldwide problem and causes enormous losses. High temperature and large quantities of moisture are conducive to the development of this disease.

While there is no cure once your produce is infected, you can take steps to minimize the chances of developing this suite of diseases. Have you been able to slow or stop the development of bacterial slow rot in your crops? Let us know how you fared in the comments. Check out all of guides on our sister site, Foodal, for more information on storing produce. © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.