Just the mere mention of this disease or its common symptoms is enough to send terror coursing through a rose grower’s heart. That’s because this disease is absolutely devastating, turning your shrub into a disfigured, weak little thing before killing it outright. And there is no cure. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. In this guide, we aim to clarify what causes this disease and what you can do about it, because believe me, I know how calamitous it can be. I lost more than one shrub before I figured out that there was more I could do beyond ripping out my plants and considering a different hobby. Here’s what I’ll cover, coming right up: Rose rosette disease (RRD) is such a problem that experts around North America have joined together to try and figure out a solution. Experts associated with big names like the USDA, the University of Georgia, the American Rose Society, the University of Florida, Monrovia, and Texas A&M are all working to improve testing for RRD and to breed resistant cultivars. But you don’t have to wait for them to start addressing the situation in your own garden.

What Causes the Disease?

Ready for a quick biology review? This disease is caused by a virus, which is a microscopic infectious agent that needs a living host to reproduce. If you don’t remember from biology class, a virus is made up of nucleic acid that is housed in a shell of protein. Viruses are responsible for ailments in humans such as the common cold, herpes, and measels. In plants, viruses cause all of the various mosaic virus diseases, ringspot disease, and many wilts. The pathogen that causes this disease is carried by the mite Phyllocoptes fructiphilus, though the research is still out on whether it might also be caused by additional species in the genus. People commonly refer to the pathogen as rose rosette virus, or RRV. By the way, the disease is called rose rosette disease and rose rosette virus interchangeably, though the latter is technically a reference to the pathogen that causes the disorder, while the former is the name of the disease itself. While we’ve known about this disease and what the symptoms looked like since the 1940s, we didn’t know what caused it until 2011, when researchers figured out it was caused by a virus.

The History of Rose Rosette Disease

At this point, RRD has spread across most of North America, but it first appeared in western Canada, California, and in the Rocky Mountain states in the 1940s on wild multiflora types (R. woodsii). As of 2002, it had spread east and reached most of the midwest and the south. Today, it has spread even further to almost every state, since it is popping up on cultivated plants in stores. Cases have been documented in every state in the continental US at the time of this writing except Oregon, Montana, North and South Dakota, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. If you live in one of these states and suspect your plants are infected with RRD, let your local extension office know right away. You can also report the disease on the roserosette.org website, which is funded by the USDA. Reporting is key to helping experts track and, hopefully, eradicate the problem.

Symptoms of RRD

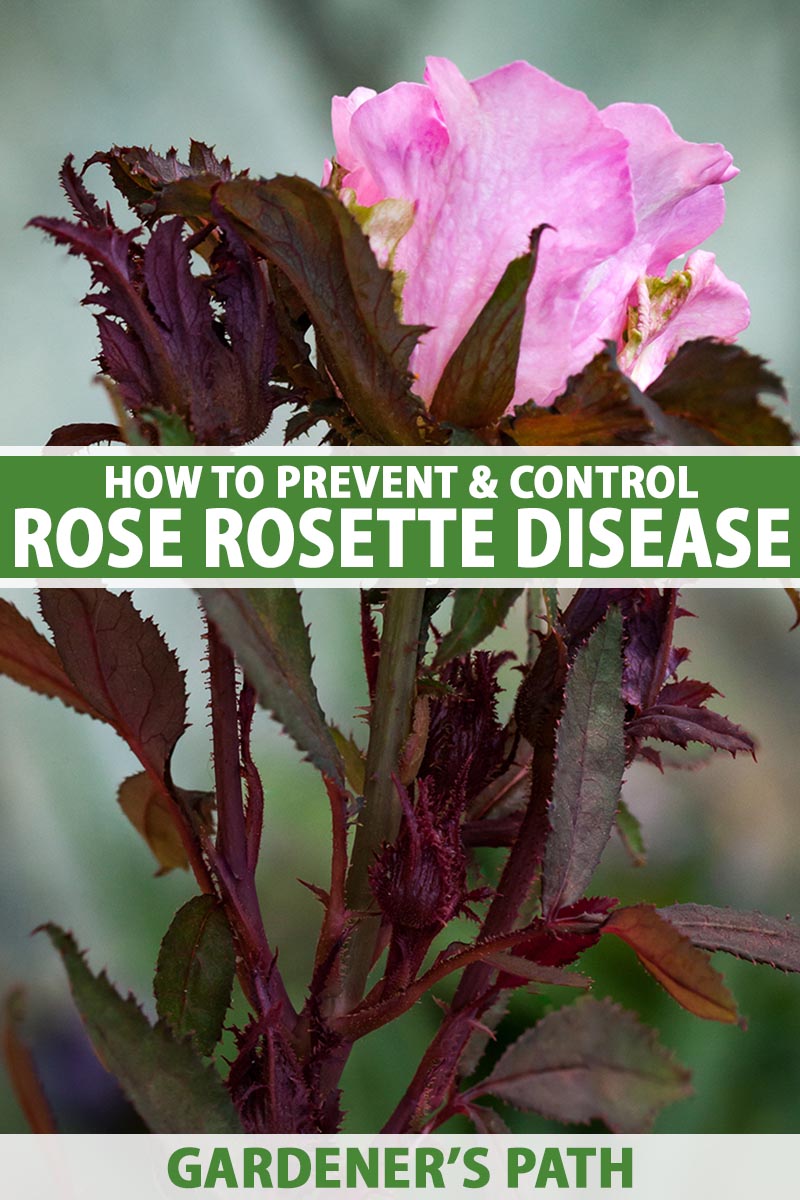

Once you learn to recognize RRD, it’s pretty distinct from other diseases, even with its many strange symptoms. The most obvious sign is the witches’-broom growth, which is a bundle of multiple small stems at the end of the main stem. It does look a bit like a broom, so it’s aptly named. Witches’-brooms can also be caused by the overuse of glyphosate or other herbicides, so don’t rely on the presence of these growths alone to diagnose plants. The virus can also cause elongated stems, mottled leaves in red or yellow, and thickened stems. If you see red or purplish stems or leaves on a cultivar that doesn’t typically have them, that’s a strong warning sign. Another telltale sign is an increase in the number of prickles, usually called thorns. These will often be softer and smaller than standard prickles in infected plants, but there will be far more of them. If you’re growing a cultivar with few or no prickles and it starts forming them, or if one or more stems are covered in far more prickles than others on the bush, you should suspect RRD. Also look for distorted bud and leaf growth, discolored flowers, or dying stems and branches that wither and turn black at the end. If flowers develop – which isn’t a guarantee, if this disease is present – they might be discolored or distorted, or they might not open at all. Any or all of these symptoms may impact random branches here and there, or the entire plant. But it doesn’t matter if a certain branch isn’t showing symptoms – it has the disease in it either way, if any part of the shrub shows clear signs of infection. RRV is systemic, which means the virus moves throughout all parts of the plant when it is present. Overall, infected plants will be less vigorous, less able to withstand cold winter weather, and seem to fall prey to all the other diseases roaming around out there. Within a few years, the plant may die, either due to the virus itself or secondary infections. If you only note one of these symptoms, don’t assume your rose is safe. RRD can be present even if there are no obvious symptoms, and an infected plant may never develop more than one symptom before it succumbs.

How RRD Spreads

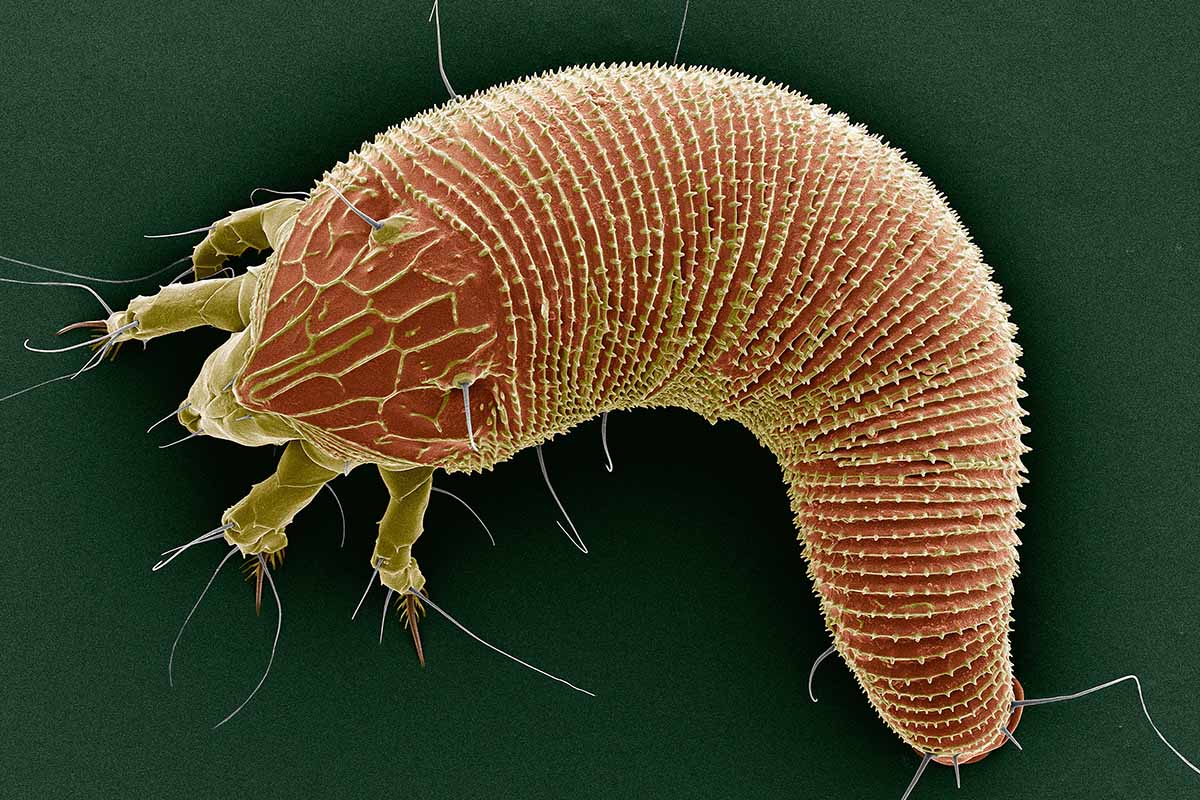

There are several ways that this disease can be spread from other impacted plants to your own. Most notably, the disease is carried by mites, those common insects that feed on our rose plants. Infected eriophyid mites carry the disease with them wherever they go, transmitting the virus as they feed on plants. If you prune your rose that’s infested with mites and then use the pruners on another plant, you can spread the mites, and the virus. Say you unknowingly graft a crown onto infected rootstock – you just introduced RRD to your new plant. While you might have seen mites in the garden or even had an infestation on your plants before, you might not know how to identify an eriophyid mite. If you’ve ever seen a spider mite, you know they’re tiny. But eriophyid mites are four times smaller than that, and they’re invisible to the naked eye. If you could take a look at them under magnification, you’d see brownish-yellow bugs with four legs. Unfortunately, since they’re so small, the only way to know they’re present (besides sending in your plant to a testing facility) is to look for the symptoms of RRD. They can walk to nearby plants, travel on clothing or gardening tools, catch a ride on the wind (they’re that small!), or hitch a ride on a plant brought into the garden. They cannot live in soil or on non-Rosa plant material, however. If they were to catch a ride on your pruners, they couldn’t live for days and days without finding a new host plant.

Species Commonly Impacted

Technically, any Rosa species can be infected by RRV, but wild roses – R. multiflora, in particular – are the most commonly impacted. They are often the hosts that carry the disease and enable it to spread. If you have wild roses growing in your area and your region has documented cases of RRD, it’s highly likely that the disease is lurking nearby, just waiting for a mite to carry it along to your garden. No roses are safe from RRD. Even those that resist many common diseases, such as Knock Out, Drift, and Buck cultivars, are all susceptible. To date, researchers have tested over 900 Rosa cultivars and have found about 50 that show promise in developing resistant cultivars. The prairie climbing species, R. setigera, appears to be one that shows natural resistance. But resistant doesn’t mean immune. Don’t worry, RRD won’t infect any other plants in your garden. Even other rose relatives in the Rosaceae family such as raspberries, apples, and spirea are all safe. That’s the good news. Now for the bad news…

How to Treat

I’ll get the bad stuff out of the way first. There is no known cure for RRD. That’s part of what makes it so devastating. If you don’t want it to spread to your other plants, your neighbor’s roses, and the entire neighborhood, you’ll have to pull and destroy the infected plant. You can’t just cut it out at the ground level, either. This virus lives in the roots, so you’ll need to remove all of those, too. Some gardeners opt to leave the roots in place but consistently kill any suckers that pop up. Whatever you do, don’t plant any roses there again until you’re sure the roots are dead. The mites can’t live long without a host. If you cut the crown off of a rose plant but left the roots in place, the mites could survive on the roots as long as the plant material is still moist and alive. Once the roots die, the mites rapidly follow. You never know if this disease will stick around in your garden to torture you, impacting all of your roses, or if you might just have one infected plant and then it never returns again. It’s not worth the risk, though. Fortunately there are steps you can take to prevent reinfection and spread.

Preventing RRD

First of all, a healthy plant is more likely to fend off a mite attack. Don’t compost it or toss it in the woodpile. You need to burn it or seal it in a bag and toss it in the trash. You can also completely bury the plant matter and allow it to die. Next, apply a miticide to any nearby roses in case you released the mites into the air as you were removing the infected plant. Bifenthrin Concentrate Forbid Miticide Remove any suckers that pop up in the same spot. As long as suckers are emerging, the roots are alive and the mites are still hanging out. Finally, if you have multiflora types on your property that you don’t want, remove them to reduce the chances that they’re hosting the disease and will cause it to continue to spread. I know it’s not always possible to keep your plant totally healthy at all times, but do your best to support it by providing the correct amount of water, food, sun exposure, and protection (if necessary). To learn more about raising roses, check out our guide. You can’t prevent the mite that spreads this disease from infesting your plants in the same way that you can with larger mites, such as by releasing or encouraging predatory mites in the garden or washing them off the plant. But there are lots of things you can do to limit their spread. Examine plants carefully before bringing them home. If you see any sign of RRD, don’t let them anywhere near your garden. To be extra safe, quarantine any new plants for two weeks, if possible, before placing them in the ground. It never hurts to spray with one of the miticides mentioned above when you bring it home as well. Also, always wash your tools in between uses. If you prune one rose plant, clean your pruners with a solution of one part isopropyl alcohol and nine parts water. This goes for your shovels and rakes, too. Never take a cutting or graft from any rose that shows symptoms of this disease. If you’ve been working on a plant or have touched one that has RRD, don’t go near any other roses until you have washed and changed clothes. Keep an eye out for any wild roses in your neighborhood. Alert any property owner if you see signs of RRD and explain the situation. You should also remove any from your property if you know RRD cases have been reported in your area. Better safe than sorry. When you do any winter pruning, discard any cuttings. Don’t leave them in the garden. The same goes for fallen leaves. Be sure to remove any dead leaves or debris as soon as you notice them, and bag up the debris rather than tossing it in the compost. If you use a leaf blower in your yard, never use it around your roses unless they’re completely dormant. That includes wild roses, too. Leaf blowers can send the mites flying around your yard. Try to provide 20 feet or more of space between your roses, with other species placed in between, if possible. Taller plants are ideal, because they can act as a barrier for mites being blown on the wind. The populations of mites are concentrated in the blossoms and this will help prevent them from spreading. Discard or burn the deadheaded blooms. In the winter, use an application of dormant oil to smother any mites that are present. Arbico Organics carries All Seasons Dormant Spray Oil in ready to spray or concentrated options, in a variety of sizes to suit your needs. Apply twice during the dormant season. All Seasons Dormant Spray Oil Be aware that birds, deer, or rabbits (as well as humans) can carry the mites on their bodies. You can’t do much about birds, but try to remove any wild roses that sit along a deer path and try not to plant shrubs where deer travel frequently. Finally, interplanting with non-rose plants can help prevent the spread of the mites. Using one of these methods alone won’t be enough. You need to implement several (or all!) of the integrated pest management options mentioned here to have the best chance at keeping the disease away. Fortunately, some of the biggest names in gardening and botany are collaborating to try and create resistant roses. Once someone cracks that code, you can be sure that it will hit the market shortly after. That should be welcome news to anyone who has suffered because of this disease. If your plant already has it, it’s too late to save it. But you can save the rest of your roses if you’re willing to put in the effort. If not, geraniums are lovely, too (I kid!). What method did you find most helpful in preventing RRD in your space? Or which do you plan to use? Let us know in the comments. We have a lot more information to share on growing roses if you’re interested in expanding your knowledge. If so, here are a few topics to get you started:

7 Common Reasons Why Roses Drop Their LeavesHow to Transplant Rose BushesHow to Winterize RosesTips for Planting Roses During the Fall