Believe it or not this coveted tree crop has been cultivated from as early as 4,000 BC – and shows no sign of dropping out of fashion any time soon. In the same family as other firm favorites such as peaches, cherries, plums, and apricots, almonds provide a delicious, nutritious, and extremely versatile addition to any homestead or garden. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Beautiful as well as delicious – what’s not to like? As often is the case with beautiful things, these delicious nuts come with a few hang-ups… read on to find out more about what it takes to grow almond trees.

Cultivation and Historical Use

Cultivated as early as 4,000 BC, almonds (Prunus dulcis) are thought to be native to central and southwestern Asia, although their exact ancestry is unknown. Throughout history, these nuts have had a lot of religious and cultural importance. They even merit a mention in the Bible, when in the Book of Numbers, Aaron’s rod blossomed and bore almonds. The Romans also held a special place in their hearts for almonds, showering newlyweds with the nuts as a fertility charm, and there are records suggesting that they were a prized ingredient for Egypt’s Pharaohs. Today, some Americans give out sugared almonds at weddings, as a representation of children, happiness, romance, good health and fortune. In Sweden, they are hidden in cinnamon-flavored rice puddings at Christmas to bring luck in the coming year to whoever finds them. Explorers are supposed to have eaten them while traveling the Silk Road between Asia and the Mediterranean, where it didn’t take long before they took root and flourished, especially in Spain and Italy. Today, we often associate the nut with California, although they actually weren’t introduced there until the mid 1700s, when they were brought over from Spain by the Franciscan Padres. They didn’t immediately take to life in California, however, and it took years of research and crossbreeding to help them adapt to their new, cooler life on the coast. By the 1870s, they’d cracked the problem (along with many, many nuts in the process) and now they are firmly established in California’s Central Valley.

Growing Conditions

Almonds are sensitive souls, and are fussy about their growing conditions, which unfortunately means they can be about as challenging to grow as they are delicious. The trees require hot and dry conditions, thriving in USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 7 through 9 as they especially enjoy areas that have long summers with hot, dry, sunny weather, and therefore a long growing season. That being said, they also have a need for a certain amount of cold – around 200 to 500 “chill hours” per year at temperatures less than 45°F (7°C ) – to successfully break the dormancy of their buds. This is why they’re not well adapted to tropical climates. They are particularly intolerant of wet soils and frosts, and as such are well suited to places like California and the East Coast. This is a problem for the early flowering almond, which is particularly vulnerable to frosts. P. dulcis loves the sun. Although they will tolerate partial shade, they won’t flower or fruit nearly as well as they would if planted in in full sunlight. Although they prefer well-drained, deep, loamy soils, they will tolerate other soil types, including poor soils, as long as they are not wet or poorly draining, which they absolutely cannot abide. Conversely, and somewhat counter-intuitively, the trees need ample rainfall – around 500 to 600 millimeters or 20 to 25 inches annually – or irrigation to produce good yields and well-filled nuts, although they will survive with less water. Traditionally, they weren’t irrigated until farmers discovered they responded well to just the right amount of help given at the right time. They especially benefit from extra watering in early spring, during the summer, and sometimes during the first months of autumn, but really need a helping hand at the beginning of the growing season, as starting off the season too dry can result in a significant decrease in production. However, it is important not to water them around or near harvest time, with commercial growers stopping irrigation around three to four days before harvest. This means it’s a bit of a guessing game when growing these, and you have to find just the right balance to achieve a good harvest. Almonds are generally not self-pollinating, so cross-pollination with a second variety is usually required for fruit production.

Recommended Varieties and Cultivars

When choosing your tree, the most important thing to keep in mind is your growing conditions, and which hardiness Zone you’re in. Another top tip is to make sure you buy a sweet almond if you plan to eat the nuts rather than a bitter almond tree, typically an ornamental which is grown more for aesthetic reasons. There are quite a few standard varieties, including ‘Carmel,’ which gives an excellent, well protected nut and is also an excellent pollenator, and ‘Mission’ which, despite being a late bloomer, is a very productive tree. Before planting, the roots should be given a thorough dosing with water, ensuring that they’re thoroughly wet before they are put into the ground to to get them off to a good start in life. ‘All-In-One’ is exceptional as one of the few self-pollinating cultivars, so it has no need of a neighbor for a helping hand in making fruit, adding to its value for the small space gardener. The fruit from this tree ripens in late September or early October, and it is considered a soft-shelled nut. ‘All-In-One’ You can find ‘All-In-One’ trees available from Nature Hills Nursery. For a slightly hardier variety, ‘Hall’s Hardy’ is a good bet. This cultivar is just as often planted for its beautiful pink blooms as for its nuts. Ripening in October, it is a full-size almond tree that does better with a a buddy for cross-pollination, so be sure to plant another variety nearby for a good harvest. ‘Hall’s Hardy’ You can find bare root ‘Hall’s Hardy’ trees available from Home Depot. ‘Hall’s Hardy’ is very cold tolerant – in fact, it even requires a bit more a chill to produce fruit, so this is perfect for slightly more marginal places, recommended for Zones 5 to 9. ‘Nonpareil’ is one of the most popular commercial cultivars. Most of the nuts you find at the grocery store are ‘Nonpareil.’ This cultivar is partially self-fertile, but for maximum yields you’ll need to plant a buddy of a different variety. ‘Nonpareil’ This full-size almond tree is suitable for cultivation in Zones 6 to 9. You can find four- to five- and five- to six-feet-tall trees available from FastGrowingTrees.com. Another option is ‘Penta,’ a Spanish cultivar grown commercially in Europe. The monounsaturated fat content of these nuts is higher than that of most other cultivars. ‘Penta’ is disease-resistant and hardy in Zones 6 to 9. Another partially self-fertile cultivar, harvests will be larger if you plant a different variety nearby. ‘Penta’ FastGrowingTrees.com carries four- to five-foot trees.

Proper Planting Practices

As with all trees, giving them a proper start in life is the key for their future success. Almonds like a healthy distance from their neighbors, ideally 15 to 20 feet (four to six meters) apart. The hole should be dug wide and deep enough for the whole root system, with special attention given to the tap root so that it’s not bent out of shape. As with many nut trees, almonds are especially sensitive to tampering with their tap root, so they should never be trimmed or forced into a hole that’s not big enough to accommodate it. The rest of the roots should also be sensitively handled, and carefully spread out to prevent matting. They should be planted to the same depth they were grown at the nursery (you should see the noticeable color difference between the roots and the rest of the plant, which indicates which part should be buried). This is the same for both bare root plants and potted trees. Soil should be firmly compressed around the roots as you refill the hole. Once the hole has been refilled, you should give your baby tree two buckets of water to settle it in well to its new home. At this point, you can also give your tree a little boost by adding some fertilizer, though it is best to wait until spring to fertilize if planting in the fall.

Propagation

Like most fruit and nut trees, almonds are normally propagated by budding. This is by far the easiest and most effective way to grow them and ensure that they grow true to their parent plant.

By Root Graft

A hardy root stock (often of peach or the more resilient bitter almond variety) is used to give the tree resistance to soil-borne diseases, and then the fruit-bearing branch is grafted onto the root stock. Using grafted almonds makes the trees much more resilient, and they often grow much faster than from seed. This is particularly the case for those that have a peach root stock, which generally tends to be more productive than those grafted with almond root stock. A further complication with almond trees is that you have to have at least two different, but compatible, varieties so that they can cross pollinate, usually via bees.

From the Nut

It’s perfectly acceptable to try growing your own from seed for a backyard project, as long as you are aware that it will take much longer to bear fruit, and any nuts that are produced may not be of the same quality as that of the parent plants. Find fresh nuts – not roasted like you find in the supermarkets. Leave them to soak for around 48 hours, and then place them on a wet paper towel in a plastic bag and place them in the refrigerator. About three to four weeks in the refrigerator should do the trick, and the almonds should start sprouting. At this point, they’re ready to pot in a nice, well-drained soil mix (something like a mix of sand and compost) and placed in direct sunlight, ideally on a windowsill where it’s nice and warm. The important thing is to keep them moist, but never soggy. After they have reached about six inches in height, they’re ready to be moved up to a bigger pot size.

Pruning

Pruning has different purposes at different stages of the tree’s life. Pruning young almond trees determines their future shape, and therefore their productivity and the quality of the nuts produced. It’s important to get it right to ensure a good harvest. Almonds are commonly pruned into a “vase” type shape with three to four main branches, which also allows for ease of harvesting. If done correctly, the “vase” shape makes the tree more vigorous, more productive, and guarantees a longer lifespan. Pruning after maturity, however, is more about maintaining the shape established in the early stages of the tree’s life. Pruning renews the tree and stimulates it to produce more. Around 20 percent of an older tree’s canopy should be pruned back each year. For more information on proper pruning practices, check out our guide.

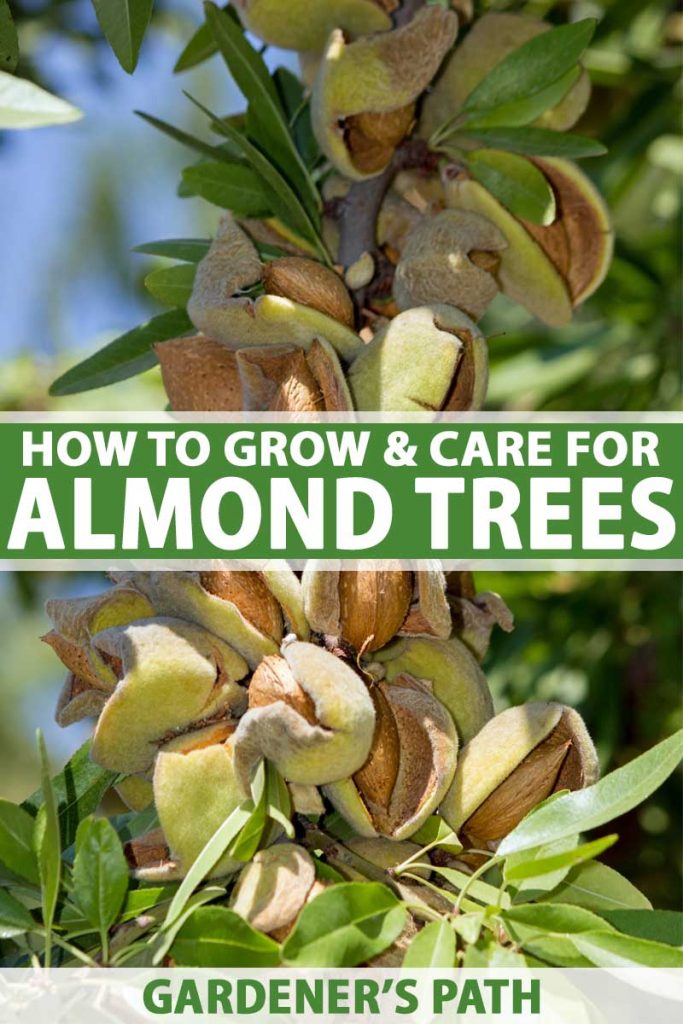

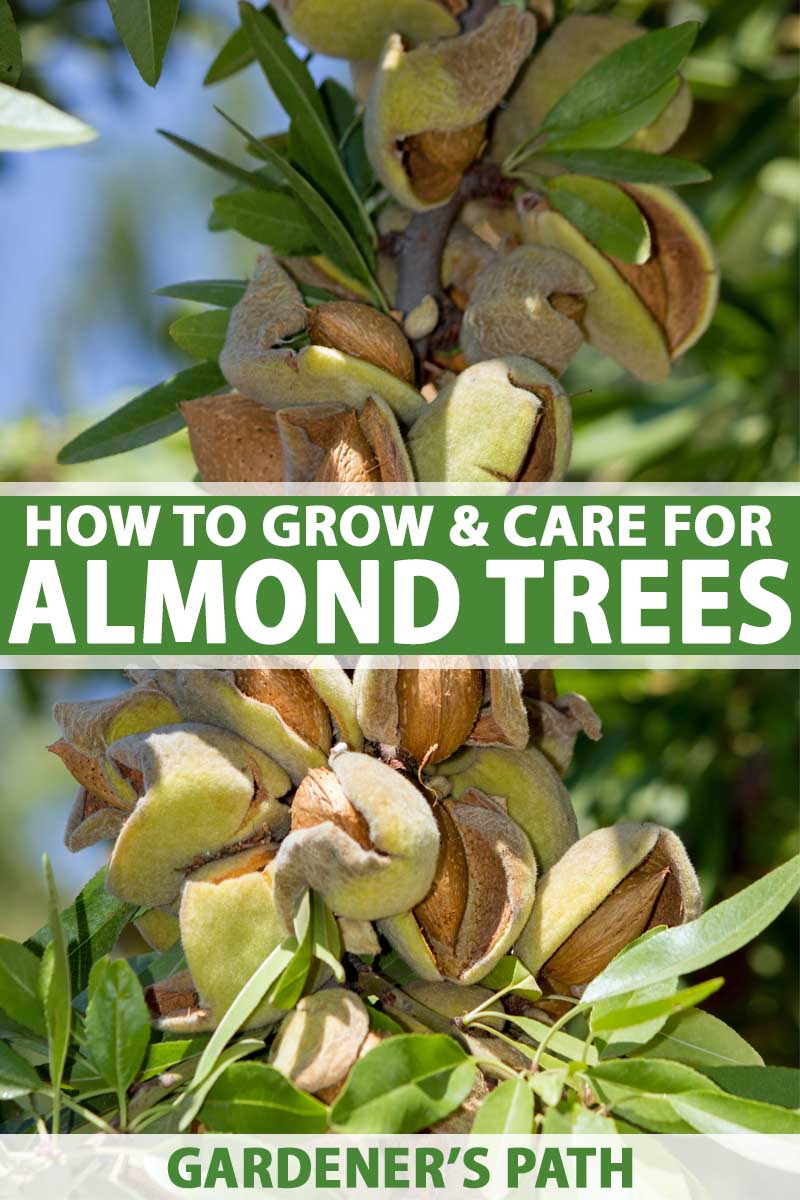

Harvesting

Harvesting looks really fun, and that’s because it is! Safely wrapped up in their shells, all it takes is a hard shake to make the nuts fall to the ground, where they can be gathered. Top tip: it’s best to shake the trees over a sheet so they can be easily collected afterwards. You’ll know they’re ripe for a picking (or a shaking) when the hulls start to split open, often from late summer through to October in the US. If you wait until about three-quarters of the nuts have started to split, it’s a safe bet to harvest them. The nuts must be dried before consumption, which can either be done by leaving them on the ground for a few days after shaking them (if there’s no risk of rain where you are), or storing them safely somewhere cool and dry. The average healthy and mature almond tree can produce a tree-mendous 50 to 65 pounds (23 to 30 kilograms) of nuts.

Pests and Diseases

Almonds, as I’ve already mentioned, are sensitive souls. They therefore may suffer from a number of afflictions. They are particularly susceptible to soil-borne diseases, such as the fungal disease Verticillium wilt. This causes all kinds of drama for growers around the world every year, and enormous economic damage for commercial growers. Verticillium wilt can be avoided by using a grafted specimen with a hardy root stock of peach or bitter almond. It’s also important not to over irrigate, which encourages the kind of conditions that verticillium thrives in. Soaker hoses are your best bet. Fungal infections can also cause hull rot and there are mitigation techniques for this condition. Apart from that, these trees often suffer from the bacterial disease known as crown gall. This usually gets into the tree via cuts, so care should be taken not to damage the tree. If pruning, always cut branches with clean, disinfected equipment. Almonds may also have issues with mites, such as the brown mite and the red European mite, which stress the tree out and cause damage to its leaves. If using an IPM program in your garden, these mites are best controlled with an oil spray during the trees’ dormant period, or through introducing natural predators such as the Western predatory mite. There are also some pesticides which are effective against mites, including some pyrethroids. Overall, despite being a bit finicky, almonds are definitely worth a shot in your garden. With a bit of light, warmth, and TLC, this can be a beautiful and rewarding tree to have in your back garden. Nuts about nuts? For further reading, check out the following articles:

Death by Black Walnut: The Facts on Juglone ToxicityWith a Bit of Patience, Here’s How You Can Yield Masses of PecansHow to Grow and Care for a Macadamia Nut Tree