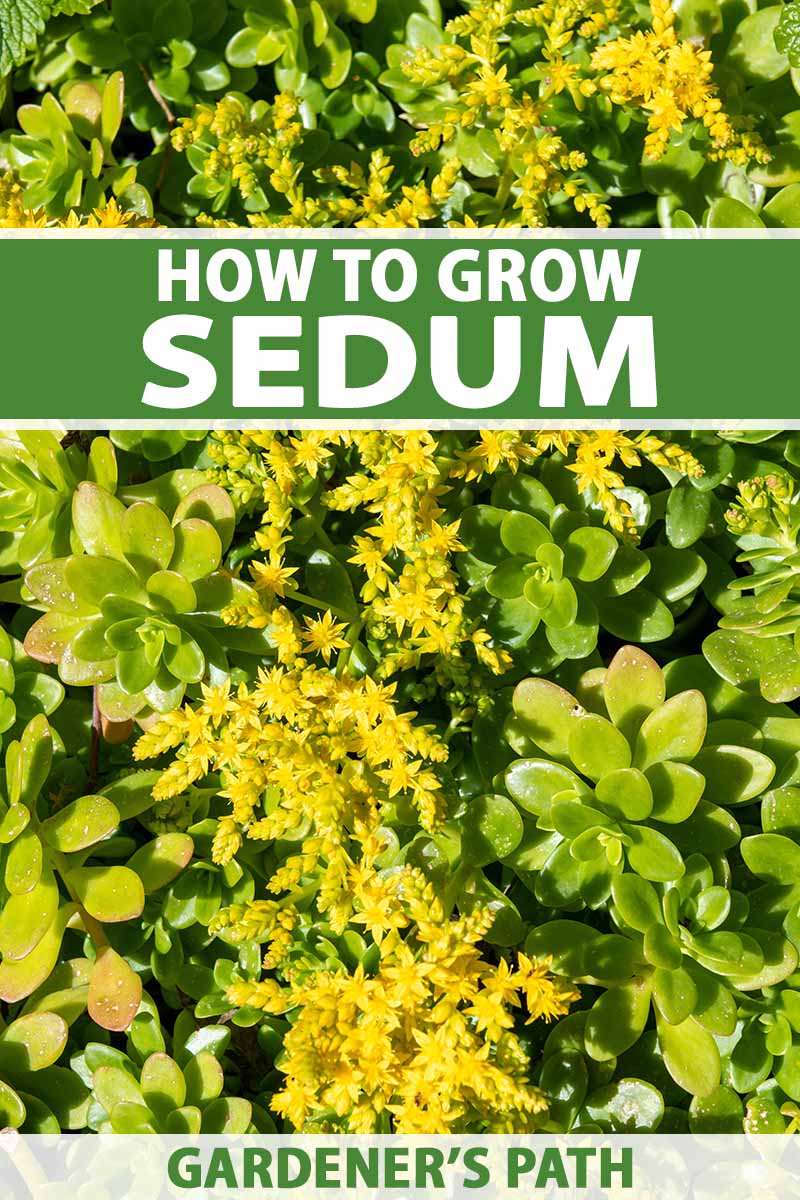

And over time, my eyes built up a visual immunity to them, like my taste buds did with honeycrisp apples. I can objectively say they’re great, but I don’t get that magical feeling of “WOW!” anymore, sadly. So whenever I run into sedum plantings in the landscape, I feel like a kid finding an Easter egg in the yard: I get super excited and wonder if there’s more nearby. Landscape succulents are an exciting novelty for me, and when it comes to stonecrop, an aesthetic mass or mat of it in someone’s garden is a breath of fresh air. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Aside from that and sedum, the only places in Missouri I could reliably find cultivated succulents were bathrooms. A breath of… less-than-fresh air, to be frank. Stonecrop has fleshy leaves and thick stems for conserving water in hot, dry climates. Its blooms are typically star-shaped and they come in many colors, depending on the species. A very versatile genus, Sedum includes both upright and creeping varieties and comes in annual, biennial, and perennial forms. This plant performs as beautifully as it looks: it’ll withstand heat, drought, and foot traffic. It’ll grow in rocky or gravelly soils, and infertile soil won’t be a deterrent. And believe it or not, stonecrop is actually cold-tolerant, as well! If all that sounds appealing, then read on to find out how to grow and take care of these wonderful plants for yourself. Here’s what I’ll cover:

Cultivation and History

Stonecrop can be grown in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 10, but the exact range of zones depends on the species. As a genus, Sedum originates from the temperate zones and tropical mountains of Asia, Europe, Northern Africa, and North America. Stonecrop’s common name comes from its natural tendency to “crop up” in rocky areas. The genus name Sedum comes from the Latin term sedeo, meaning “to sit.” This references the sitting and sprawling nature of stonecrop as it clambers over stones. Sedum nomenclature has a history of instability. A new genus, Hylotelephium, was proposed in 1977 as a way of differentiating upright stonecrop from its low-growing brethren. Hands-in-the-dirt horticulturalists are a bit slower to accept name changes than botanical taxonomists, though, so don’t be surprised if you find some inconsistent genera naming in your upright sedum research. Confusingly enough, upright stonecrops are now taxonomically back with the rest of the sedums… at least in some gardening circles. S. sarmentosum has been used in Asia as a folk medicinal treatment for viral hepatitis and other chronic inflammatory diseases, and many cultures worldwide use some species of stonecrop as a tasty ingredient in soups and salads. Additionally, S. alfredii takes up cadmium and zinc from the soil into its shoots, which makes it a viable option for botanically extracting heavy metals from polluted land and reducing these to nontoxic levels. And it goes without saying that people value stonecrop in the landscape as a versatile ornamental planting.

Propagation

You’ve got a few options when it comes to propagating sedum: seeds, cuttings, division, or transplants. Despite the satisfaction of growing from seed, sown stonecrop seeds don’t always grow true. The non-seed options are a surefire way to end up with the variety of sedum you want.

From Seed

Sowing stonecrop seeds should happen in spring or summer. The minimum temperature necessary for sowing is about 60°F. Select a pot or a seed tray, whichever you prefer. Fill it with a well-draining substrate such as a mix of three parts gardening soil, three parts sand, and one part perlite. A potting mix suitable for cacti works too, if you want to skip making your own. Moisten the soil, spread the sedum seeds over the soil surface, and add a very thin layer of vermiculite on top. Lightly spray it all with additional water. Cover the container with glass, white paper, or a clear plastic bag. Place in an indoor location such as a windowsill to expose it to indirect light for two to three weeks until seedlings appear, and then remove the cover. Keep the medium moist via misting. After six to eight weeks, once outside conditions are acceptable, gradually acclimate the seedlings to direct sunlight outdoors. Start with a half hour to an hour of being in the sun, then bring the container back inside. Increase the exposure time by 30 to 60 minutes every day until the seedlings are conditioned for the time they’ll be spending in the sun after transplanting. At this point, you’ll want to permanently move them into their new location. Make sure to use sterile tools and materials in doing so.

From Cuttings

Before preparing your cuttings, you’ll want to choose a container such as a tray or pot. Fill it with a similar medium to what you might use for growing stonecrop seeds as described above. To take a cutting from stonecrop, cut three to six inches of stem from a healthy plant in early spring. Remove the bottomost leaves and stick the cut end in the growing medium. The cutting doesn’t have to be upright, it can lie prone as long as the end of the cutting is making contact with the soil. Mist the medium with water, and keep it moist until the cuttings develop roots, a process which should take six to eight weeks. When you start to feel a cutting resist when you pull on it, then you know that it’s developed adequately-strengthened roots. Wait another week or two before you harden them off as described above.

Via Division

To divide stonecrop, select a mature plant in the spring or fall and dig it up, being careful not to damage the roots. Take the mass of roots and gently tease or cut it apart into the desired number of divisions, ensuring that each root clump has aboveground growth attached. At this point, each daughter sedum is ready for transplanting.

Via Transplanting

The ideal timing for transplanting is the beginning of spring or just prior to it, when plants are primed for new growth. Transplanting sedums is pretty simple: dig a hole wide enough and deep enough so the root ball can fit with some room to spare in the hole, with the top of the roots positioned just below the soil line. Place the plant in the hole, fill in the gaps with the surrounding soil, and pat it all down firmly. Water in the transplant, and voila! For multiple transplants, you’ll want to space them out anywhere from six inches to two feet apart. Err on the side of less space for low-growing types, and more space for the upright ones.

How to Grow

Now that you’ve got some sedum ready, let’s explore how to grow it. Since this is a general sedum growing guide, these directions will be a bit cookie-cutter. Some supplemental research on your choice of stonecrop species will help you find the optimal growing conditions, but for now, the following recommendations will serve you well.

Climate and Exposure Needs

Various species of Sedum are distributed worldwide, and are able to grow in many different temperature ranges. As a genus, these plants will generally grow in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 10, but the exact zones vary between species. Stonecrop doesn’t like excess humidity or wetness. Given sedum’s tolerance for heat and dry soil, err on the side of warm and dry over cool and humid. But stonecrop is tough, and it will make do in less-than-ideal conditions. These plants grow in full or partial sun, but as a general rule, full sun – or at least six hours of direct sunlight per day – results in better growth. If your garden’s patches of full sun exposure are limited, partial sun will do. Just know that the more low-growing and vigorous the sedum species, the more shade it can tolerate before growing floppily, and vice versa.

Soil Needs

Sedums prefer lean, well-draining, coarsely-textured soil. This is best achieved with coarse sand, but gravel-heavy soils will work in a pinch. The ideal pH for these plants is slightly acidic to neutral, or 6.0 to 7.0. Deviating from the above recommendations will most likely lead to problems. Too much moisture retention can cause rotting, and a soil that’s too high in nutrients can cause leggy growth. The latter isn’t a huge issue for low-growing species, but upright varieties of stonecrop can become top-heavy and flop upon flowering if the soil is rich enough.

Water and Fertilizer Needs

Supplemental stonecrop irrigation is only necessary for established plants when the top two inches of soil is dry. You won’t have to water that much… and depending on rain, you might not have to water at all! Sedum is pretty drought-resistant thanks to its succulent leaves. Since stonecrop does well in nutrient-deficient soil, supplemental fertilizer isn’t necessary. It bears repeating: too much nutrition results in weak and leggy growth. If you absolutely must fertilize, working an inch of compost at most into the soil annually is more than enough.

Growing Tips

Direct sun is ideal, but partial sun is acceptable for low-growing species.Grow sedum in lean, well-drained, coarse soils.Supplemental fertilizer isn’t necessary.Only water when the top two inches of the soil is dry.

Maintenance

Sedums are pretty low-maintenance, but there are some things you can do to keep them looking their best. Pinching living flower heads before they fade or topple will strengthen the stems, if you’re working with less-than-ideal conditions that could result in flopped-over stonecrop. In addition, pinching spent blooms will help clean up the plants a bit. But it’s not necessary, since the dry flower heads will provide winter interest if left alone. Here’s a neat trick you can do with your upright stonecrop: select a few specimens in your garden when they’re eight inches tall and cut them down by a third. This will result in later blossoms and an extended blooming period overall! The only effort low-growing species need by way of maintenance is the occasional pruning if they go out of bounds and encroach on other plantings. Be sure to dispose of your clippings properly: if you just leave them in the garden or chuck ‘em into random plantings, you could get sedums popping up where you don’t want them to. Debris left in the garden can also encourage pests and disease pathogens.

Species to Select

The Sedum genus consists of 600 or so total species – and that’s a gargantuan amount of stonecrop! You can narrow the list down by deciding between upright and low-growing varieties, but even that leaves a lot of options. Let’s go over some superior sedums.

Deer

Luckily, sedums are somewhat resistant to deer, thanks to their bitter taste. But when deer start running out of food in wintertime, poor flavor won’t deter them from taking some desperate nibbles. It’s topped with showy clumps of red, pink, or white flowers, and a group of ‘em automatically grows into a rounded shape, no pruning required. As an upright species, it reaches 18 to 24 inches in height, which fits in nicely with the rest of your perennial garden. For optimal growth, cultivate this type of sedum in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 10. There are some beautiful varieties available besides the standard species. ‘Brilliant’ is a premium showy stonecrop cultivar with bright pink flowers, while S. spectabile var. atropurpurea has deeply purple foliage. ‘Autumn Joy’ is a hybrid between S. spectabile and S. telephium, and its stunning year-round interest makes it one of the best garden perennials. ‘Autumn Joy’ Individual, four-pack, or 10-pack gallon-size containers of ‘Autumn Joy’ are available from Fast Growing Trees.

Two-Row Stonecrop

S. spurium is a low-growing species that tolerates urban conditions remarkably well. Reaching four inches in height – six when flowering – this plant spreads as a dense mat in the landscape. It looks amazing as both a ground cover and a complementary patch of growth between other plants. This plant has paddle-shaped leaves and rounded toothing on the margins. Pinkish-red flowers protrude beyond the foliage. This stonecrop species thrives in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 8. Notable cultivars include ‘Bronze Carpet,’ with reddish-bronze foliage and pink flowers, as well as ‘Fuldaglut’, which has scarlet flowers and deep red foliage. ‘Fuldaglut’ You can acquire ‘Fuldaglut’ from Nature Hills Nursery. This species can become invasive in certain zones if it’s not closely monitored.

Orange Stonecrop

S. kamtschaticum is an evergreen sedum that performs well on hillsides, within pockets in stone walls, and along borders, providing visual interest in these spaces. Growing best in Zones 3 to 8, its light green leaves are long, skinny, and toothed on the ends. Flowers are yellow to start, but produce orange seed heads with age, hence the common name. A cultivar worth mentioning is ‘Variegatum,’ which has many cool features. Its foliage is variegated, with white leaf margins that are flushed with pink. The flowers are also a bit different: they’re a deeper, more intense yellow than those of your everyday orange stonecrop. Orange Stonecrop Nature Hills Nursery has orange stonecrop plants available for purchase.

Managing Pests and Disease

As a group, these are pretty tough plants. But that doesn’t mean they’re invincible. Let’s analyze some potential threats to a sedum’s health.

Herbivores

Humans aren’t the only mammals that find stonecrop tasty. Woodland creatures will also have at your sedum, if given the chance. You might be able to protect clumps of upright stonecrop with caging or netting, but for low-growing types that take up a lot of square footage, forget it. You’re better off enclosing your garden as a whole, which will also protect your other plants that deer could snack on. Read about DIY deer fencing in our guide. Using deer repellent sprays will be less visually obtrusive, although rainfall may necessitate repeat applications.

Rodents

Squirrels and voles will eat sedum, too. For these pests, caging and netting are worthwhile options. They won’t have to be as tall as the kind you’d use for deer, but they’ll have to be unclimbable and sunk a few inches deep below the surface of the soil so that rodents can’t tunnel their way in. Rodent sprays can be applied to the plants directly, while rodent-repellent pellets can be applied to nearby soil surfaces and watered in so the roots are protected from subterranean pests.

Insects

Insects go hand in hand with disease, since they can also be vectors for pathogens. Properly protecting your stonecrop against insects will go a long way in warding off disease, too.

Black Vine Weevil

Also known as Otiorhynchus sulcatus, mature black vine weevils are half an inch in length, with a bead-shaped thorax and yellow-haired wing covers.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs are small, white to gray, segmented insects that feed on sap from leaf and stem tissues, which stresses and weakens your sedums. They excrete honeydew and leave behind wispy white clumps of wax on plants, which indicate their presence. Insect pathogenic nematodes can be applied to the soil to control the larvae. Beneficial Nematodes Some high-quality species suited to this purpose, such as Steinernema kraussei and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, are available from Arbico Organics. Foliar sprays of fluvalinate and/or acephate are solid options for dealing with the adults, and they should be applied when the adults are feeding, prior to laying eggs. Timing these sprays every three weeks in May, June, and July should be sufficient. Check your area’s pesticide regulations before acquiring these chemicals. If you can legally use them, refer to the label to ensure safe usage. That, plus the accumulation of egg sacs and the mealybugs themselves, leave the stonecrop looking infested and unaesthetic. Mealybugs can be removed by hand, blasted off with high-pressure bursts of water from the hose, or desiccated by dabbing a 70 percent solution of rubbing alcohol in water on the pests with a cotton swab. Neem oil or insecticidal soaps work too, and if biological control sounds appealing, then introducing ladybugs will help reduce mealybug populations. Learn more about managing mealybug infestations in our guide.

Scale

Scale are itty-bitty insects that suck the sap out of plant tissues, in a similar manner to mealybugs. Control is also similar to what you might do with mealybugs: manual removal, water sprays, isopropyl alcohol, insecticidal soap or neem oil, and/or the introduction of predatory beneficial insects such as ladybugs are all valid means of scale control. Want to learn more about scale insects? We’ve got a guide for that too!

Slugs and Snails

Slugs and snails are both mollusks that share many similarities, except snails have shells while slugs do not. They’re most active on cloudy or foggy days and at night, and oftentimes the only evidence of their presence will be slime trails and damaged plants. Snails and slugs actually prefer succulent foliage compared to other kinds, and will leave behind irregular holes in the leaves and clipped plant parts. Picking out slugs and snails with a gloved hand is effective for controlling these pests. If they seem to be deep in hiding, water the infested areas in the late afternoon. This will draw them out at night, which will allow a flashlight-equipped gardener to pick up and dispose of them in the trash.

Disease

As with insect infestations, unhealthy plants are more prone to succumbing to disease. In addition to properly cultivating your stonecrop, keeping garden tools sterilized and disposing of plant detritus will help prevent a lot of unnecessary infections.

Gray Mold

This disease is caused by the fungus Botrytis cinerea. It tends to show up on dead or dying plant parts as a fuzzy gray mold, which will cause blight if it gets into healthy stem and leaf tissue. Cool and wet conditions are conducive to this disease, along with dead plant tissue like flower heads. Pinching spent blooms will help to prevent infection. Fungicides can be used whenever symptoms start to show up. Thiophanate-methyl is an effective compound.

Leaf Spots

A multitude of fungal species can cause leaf spots: Cercospora, Colletotrichum, or Septoria. The symptoms are strongly defined necrotic patches on foliage, which could cause systemic problems if there are lots of them, and/or they start to merge into larger spots. Fungicidal compounds such as thiophanate-methyl and sulfur will be useful applications in controlling leaf spots.

Powdery Mildew

Caused by the fungus Erysiphe, powdery mildew shows up on foliage as a medley of mycelium and spores. High humidity can allow spores to germinate sans water. Powdery mildew results in overall weakened plants, thanks to the fungal parasite absorbing food from the host into itself. Wiping off the mycelium with a wet cloth can abate the symptoms, but true control can be achieved with fungicides. Acceptable fungicidal compounds include thiophanate-methyl, potassium bicarbonate, sulfur, or triadimefon.

Root Rot

The causal fungi for root rot are Rhizoctonia solani or Fusarium. Symptoms include root systems and basal stems that become blackened or browned, rotted, and eventually collapsed. At the soil line, sunken-in lesions could also occur. Unfortunately, the available fungicides won’t do the trick like they will for the other diseases described above: they’re ineffective against root rot. All you can do for infected plants is remove and dispose of them.

Rust

Rust is a disease caused by Puccinia fungi, and it results in rust-shaded spores and small raised spots on stems or leaves. The surrounding tissues become chlorotic and otherwise discolored, and all of the above results in stunted plants. Fungicides such as mancozeb and sulfur will help control rust.

Stem Rot

A condition resulting in lower leaf chlorosis, total plant necrosis, and eventual plant death, stem rot’s causal fungus is Sclerotium rolfsii. Another identifying symptom is a white growth of cottony mycelium that surrounds the crown at the soil line, which may contain very small sclerotia. Sterilization is the best form of control here: you’ll have to remove and destroy any infected plants in your garden. Sterilizing the infected soil is essential before you plant there again. To do this, lay down transparent plastic over the area for four to six weeks. This will effectively cook the soil-borne fungi to death.

Best Uses

Sedum’s durability and versatility makes it an ideal planting for a variety of ornamental gardening scenarios. Upright stonecrop species will shine as specimens or mass plantings in perennial gardens, while low-growing sedum looks aesthetically awesome as a border, ground cover or filler between your other specimen plants. In general, stonecrop does well on hills, in gravel or rock gardens, and in the crevices of stone walls. Thanks to sedum’s durability against foot traffic, it’ll survive in the highly trodden-upon areas of your garden. Plus, sedum makes a great material for green roofing, if you’re into that sort of thing. Also, stonecrop utilizes Crassulacean acid metabolism, which allows the plant to undergo photosynthesis during the day, but exchange gasses nocturnally. This allows the stomata to remain closed while it’s hot and sunny out, which prevents severe moisture loss in arid climates. An academic understanding of this process isn’t required for enjoying your sedum, but explaining how the CAM plants in your backyard work will make you the star of your patio cookout. Hopefully this growing guide provides a solid base of knowledge in your quest to grow sedum for yourself. But since this was a general stonecrop growing guide, don’t be afraid to deviate from it in order to better accommodate the particular species you’re working with. Have questions? Comments? Put ‘em in the comments section below. I’d love to read them and get back to you! If succulents intrigue you, than pique that interest further with these articles:

How to Grow and Care for SucculentsPropagating Succulents in 5 Easy Steps11 Best Easy-Care Exotic Succulents to Grow at Home