While most of the news concerns California’s $2.5 billion citrus industry, what about beloved trees in family yards? Some of these have been passed down through generations and date to the 1800s. As of 2016, there were between 10 and 20 million residential citrus trees in California. In fact, more than 60% of homeowners in the state have at least one citrus tree in their yard. Citrus greening has yet to infect commercial groves. As of late May 2019, it has only been found on residential properties. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Even a 20% reduction in the amount of land that citrus is grown on in California would result in 7,350 lost jobs and a half billion dollar reduction in the state’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The fate of your trees will likely depend on what part of California you live in. We at Gardener’s Path will tell you what to expect as your trees face this imminent threat, with steps that can be taken to prevent its spread. Here’s what’s to come in this article:

A Two-Pronged Attack

As the saying goes, it takes two to tango. The threat from citrus greening comes from the combination of a foreign insect that infests citrus trees, and the bacteria it can carry that cause the disease. Neither of these organisms can hurt pets or people. They are only a threat to citrus.

First comes the insect – an aphid-sized pest known as the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP) that hails (not surprisingly) from Asia. Not every insect carries the bacteria, HLB (short for Huanglongbing) which is known officially as Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus. As of the time of this writing, 28 counties in California currently have ACP infestations, so there are strict limitations on what citrus can be brought into these areas. The presence of ACP can mean that HLB is not far behind, so agricultural specialists and the state of California take it very seriously if your tree has an ACP infestation. At the moment, there is no cure for this disease. The fruit on infected trees will start tasting bitter, and the tree will decline until it dies – spreading HLB to other trees in the process.

What Areas of California Face the Greatest Threat?

The first case of HLB in California was identified in 2012 in a pomelo in a yard in Hacienda Heights, California, located in Los Angeles County. The next infected tree wasn’t identified until 2015. In 2019, the disease has spread in Los Angeles County, and into Orange County and Riverside County as well. There are two sets of quarantines – one for the insect, and a more stringent one for the disease. At the time of this writing, all of Los Angeles County and part of Orange County are under quarantine because of the ACP, as is part of Riverside County. The quarantine that was established on April 17, 2019, extends from Inglewood and Torrance in the west, north to Arcadia and Glenora, and south to Costa Mesa and Huntington Beach. What does this mean for you if you live in a quarantine area? Your fruit is safe to eat, but you shouldn’t sell it or give it away to anyone who lives in another area. And absolutely don’t move any tree parts like cuttings out of your area. Since HLB will not spread without the ACP, knowledge of the whereabouts of these insects is crucial to containing the spread of citrus greening. The risk is the greatest in climates where citrus trees frequently grow new leaves, which favor ACP breeding and feeding. This means that the Inland Empire and coastal districts of Southern California are prime feeding grounds for ACP. Fortunately for growers in the San Joaquin Valley, the hot, dry weather doesn’t favor the insects. Growers in this area have been able to keep ACP populations below detectable levels for most of the year.

How to Look for ACP or HLB

Inspecting your trees might be a bit more involved than you think, since homeowners often don’t realize that other plants in the Rutaceae family can harbor the psyllids. Examples include wampee and Murraya species, such as orange jasmine, mock orange, and curry leaf trees. All of these plants can serve as hosts for the psyllid, as well as all members of the citrus genus.

The Insect

You should check your trees for psyllids each month. This is particularly crucial when you see leaf flush, or tiny new leaves growing. You will have trouble observing the adult psyllids because they fly, and their eggs are tiny. Your best bet is to look for the nymphs. They stay on the new leaves, don’t move much, and most importantly, they produce waxy white tubules that look unique.

The Disease

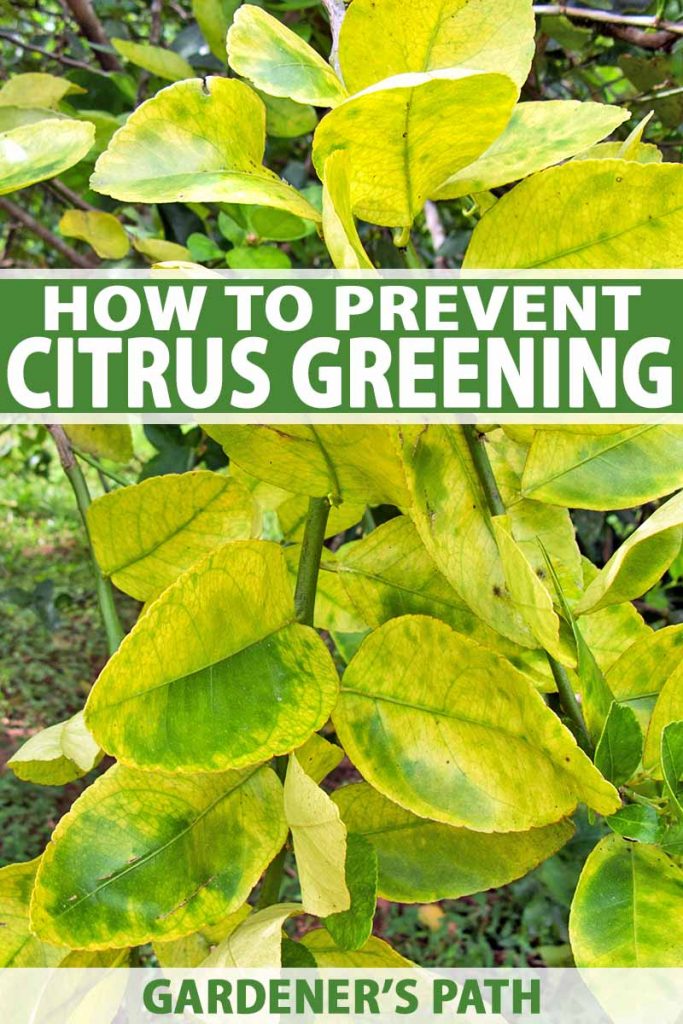

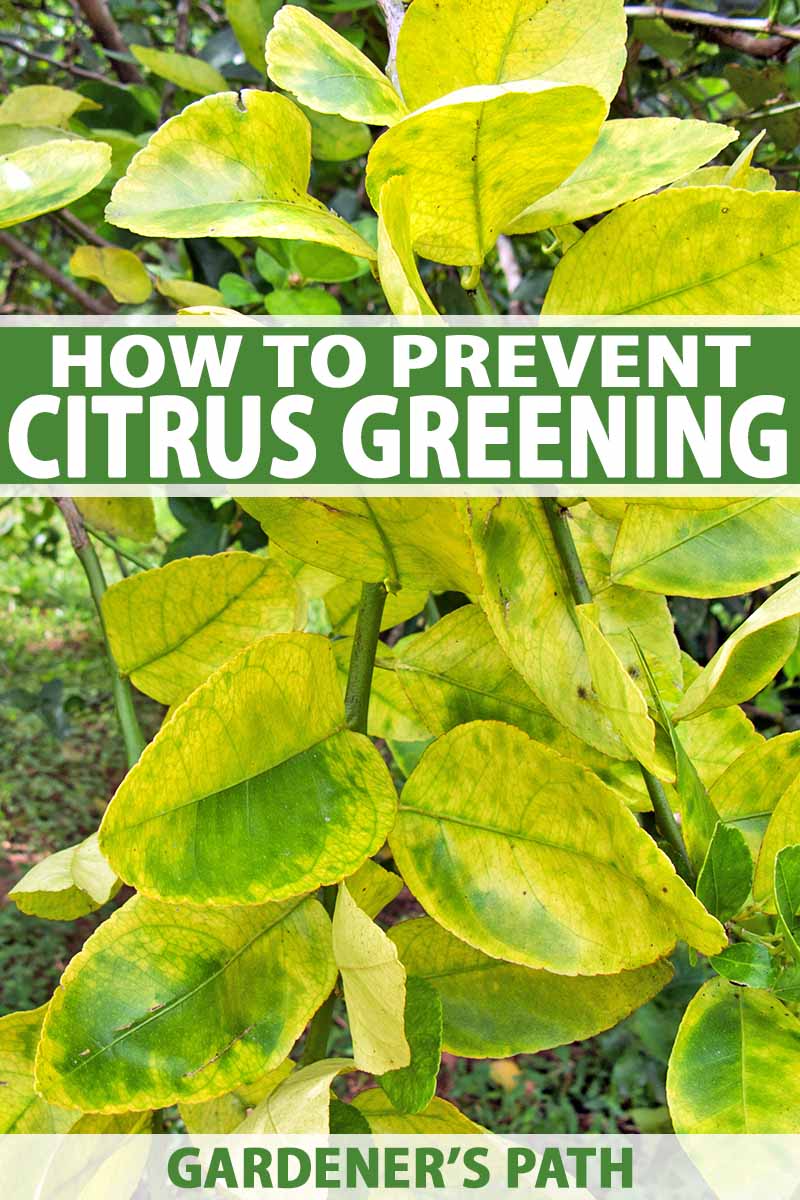

Yellowed leaves are the first and most important symptom. However, citrus often has yellowed leaves because of nutrient deficiencies. You can tell the difference because leaves that are yellow due to a nutrient deficiency have a similar pattern of yellowing on both sides of the leaf.

In contrast, HLB causes blotchy yellow mottling that varies from one side to the other. This appearance is why HLB translates directly to “yellow dragon disease.” Another indicator that the disease is due to HLB is that the veins may be corky.

What to Do if You Find ACP or HLB

The Insect

If you find an ACP on your citrus, your first step should be to check the up-to-date map of where the insects have been found in your area. The site that hosts this map is the state’s official repository of information on the spread of ACP and HLB in California. It is managed by the Division of Agriculture & Natural Resources of the University of California.

What you do next will depend on where you live in California. If you live in the northern or central part of the state where the insect is rare, immediately call the Pest Hotline at the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) at this number: 1-800-491-1899. Experts will come to your house to verify that the insect in question is indeed an ACP, and they will also treat your citrus trees to eliminate the insect in your area. If you are in Southern California, ACPs are well established. You should treat your trees yourself, or call a licensed pesticide applicator.

The Disease

If you think your tree is infected, call the CDFA Pest Hotline number or your local agricultural commissioner’s office ASAP. An expert will come out and take a leaf sample to determine if it is infected with the bacteria. You should closely monitor the spread of HLB. Check the current map of psyllids, HLB, and parasites to see how close HLB is to your property. You should consider replacing your citrus tree with a non-citrus one if the disease has been found in or near your neighborhood. If this is the case, your tree is probably already infected. The problem is that it can take a long time to diagnose this disease, and ACPs could be spreading the disease without your knowledge.

What to Expect During an Inspection

1. Notification and ACP Sampling

This is nothing to be feared and will only happen if ACPs or the disease are found in your area, or local citrus growers are treating their crops.

California Department of Food and Agriculture representatives will knock on your door to let you know that they plan to inspect the citrus trees on your property. They will have a badge and uniform and will NOT ask to enter your home. They may leave a notice if you are not home, and they may place a sticky trap on your tree with a yellow ID card. They may also inspect your tree to look for ACP or HLB if you are not at home. If they see this insect, they may take samples back to lab to test for the disease.

2. Treatment

If your tree needs treatment, you will be invited to attend a public informational meeting. There, you can get your questions answered by the experts. Treatment happens in three cases: You do not need to be present for the treatment, although the highly trained specialists will be happy to schedule a time if you have a specific request. If you are not home, they will apply insecticides safely and only to the citrus tree. There are two ways of spraying: Once the treatment has been completed, the specialists will leave you a notice to confirm this.

3. Disease Testing

Samples will be sent to a lab to look for HLB. The lab uses rigorous tests that meet federal standards. You will be notified immediately if your tree tests positive for HLB. Unfortunately, this test is not always effective at detecting HLB. The organism isn’t found evenly in all parts of a tree, so it’s easy to miss during the sampling. California officials are currently testing trained dogs that have been 99% effective at detecting HLB in Florida. If they function as well in California, this will greatly speed up detection of the pathogen.

4. Removal

If your tree is infected, it will be removed at no cost to you to prevent the disease from spreading.

Treatment Options for the Asian Citrus Psyllid

These insects are difficult to eradicate! They are easy to kill, but their populations rebound quickly. And they can travel long distances, either by being carried by the wind or by flying. The state of California uses both insecticides and natural predators to treat ACPs. You can either treat the ACPs on your citrus yourself, which has a low to moderate degree of effectiveness, or you can bring in professionals. Their treatments are highly effective against ACPs. You have a choice of classic insecticides or insecticidal soaps, oils, and pyrethrins. Recent research from Florida suggests a combination of organic insecticides and insecticidal soaps and oils.

Biological Control

The State of California favors biological controls in the counties in which ACPs are well established, and that have scattered residential trees in urban centers far from commercial groves. Agricultural officials decided that it would be more cost effective to release natural predators of the Asian citrus psyllids than to spray in these areas. However, finding a natural enemy was not trivial. Such beneficial insects are much more abundant in a place where a pest has evolved. Part of the reason that animals and plants can spread so widely in a new area is that they left their enemies behind!

One dedicated researcher, Mark Hoddle, went to Pakistan to identify potential enemies of the ACP. He identified nine types of insects that showed promise and narrowed his list down to two parasitic wasps that were suitable for California’s climate, and did not pose any detectable threat to native plants and animals. Between 2011 and 2019, more than ten million tiny stingless wasps were raised and released in Southern California, at residential sites ranging from Imperial County to Santa Barbara. The most commonly used wasp is Tamarixia radiata, while Diaphorencyrtis aligarhensis wasps have also been released. While these biological control wasps will not eradicate ACPs, researchers are optimistic that they can help to keep the populations low until an HLB cure is found. One critical thing to keep in mind if your tree is home to these parasitic wasps is that you must keep ants under control. They like to feed on the honeydew produced by the ACP nymphs. And they will eat the parasitic wasps!

Organic Insecticide Treatments

It is important to use soft insecticides, such as oils and soaps, if the parasitic wasps have been released near you. An entomology professor in Florida conducted exciting research on alternatives to conventional insecticides to control ASPs. Dr. Jawwad Qureshi and his colleagues found that alternating organic insecticides with either 435 Oil from PetroCanada or the insecticidal soap M-Pede controlled this pest as well as conventional insecticides over the two-year period of his study.

Conventional Insecticide Treatments

If you want to stick with conventional insecticides, you will need to spray the leaves and treat the soil. Foliar sprays of Sevin or Malathion are moderately effective for the insects and should work for several weeks. One thing to keep in mind if you go this route is that you need to make sure that you are making contact with the insect’s body when you spray. You will also have to treat your tree more frequently than if you were to use conventional insecticides.

Asian Citrus Psyllid Detector Traps, Hangers, and Lures California experts recommend that you check for the insects every two weeks. You can buy sticky traps to target ACPs specifically, available via Arbico Organics. However, these traps will only trap adult psyllids. And another problem is that they are more attracted to the leaves when they are flushing than to the traps. If you find the psyllids, you should spray twice with organic insecticide, leaving a 10 to 14-day interval between applications. This should take care of these pests, but if you find them again, continue spraying every 10-14 days until you don’t find any more of them. A soil drench will permeate through the tree and help control the ACPs. UC experts from the Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources recommend that you use Bayer Advanced Fruit, Citrus & Vegetable Insect Control if you see psyllids in the summer or fall. This treatment should be effective for months. You should not apply insecticides while your tree is in bloom, so you won’t affect any bees. The professionals that you may choose to hire will use more powerful insecticides that are highly effective against the ACP, providing protection for months. They will use the products Tempo and Merit. As is common with insecticides, the insects can develop resistance to these pesticides. This has been a growing problem in Florida where some farmers intensively spray their groves. Since all of the infections found so far as of the time of this writing have been in residential or abandoned trees, homeowners are on the front lines in the battle to keep citrus greening out of the commercial citrus industry in California. You should monitor for ACP and then act in the way that is best for where you live. In Southern California, you should treat your tree, or have it treated or removed. And be sure to report all findings to the appropriate environmental authorities. If the spread of HLB can be minimized, California could continue its nearly $2.5 billion annual production of citrus, while homeowners can keep their beloved citrus trees. Only YOU can prevent HLB from spreading. Are you currently battling Asian citrus psyllids, or have you been able to keep them at bay? Let us know in the comments. For more information on growing citrus fruits, you can get started here. And to learn more about other common diseases and pests that may plague your garden, read more:

How to Battle Colorado Potato Beetles in Your Garden How to Prevent and Control Powdery Mildew on Apple Trees How to Identify, Prevent, and Treat Scab in Stone Fruits

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Insect photos via Wikimedia Commons. Product photo via Arbico Organics. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock