A leafy green superstar in Asian cuisine, bok choy – or pak choi – is quite delectable, whether it’s consumed solo or as an ingredient in a more complex dish. Nutritionally, it’s loaded with vitamins K and C, while the high fiber content of this veggie will definitely save you some strain and struggle on the porcelain throne. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Unfortunately, pak choi can be struck by disease at times, which can render it a sickly and inedible clump of greenery. But by taking the proper precautionary measures and reacting appropriately to any infections, gardeners can transform a potential catastrophe into a mere inconvenience. This guide will go over a handful of disease conditions, along with how to identify, prevent, and combat any ailments that happen to afflict your bok choy. Here are the specific diseases we’ll go over: Besides the specific prescriptions for each of the above conditions, properly cultivating your pak choi and being sanitary with your gardening practices will help to prevent disease. Proper cultivation means caring for the plant in a way that promotes optimal health and vigor, while sanitary gardening practices entail the use of sterilized tools, disease-free soil, and robustly healthy bok choy specimens. For tips on how to cultivate your bok choy correctly, check out our guide. Additionally, managing pests will further prevent disease, since these unwanted visitors can sometimes vector pathogens of their own. For further reading on the subject, this guide covers the ins and outs of bok choy pest management.

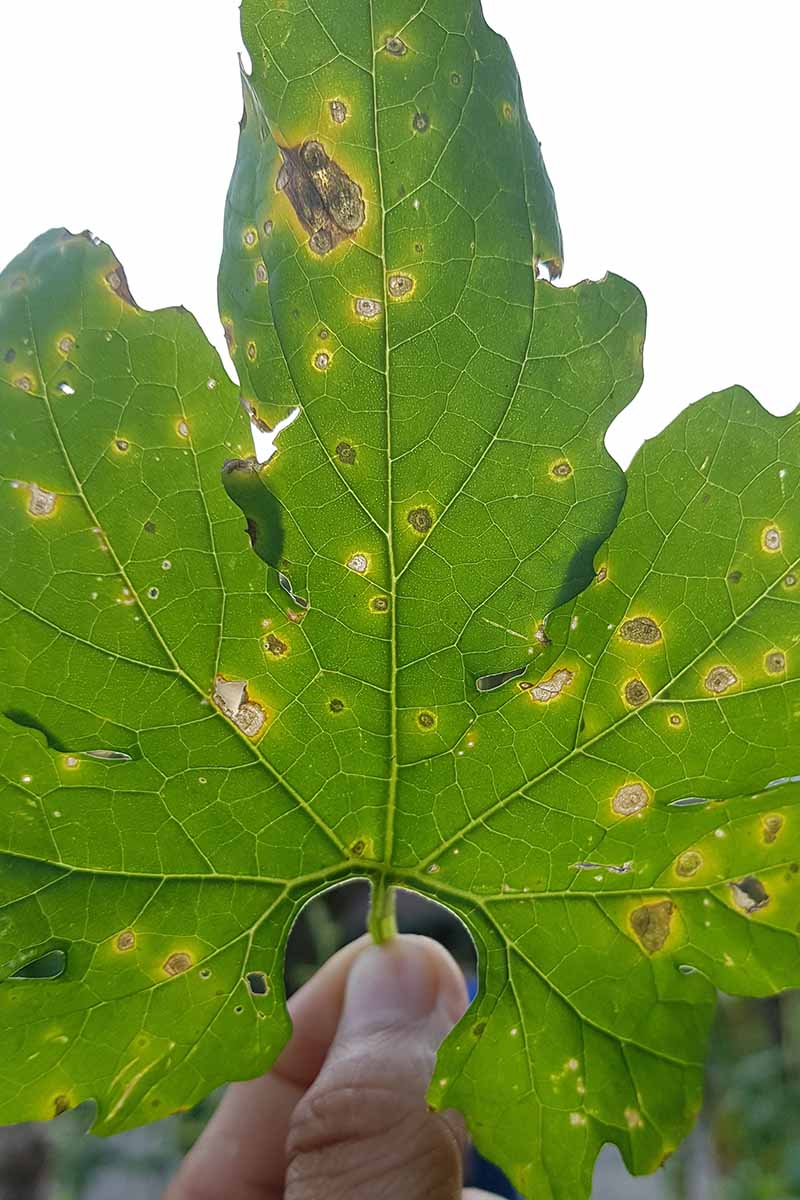

1. Alternaria Leaf Spot

A common affliction of bok choy and other cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and kale, alternaria leaf spot is a fungal disease that also goes by the name “black spot.” The causal pathogen is at least one of three different species of Alternaria: A. brassicae, A. brassicicola, and A. raphani. As fungi, these organisms produce spores that hitch a ride on water, wind, and gardening tools from their overwintering sites, which tend to be the nearby detritus of diseased plants. They can also enter your garden via infected seeds and transplants, which makes the use of disease-free pak choi from the get-go super important. Alternaria leaf spot spreads best in warm and humid conditions, with temperatures of 60 to 78°F and 90 percent relative humidity. Symptoms of infection include brown, rounded spots with concentric rings on the leaves. These spots typically occur on older leaves first, and often have a surrounding chlorotic halo. Over time, the leaf spots can merge into large masses of necrosis, which rapidly deteriorates plant health and severely cripples growth. Besides utilizing Alternaria-free seed and transplants, Alternaria leaf spot can be prevented by removing weeds and plant detritus from your garden, along with leaving three-year intervals between seasons of growing Brassica plants in the same place. Space bok choy plantings at least 10 inches apart, while leaving 18 to 36 inches of space between rows. For the most part, any infected specimens should be removed and destroyed for the good of the entire plot. But if all of your specimens are infected, then feel free to only remove infected foliage for the sake of eventually harvesting whatever healthy bok choy you can salvage.

2. Bacterial Soft Rot

“Bacterial soft rot” refers to a group of bacterial diseases that affect a wide variety of garden edibles from cucurbits to cruciferous veggies. Many different types of bacteria can cause this type of disease, such as Pectobacterium carotovorum, Dickeya dadantii, and particular species of Bacillus, Clostridium, and Pseudomonas. These bacteria tend to enter through plant openings and wounds, and spread via the movement of infected tools, insects, soil, water, and plant debris. Wet conditions and limited oxygen can further accelerate spread, and while bacterial soft rot can occur over a wide range of temperatures, the most severe decay happens in conditions between 70 and 80°F. Symptoms begin as water-soaked spots on foliage that grow over time into larger, cream-colored masses of rotted and mushy tissue. If the surfaces of these masses cracks, out comes a slimy liquid that darkens to a tan, brown, or black color upon exposure to the air. Ultimately, the soft parts of the plant collapse due to cell wall breakdown. Adding insult to injury is the accompanying pungent odor that can only be described as “funky” – and not the catchy, Earth, Wind & Fire kind. You can prevent bacterial soft rot by avoiding excessive irrigation and watering only at the soil line rather than overhead, properly spacing plantings, and rotating pak choi with less susceptible plants such as beets and beans. Clean up any nearby plant debris, and avoid planting in sites that have been previously infected for at least three years. Plants low in nutrients – calcium in particular – can exhibit especially severe symptoms, so ensure that the micronutrition of your plantings is up to par. Once infection occurs, it’s game over. Since there’s no known cure, all you can do is immediately pull and dispose of any afflicted bok choy as soon as possible. Read our guide for more tips on combating bacterial soft rot.

3. Blackleg

Blackleg is caused by Phoma lingam and Leptosphaeria maculans, which are two different life cycle stages of the same fungal pathogen. Although P. lingam utilizes sexual reproduction and L. maculans relies on asexual reproduction, both create fruiting bodies that release spores that may afflict a plethora of Brassica crops. Infected seedlings often incur damping off, while adult plants develop necrotic gray lesions with black or purple borders that are dotted with fruiting bodies that go on to produce more spores. Below the soil, roots can blacken and rot, forming a “blackleg.” Given time, these symptoms often lead to plant wilting and death. Ensure that the soil bed you’re planning to use hasn’t been infected with blackleg in the last four years prior to planting. Remove nearby weeds and volunteer cruciferous plants, and make sure to eliminate nearby plant residue with extreme prejudice. Pull and destroy any infected plants.

4. Black Rot

A particularly nasty disease of cruciferous plantings, black rot is caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, a bacterium that essentially clogs up plant xylem with a mucus-like sugar known as xanthan. Primarily spread via infected seeds and transplants, black rot has the potential to travel very long distances. The causal pathogen also moves by hitching a ride on people, tools, insects, water, and wind. Warm and humid conditions further accelerate the disease, which begins on leaves before moving into the stems and roots. Infected leaf margins start to yellow in an irregular fashion, which progress into large, V-shaped, chlorotic and necrotic patches on the foliage, with the V pointing like an arrow towards the bases of the leaves. This damage can do quite a number on the health of your bok choy. Sanitation is essential: rotating pak choi with non-brassicas every two years, weed management, providing plenty of space between plants, eliminating excess moisture, and making sure the bok choy you’re working with is disease-free from day one. Soaking seeds for half an hour in 122°F water before planting should eliminate any bacteria present. Infected seedlings and plantings must be removed and destroyed as soon as possible, since a single infested specimen can lead to an outbreak in a favorable environment. Further pointers on dealing with black rot can be found in our guide.

5. Clubroot

Named for the swollen “clubs” that form on the roots of infected plants, clubroot occurs as a result of infection by the fungal pathogen Plasmodiophora brassicae, which is thankfully not seed-borne. It does, however, enter the garden via infected transplants or compost. Besides the clubbed roots this illness is known for, infected plants display stunted growth and wilting, along with possible leaf chlorosis. These symptoms are enough to kill juvenile plants, while afflicted older plants will simply fail to yield anything harvestable. Either way, infected pak choi should be pulled as soon as symptoms are discovered. You can avoid the risk of clubroot by growing bok choy from seed, along with utilizing disease- and symptom-free transplants. Don’t use compost that you aren’t sure has reached temperatures of at least 148°F during the composting process. Remove weeds and plant detritus to reduce further spread, and avoid planting brassicas in infected garden soil for five to seven years in order to reduce the number of pathogens present.

6. Downy Mildew

Caused by Peronospora parasitica, a water mold or oomycete, downy mildew hits bok choy seedlings particularly hard, but mature specimens might also take a hit from this disease. The causal pathogen overwinters in cover crops or on nearby cruciferous weeds, producing spores that spread via wind and splashing water. Spores that don’t end up infecting living plants may survive in the soil and in nearby organic residues. Preferring cool and most conditions, spores land on pak choi foliage and quickly germinate, producing new reinfections in as little as four to five days. Infected seedlings often die straight away, while afflicted adults develop small dark spots and chlorosis on their foliage. On leaf undersides, a white-gray growth of mildew is especially noticeable on wet leaves. Along with the damage sustained from downy mildew itself, infected bok choy is also susceptible to further attack from other pathogens, all of which leave the plant sickly and unable to yield tasty goodness to their full potential. Rotating pak choi with non-brassicas is important for disease prevention, along with removing nearby overwintering sites such as weeds and plant debris. Irrigating early in the day and properly spacing your bok choy will cut down on that excess moisture that the pathogens love. But above all, fungicides such as chlorothalonil and mancozeb are the most important forms of downy mildew control. Apply according to instructions and local laws. Rotating fungicides is important for keeping pathogens such as Peronospora parasitica from developing fungicide resistance – we share some pointers on doing so in our guide.

7. Rhizoctonia Bottom Rot and Damping Off

Depending on the age of the infected plant, the fungal pathogen Rhizoctonia solani can cause either bottom rot or damping off symptoms. Seedlings and young transplants are susceptible to damping off. The pathogen attacks part of the stem just above the soil, which leads to browning, cracking, and lesion formation on the outer stem surface. Although the xylem is left intact, afflicted plants are stunted, wilted, and turn purple, and the stems of seedlings can often break at the soil line. Bottom rot occurs when Rhizoctonia infects lower pak choi leaves, resulting in oval, dark brown lesions where the soil makes contact with the foliage. These lesions often become soft and watery thanks to secondary decay organisms. The inner head of the bok choy can become exposed as infected foliage wilts. Warm soils make for an ideal planting site, since a warm medium results in faster germination and the growth of more vigorous seedlings. Excessive moisture encourages fungal activity, so keep the soil from becoming too wet. Any plantings with severe symptoms should be promptly removed and destroyed. This is not to say your pak choi is invulnerable. Sometimes crops can still become infected despite your best efforts, but that’s just the name of the game. Every setback in the garden is an opportunity to learn… and there will always be future growing seasons! Questions, random remarks, and personal experiences can go in the comments section below. If this guide further piqued your curiosity about growing bok choy, then follow these articles further down the rabbit hole:

Bok Choy vs. Baby Bok Choy: What’s the Difference?How to Prevent Bok Choy from BoltingTips for Growing Bok Choy in Containers