The promise of gorgeous flowers and carpets of petals, and the delectably tedious art of pruning, makes the headaches over diseases that commonly affect these plants tolerable. At least until the end of fall, that is. Then I give up on them again. But such is the life of the gardener. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. But this comes at the price of requiring lots of attention to detail in terms of plant health and care. If you grow roses, you’re almost guaranteed to encounter disease. Seasoned experts and eager amateurs alike are going to encounter black spot, mosaic, and mildew growing on their roses at one point or another. Let’s take a look at these common and likely problems you’ll discover, and learn how to address them. But first, we’ll go over a few basics on disease prevention. Here’s an overview of what I’ll cover:

Tips for Preventing Disease

Roses want full sun conditions and lots of airflow. They also thrive on being doted on, so regular pruning and removal of dead tissue will help minimize the risk of disease. Hey, roses are a lot like us, aren’t they? Try planting disease-resistant cultivars to start with, to reduce the likelihood of infectious encounters. I have never been a fan of Knock Out® Roses myself, but they are a popular series because they are generally highly resistant to disease.

Chemical Solutions

Always follow the directions on the label of any chemical solution you use in your garden! Too much or too high of a dosage is just as bad, or sometimes many times worse, than applying too small of a dosage. Always refer to the label when using any chemical. On the same note, if you find a strange tip on the internet or in conversation with a fellow gardener, do a little research before following through with it. As much as I’m a fan of old school gardening techniques, I find too much of this is fluffy nonsense.

Keep Those Pruners Clean ‘n’ Sharp

I sharpen my pruners every single morning, and if I’m doing a lot of snipping, I’ll bring the whetstone with me to the jobsite. A sharp blade makes a clean cut, and clean cuts minimize damage to a plant while simultaneously helping to prevent infections. Many rose diseases easily spread to other plants, oftentimes from a gardener’s pruners. I carry a spray bottle filled with rubbing alcohol and spritz my pruners between every plant I prune, or sometimes between every few cuts on the same plant. It’s tedious and annoying, but it’s vital to plant health.

9 Common Diseases

These are some of the more common diseases the home gardener may encounter.

1. Black Spot

One of the most common diseases you’ll find on your plants is black spot. Caused by the fungus Diplocarpon rosae, black spot will defoliate and weaken your roses, making them more vulnerable to other environmental pressures. Think of black spot as a gateway disease; it is unlikely to kill your roses by itself, but it stresses your plants and makes them more susceptible to other infections. This fungal issue is often encountered in the spring and fall, when conditions are wet and cool nights prevent moisture from evaporating. Warm weather over about 80°F (26°C) tends to prevent black spot from occurring in the first place, and dry weather inhibits the progress of this disease. Water splashing on infected leaves is what spreads the fungus, so a lack of precipitation and unnecessary irrigation means minimal spread of infection! Black spot often begins its damage at the base of the plant and works its way to the top. Infected leaves will develop a telling bunch of black spots before the plant drops these leaves. Infected canes will look bruised and take on a black or purple hue, indicating the presence of infection. The fungus overwinters in infected leaves and canes, so if your plants have it one year, it’s likely to make an appearance again in the future.

How to Handle Black Spot

Black spot can be treated with a few different types of sprays. However, this is a very difficult disease to handle once an infection sets in, so early care is vital. This was my first encounter with botrytis blight, an awful and ugly disease that most often attacks tea roses, ruining their blooms. Liquid Copper Fungicide Neem oil can also work, but I tend to avoid it when working with roses to prevent causing harm to beneficial insects.

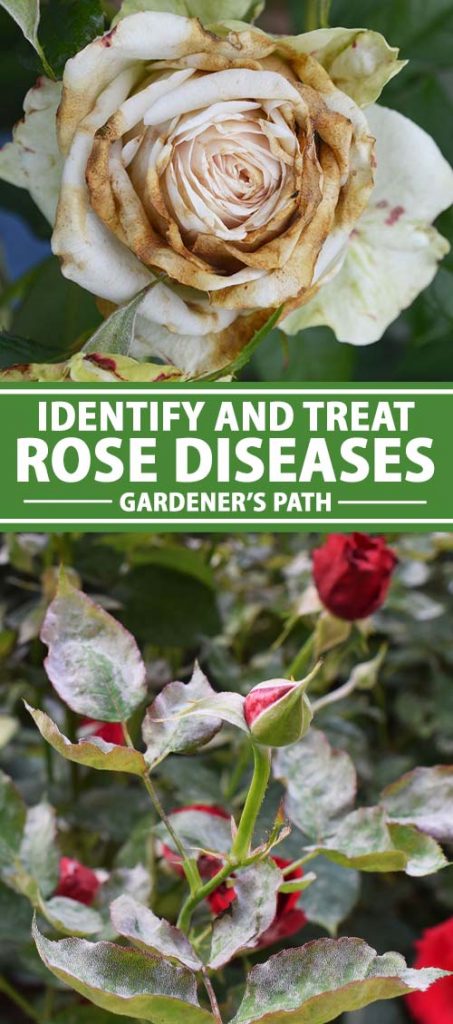

2. Botrytis Blight

I remember watching some tea roses expectantly, eager to see their developing buds blossom into the lovely flowers I’ve come to love (and detest, depending on what time of the year you ask me about it…) then furrowing my brow as the petals turned brown and crispy. Like most fungal infections, this one is caused largely by environmental issues, so a hot and humid summer is the perfect breeding ground for this disease.

Handling Botrytis Blight

While botrytis blight can be controlled temporarily with fungicides, it often adapts a resistance to these sprays which makes them ineffective after prolonged use. Sunny, dry weather is often enough to keep this condition under control. An interesting solution to handling botrytis blight rests in your fertilization practices. Too much nitrogen can create an abundance of new, soft growth that is overly susceptible to this blight. Limit any midsummer feeding you provide to help minimize the risk of blight attacking that new growth.

3. Cankers

This one is an ugly, potentially fatal fungal infection. Canker reveals itself by turning the canes black, most notably in locations where the plant was recently pruned. Always clean your pruners between different plants to prevent this from happening! Interestingly, cankers often cause the most trouble during the colder periods of the year, making them a bit more difficult to notice than other diseases. I’ve encountered them during early springtime pruning, either by discovering old cankers, or noticing new ones taking hold. Roses are susceptible to three types of canker:

- Brown Canker Brown canker is caused by Cryptosporella umbrina. You’ll find tiny, raised, reddish-purple bumps on the canes, a little less than half the size of a grain of rice. As these little spots begin to mature into their fruiting bodies, they develop a brown or black color.

- Brand Canker Caused by Coniothyrium wernsdorffiae, these have a similar reddish color as the brown variety, also found on the canes, but these cankers quickly develop a brown center. I’ve yet to see a brand canker without that brown central coloration.

- Stem Canker Sometimes harder to spot at a glance than the others, stem canker, caused by Paraconiothyrium fuckelii (formerly Coniothyrium fuckelii), tends to have a yellowish color, but it can also swing towards the red slice of the color wheel. This type of canker shows up on the bark.

Handling Cankers

Using clean, sharp pruners, remove the infected tissue and canes. I’ve seen people cut two to three inches below the infected tissue, but I go farther than that if it’s a widespread issue, sometimes removing 75 percent of an infected stem. Cut into the healthy, green area of the plants, and follow up with a fungicidal treatment to give your roses an added boost against reinfection. Make sure you sanitize your tools after each cut. Preventing cankers is surprisingly easy: mulch their roots to prevent the plants from getting too cold in the winter, and make sure you provide adequate amounts of fertilizer.

4. Crown Gall

Crown gall is serious business. It’s also one of the most easily identifiable of all rose diseases. Crown gall is an ugly, weird-looking growth of tissue that looks like a mix between a brain, a praying mantis nest, and a head of cauliflower. It can be a smaller mass of tissue or a larger one, and can occur almost anywhere on the plant, but it almost always develops near the soil level or crown. It is caused by a bacterium (Agrobacterium tumefaciens, for the Latin lovers) that enters wounded tissue. Though it’s easy to identify once you spot it, most of the time, this disease is not noticed until weeks after the date of infection.

Handling Crown Gall

Well, this one is simultaneously easy and sad: remove the infected plant and destroy it, and do not plant another rose in this location for two years. The goal here is to get rid of any residual bacteria in the soil, and any of the original plant’s infected roots, before replanting in that area. Treatments are available to slow the growth of a crown gall and to minimize its damage, but these efforts will not kill this infection. Treatment only slows the progress of the disease and is not recommended.

5. Downy Mildew

Caused by the water mold (oomycete) Peronospora sparsa, downy mildew commonly shows up during cool, damp weather. Rain, humidity, and temperatures between 59 and 64°F are prime conditions for infection. The pathogen spreads via splashing water and wind, and plants that are overcrowded tend to be most susceptible. At first, you might confuse the symptoms of downy mildew with those of black spot: purple or dark brown lesions on the surface of the leaves, stems, and/or flowers. As the disease progresses, spores will develop on the undersides of the leaves forming a mildew-like covering.

Handling Downy Mildew

Keeping your plants well-spaced and pruned to prevent the build up of moisture and watering at the soil level rather than on the foliage will go a long way to preventing this disease taking hold. If you do find your roses are infected, you can treat them with copper fungicide. Learn more about downy mildew and how to manage it in our guide.

6. Rust

A common problem caused by nine different species of fungi in the Phragmidium genus. At its most benign, rust is an ugly condition. But in the worst cases, it will kill the initial host plant and spread to the others. It’s relatively easy to spot rust on your roses. They’ll often drop leaves, and the condition is obvious with its orange, rust-colored marks that appear on leaves and canes. In the winter, infected canes tend to turn black. Rust overwinters in infected tissue, but it can also find a safe hiding spot on trellises and fences, or just about any place near the host plant where it is offered some protection from the worst of the winter weather. Luckily, this fungal issue is specific to roses, so it should only pose a potential threat to the other Rosa species in your garden. This fungal disease thrives in humid conditions where airflow is minimal or nonexistent. Sounds like every summer day in Philadelphia, if you ask me! Remove fallen leaves every autumn and as an early spring cleanup project to help minimize the spread of this fungal disease. If you’re in the planning stage of your garden design, consider purchasing rust-resistant varieties to dramatically minimize your chances of encountering this annoying problem. If you opt for chemical control, consider using Bayer Advanced Disease Control instead of a combination fungicide and insecticide. Bayer Advanced Disease Control

7. Powdery Mildew

If you’re growing roses, you’ve probably encountered powdery mildew before. It leaves a telltale… well, powdery mildew on the leaves, a gray coating that screams “yuck!” It’s commonly spotted in a variety of plants in the garden, and becomes an almost constant annoyance in late summer and early fall. However, it can also thrive in dry conditions, and that’s what makes powdery mildew such a headache. You just never know when it’s gonna strike. If it’s a minor case of powdery mildew, I tend to let it go unmended, but will pay close attention to infected pants to ensure the disease doesn’t spread. Oftentimes this is an issue that will take care of itself in minor cases. A thorough fall cleanup of all shed leaves is a helpful trick to minimize any recurrences.

Handling Powdery Mildew

Either of the fungicides recommended for the previous fungal issues will help to treat powdery mildew. Make sure you’re spraying all parts of the plant, including the tops and bottoms of leaves, on a regular schedule. Some experts recommend an application every two weeks, but as always, read the label of your purchased chemical for its suggested usage. Find more info on controlling powdery mildew on roses here.

8. Rose Mosaic Virus

Rose mosaic is caused by a number of different viruses that are collectively known as the Rose Mosaic Viral Complex (RMVc). Symptoms generally include discoloration and mottling on the foliage and flowers. As the infection advances, growth may be stunted and plants may fail to bloom. This disease is spread by insects, and a plant may be infected for many years before becoming symptomatic.

Handling RMVc

Unfortunately, there is no effective treatment for rose mosaic. The infection is systemic and pruning away discolored foliage will not help – except, of course, to make your plant look better. In the case of a severe infection, the only thing to do is to dig up and destroy affected plants, and only grow certified disease-free specimens in their place. Check out our guide to learn more about RMVc.

9. Rose Rosette

Also known as witches’-broom, in my opinion, this is the saddest-looking disease a plant could possibly develop. It’s as if the physical traits of witches’-broom were meant to twist and warp a rose just enough that it’s still beautiful, but in a very ugly way. You’ll notice this disease, which is spread by a virus-carrying mite, when you see the telltale bizarrely red growth of the plant. Other early symptoms include deformed and brittle leaves with yellow and red pigmentation. As the disease progresses, the plant develops smaller leaves and vibrant red shoots. You’ll also notice a dramatic increase in the number of thorns on the stems of your roses. They will come to look like something more akin to a wild bramble than your favorite rose. This disease spreads throughout the summer as the mites travel on the wind and infect new plants, laying eggs over a 30-day period.

Handling Rose Rosette

Witches’-broom tends to infect wild roses far more readily than cultivated ones, but anything in the genus Rosa is susceptible. It’s recommended that you plant your specimens as far away from wild roses as you can, to avoid transmission. Prune your roses hard each year (I prune mine on the first decent days of early spring), cutting back as much as 70 percent of last year’s growth. This helps remove any overwintering mites and potentially infected tissue. You can also apply insecticidal soap, but be warned that these chemicals kill almost any insect they come into contact with, including natural predators that feed on the mites. If you’ve got a plant that is infected with witches’-broom, you only have one real option for control: destroy the plant and burn it, or place it into a plastic bag and dump it with the garbage. I’d recommend bagging the plant before removing it, to prevent spreading the mites as you carry it around the yard. You can still plant a new rose in the same location, since the disease is transmitted via mites that do not overwinter in the soil. We go further into identifying and controlling rose rosette here. Still have questions? Please drop us a line in the comments below, or share your own tips and tricks for rose disease management. Check out our pruning guide to brush up on that skill, and if you choose to apply any type of chemicals to your roses, read our pesticide application guide. And to read more about growing roses in your garden, try these guides next:

9 Common Reasons for Deformed Rose Flowers (And How to Fix Them)How to Identify and Correct Iron Deficiency in RosesHow to Train Climbing RosesHow to Plan a Rose Garden