It’s not because of the damage they do to plants, but because their nests look like something straight out of a horror movie. An individual caterpillar is kind of cute, right? Some of them even have markings that look like a happy face. But in a group… ugh! We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. It isn’t just the nests, either. In a large infestation, there can be masses of them crawling down the road and sidewalks. Have you ever stepped on a pile of caterpillars before? Double ugh! But despite what I just said about being thoroughly grossed out by them – surprise! – I’m also going to make a case for why you should potentially just leave them alone. Here’s what we’ll discuss.

What Are Tent Caterpillars?

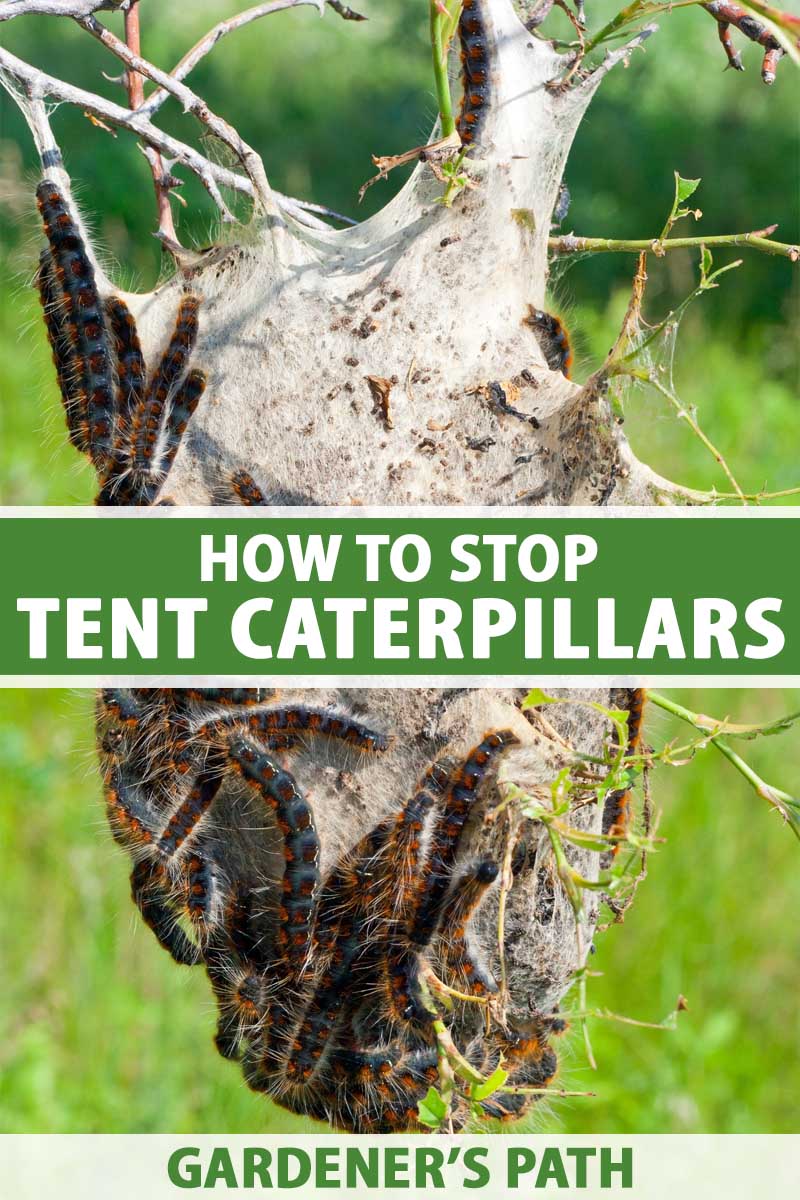

“Tent caterpillar” is a catch-all term that emcompasses the larvae of all types of moths in the Malacosoma genus. Worldwide, there are about 26 species, with six that live in the United States. One thing they all have in common is that the caterpillars create large communal nests made out of silken strands in trees during the spring. Some create a sort of “home base” that they leave and return to during the day, while others create tents continuously as they move throughout the tree. The most common tent caterpillars in the US are M. californicum, also known as the Western tent caterpillar, M. americana, the Eastern tent caterpillar, and M. disstria, or the forest tent caterpillar. M. californicum is found in the western US, southwestern Canada, and northern Mexico. There are several subspecies and they can all vary in appearance. Generally, they have dark blue or black heads, and their bodies are green, black, orange, blue, or a mixture of these colors, with fine hairs (setae) covering their bodies. They always have a line of dots down their backs. They grow up to two inches long. Host trees include aspens, willows, cottonwoods, and mahogany. M. americana lives in the eastern US and southeastern Canada. The larvae are black with a white dorsal stripe and blue dots, and they are covered in fine reddish hairs. Individuals grow up to two inches long. These caterpillars tend to favor fruit trees like cherry, peach, and plum, witch hazel, and hardwoods like ash, birch, hawthorn, maple, oak, and willow. M. disstria is found throughout the continental US and southern Canada. These are brown with pale blue stripes and white keyhole-shaped splotches down their backs. They are covered in fine, light hairs. This species prefers aspens, gums, and oaks, but they’ll make their home in just about any hardwood tree. Unlike the other two mentioned above, this species doesn’t form a home base tent that it stays near. Instead, groups rove throughout trees, forming smaller tents as they go. They might also roll up leaves with silk to form little protective pods. Less common are the Sonoran tent caterpillar (M. tigris), which lives in the western US, and the Southwest tent caterpillar (M. incurva), found in New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and Utah. All tent caterpillars are fuzzy, not smooth, and they lack the large tufts of hair at either end that some other caterpillars have. They also all have either a stripe, multiple stripes, or a broken line of splotches on their bodies. Because they all look different and there isn’t one defining physical characteristic to distinguish them from other caterpillars, it’s easiest to identify tent caterpillars in general by the characteristic tents they make, and the damage they do to trees. The nests they create are made out of silken strands that emerge from their heads, and they are usually formed in the crotches of tree branches. The nests start out small and compact in the spring. As the season progresses, the tents grow in size, and they become more loosely woven as they gradually deteriorate due to wind and rain exposure. They also look creamy white in the beginning of the season, but they gradually take on a brown hue as they fill with excrement. By the way, in case you were picturing a tent made out of silk fabric, their nests are actually more similar in appearance to stacked layers of silken hammocks. These pests are voracious eaters, chewing up foliage as they crawl along the branches of the trees. You’ll notice leaves with ragged edges or defoliated branches at first, followed by the entire tree being defoliated in extreme cases. Interestingly, as the caterpillars crawl around the tree, they leave a silken strand behind them. If one finds a good branch full of big, juicy leaves, it will leave the thread intact so that its fellow larvae can follow the thread to a nice meal. But if it goes down a branch without much to eat on it, the caterpillar will sever the thread so that other caterpillars don’t waste their time looking for food there. In other words, not only do they create communal housing, but they help each other to find food as well. They’re real team players! Sometime in the middle of summer, the caterpillars mature fully and leave the nests to pupate, at which point the silk nests fall apart. Some people group webworms (Hyphantria cunea) into the tent caterpillar category, but they’re different insects. Webworms create a loose nest in the ends of the branches of trees, rather than in the crotch of branches. Webworms are also active in the summer and fall rather than the spring. And finally, to head off any confusion since the larvae of the two are similar in appearance, adult tent caterpillar moths are not gypsy moths. These are Lymantria dispar dispar, another moth species from a different genus altogether.

Biology and Life Cycle

There is only one generation of this pest per year (thank goodness). The eggs are laid in the summer in masses encircling branches, glued in place using a sticky substance they create called spumaline. The masses have a brown hue to them, and the eggs remain in place to overwinter on the tree. The caterpillars hatch in the spring, and they congregate to create a communal nest in a tree where they retreat during the evening and during inclement weather, emerging to feed on the foliage. It takes about six weeks from when they emerge from their eggs to when they head off to form their cocoons on trees, buildings, and fences. As the caterpillars grow, they chomp on the foliage of trees and can even defoliate the entire thing in large enough groups. Once they leave their nests and head out alone to pupate, they stop eating. A few weeks after they form their cocoons, the moths emerge to mate. Most moths of this variety are a dull brown color and have a wingspan of about two inches. The adult moths don’t eat at all. Infestations tend to occur every decade or so, and last for a year or two before the moths move on to other locations, or predators drive the numbers back down.

Organic Control Methods

These days, many experts recommend simply leaving these wigglers alone. Unless the tree is already stressed from disease or other environmental stressors like drought, an infestation won’t kill it. Even if the caterpillars completely defoliate a tree, it should recover after the pests take off. Plus, these insects are an important part of the natural environment and they have lots of natural predators. The larvae and adults serve as a food source for dozens of bird species, bats, lizards, and other critters. That said, there are a few reasons that you’ll want to eliminate these pests. First, if you’re relying on your tree for a harvest, you’ll definitely want to address an infestation unless you’re prepared to go without, or with a smaller than normal yield. That’s because the defoliation can stunt the tree’s growth or output for the duration of the growing season. Because they tend to attack trees that are economically valuable, such as fruit trees, Eastern tent caterpillars are usually the most financially damaging pests in this category, and the ones that you’ll most likely want to control or eradicate. Forest tent caterpillars are a threat to sugar maples, so if you’re growing them, beware. Second, trees that are already stressed from drought, disease, or other pests might not be able to withstand an infestation. If you don’t want to lose your poor tree, you’ll need to give it a little help by removing the pests. Another reason to get an infestation under control is if you have horses. Broodmares can unintentionally eat the caterpillars, and the hair covering the larvae breaks off in their digestive tracts. The hairs then move throughout their bodies, puncturing the intestinal wall and carrying internal bacteria into places where it shouldn’t be. This wreaks havoc that can cause them to abort their foals or give birth to weak foals. And horses that aren’t pregnant can eat the insects and experience eye or heart issues. If eliminating the caterpillars isn’t possible, you might want to move your horses to graze in a different area for a time. Note that the fine hairs on these pests’ bodies have been reported to irritate the skin of some people, and if you, your child, or a pet were to ingest the insects, it’s possible that the hairs could cause issues if they were to penetrate intestinal walls. Finally, if they just plain give you the heebie-jeebies, feel free to remove them. I want to remind you, though, that they are an important food source for many animals and other insects. Their frass, or poop, is also a good source of fertilizer. Plus, there is another benefit to the trees and forest beyond the extra food. After being defoliated, most trees bounce back with more leaves than ever. And while they’re bare, the understory plants receive a big dose of sunlight. So even though I get chills just thinking about them, I choose to let them be in my yard – an intentional technique that scientists call “tolerance.” That doesn’t mean I don’t give them a good, hearty glare when I walk (not too closely) by, however. A final note: If you don’t notice the nests until the early summer, there is no reason to remove them to try and control the pests. At that point, the caterpillars are already mature and they’ll be moving on soon. But if you don’t like the appearance of the webs, feel free to sweep them out.

Physical Control

Your best bet to get a handle on these pests is simply to remove them physically. There are several ways to do this. Trim out the most heavily infested branches, so long as the nest isn’t in a major branch or on part of the trunk. You can also use a broom to sweep out the nests onto a tarp, and then bag and dispose of the bugs. Do the sweeping and pruning at dusk, in the early morning, or during a rainstorm so you can be sure that you’re removing the caterpillars that are at rest or taking shelter as well, not just the nest itself. Do not, under any circumstances, try to torch the nests. They will burst into flame and, as they detach from the tree, they become fiery flags flapping in the branches. Not only is this a serious fire hazard, but it can harm the tree, too. Prune out or remove any egg masses by scraping them off with a knife during the winter. To remove the abandoned nests, use a broom or a strong spray of water from the hose.

Biological Control

These caterpillars have a lot of natural enemies. Put them to work for you to help keep an infestation under control. Beyond encouraging birds to visit your garden, you can also introduce ladybugs, tachinid flies, and parasitic wasps in the Hyposter, Cotesia, and Bracon genera, as well as Edovum puttleri. Spiders, stink bugs, soldier bugs, paper wasps, assassin bugs, and lacewings also eat them. Additionally, most of the damage to the tree is already done once the larvae are near their adult size, so it doesn’t do much good to kill them. Lacewing Adults For instance, Arbico Organics carries lacewing adults and eggs. Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki (Btk) is effective against smaller caterpillars under an inch long, but it’s less effective as they get larger.

Organic Pesticides

To prevent an infestation of caterpillars from occurring in the first place, spray the egg masses in the winter with a dormant oil. This will smother the eggs. Because application timing and the recommended amount varies depending on the plant, follow the manufacturer’s directions closely.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Because this isn’t a pest that typically causes devastating losses, and because there are no pesticides specifically targeted at tent caterpillars available, we don’t recommend using chemical pesticide controls. Monterey Garden Insect Spray Monterey Insect Spray contains spinosad, and you can purchase it in pint, quart, or gallon-size containers at Arbico Organics. Finally, insecticidal soap can be a good organic pesticide to use, but you’ll need to make repeated applications because the soap must come in contact with the larvae to kill them. Make sure to follow the manufacturer’s directions for the specific type of tree you are spraying. Bonide Insecticidal Soap Bonide makes a good ready-to-use option in 12 and 32-ounce containers, which you can purchase at Arbico Organics. To do so could harm the other beneficial insects in your garden, which has long-reaching consequences for the environment. You should also use extreme caution when killing any native insect populations, because this can have an unintended and overall negative impact. They usually won’t kill your plants, they make the birds and other flora in your yard happy, and they can have a positive impact in the garden. Plus, they aren’t too difficult to remove if you just can’t stand them. As far as pests go, you could do a lot worse. If you can practice tolerance, do it. If not, we hope this guide gave you the info you needed to tackle the situation. If so, let us know in the comments. Fellow tent caterpillar nest-aphobes, feel free to chime in so I can feel less alone! And if you’re feeling up to it after your battle against these creepy crawlies, we have some other excellent guides to help you address a pest situation. Give these a read next:

How to Identify and Control Earwigs in the GardenThe Magic of Periodical Cicadas and How to Prevent Garden DamageThe Best Natural Methods to Protect Your Garden From Slugs and Snails