The answer: leaf miner larvae. They’re exactly what their name suggests, tiny immature insects that tunnel between the leaf layers, eating their way through the juicy green photosynthetic bits. If you notice damage to your plants, should you be worried? And if you are concerned, how do you deal with the pests? We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Here’s what we’ll talk about:

What Are Leaf Miners?

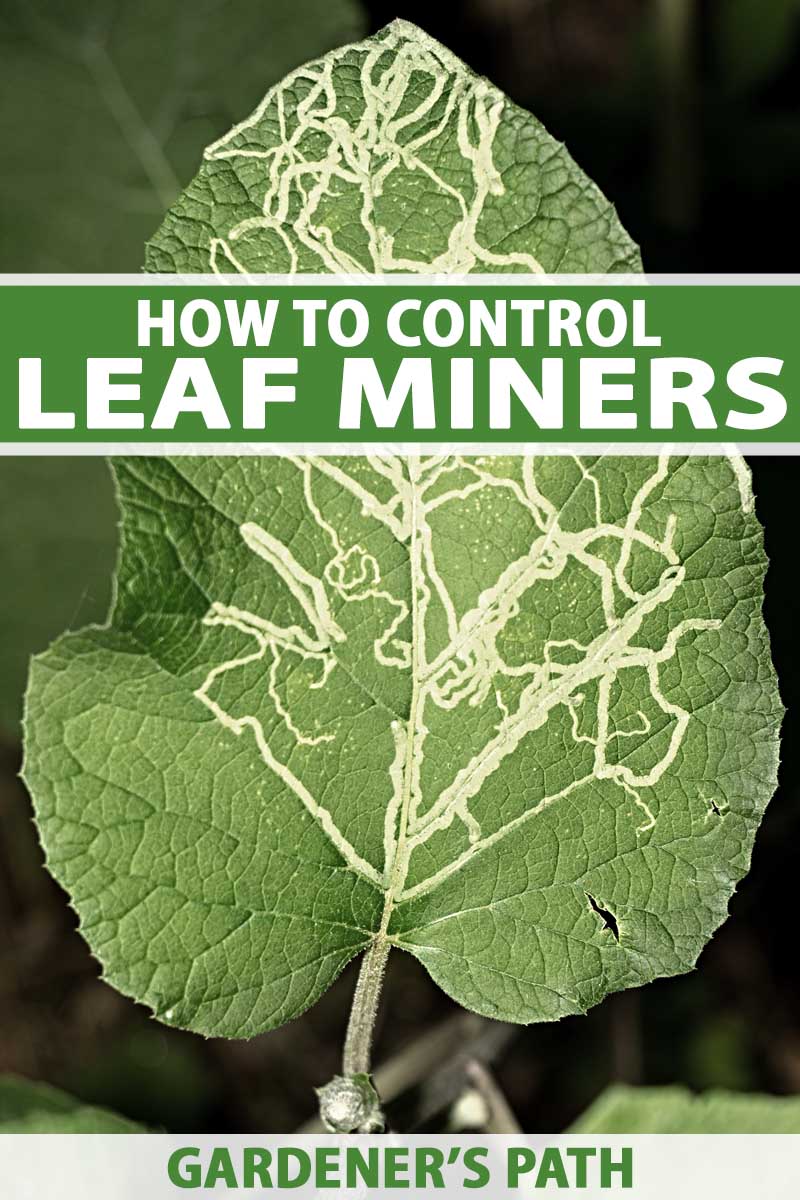

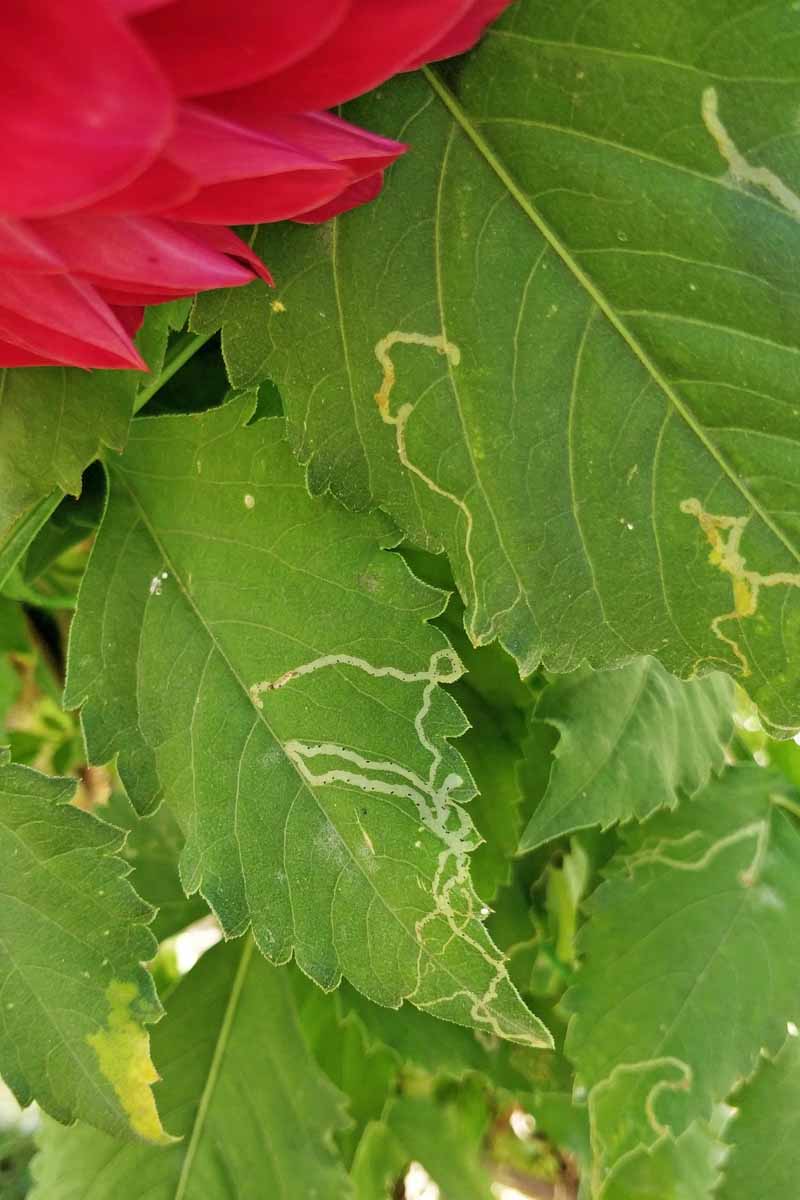

Leaf miners are not just one species of pest. Rather, this common name covers a variety of insect larvae that tunnel inside plant leaves, feasting on the green parts as they go. Sawflies (Hymenoptera), flies (Diptera), beetles (Coleoptera) and even some moths (Lepidoptera) all have leaf mining larval stages. These insects will damage trees, shrubs, herbaceous perennials, and annuals, including vegetables such as beets, spinach, and chard. Feeding dots made by Dipteran adults can closely resemble the unsightly stippling caused by other insects and mites. Along with the larval exit holes, these can become entry points for disease pathogens. The mining damage can be divided into two types: tunnels or blotches. Often, blotches are a result of multiple larvae mining in the same leaf. When dealing with edible greens such as spinach, the thought of eating insect larvae or frass is an unpleasant one. And the damage they cause is not pretty on ornamentals either. But on plants such as tomatoes and belowground crops like onions, the damage is less of a problem since it doesn’t affect the harvestable fruit or roots. Though the damage is unsightly on ornamentals and vegetables, it is usually not lethal, whereas large amounts of damage year after year can weaken trees and shrubs, making them more susceptible to insects and diseases. The tunnels mined by the larvae of any insect order can reduce a plant’s photosynthetic capacity, and in the case of severe infestations, the foliage may wither and eventually drop off.

Identification

Identifying pest species by observing the adults is not easy, since the mature stages of leaf mining larvae often go unnoticed. Unless you observe a mature female laying eggs on your plant and later notice damage, seeing a leaf miner adult flying around your garden doesn’t mean it is the culprit. Though the larvae can be from different insect orders, it can be hard to tell these tiny pests apart as well, as there are few distinguishing features. Since the damage they cause is similar across species, addressing the problem is often more a matter of identifying that you have leaf miners, rather than determining which variety of insect is present. You can try using the host plant’s identity to help you determine which pest may be tunnelling inside, but some insects have broad host ranges. In general, control methods are similar across the board, so figuring out exactly who is doing the chewing is not always necessary. Damage can be misidentified as an abiotic (i.e. not caused by a biological organism) or fungal issue. To double check, pull apart the affected area and look for frass (insect poop) or the larvae themselves. In general, the eggs are tiny, oval, and oviposited either in or near adult feeding sites. Larvae are about two millimeters long, slightly flattened, and transparent or light colored. The pupae can be cream to light brown and are often shiny. The most common garden leaf miners are fly larvae, and these are mainly from the Liriomyza genus. Many of these have wide host ranges. In your garden, you may find mines from the vegetable leaf miner, L. sativae, which primarily affects cucurbits, legumes, and solanaceous plants. Among other crops, the tomato leaf miner, L. bryoniae, likes lettuce, melons, peppers, and chrysanthemums. The American serpentine leaf miner, L. trifolii, likes plants including beans, onions, and celery. And the serpentine leaf miner, L. brassicae, loves brassicas like broccoli and cauliflower. The spinach leaf miner, Pegomya hyoscyami, is also a common fly species in the garden, and as its name suggests, it loves tender leafy spinach greens. The aspen serpentine leaf miner moth, Phyllocnistis populiella, is a familiar sight on all sorts of ornamental trees and shrubs. If you’ve ever wondered why it looks like aspen leaves shimmer with a silver hue in the wind, take a closer look and you’ll probably see winding tunnels filled with lines of frass in the leaves.

Biology and Life Cycle

Depending on the type of insect, eggs are either injected into or laid on the foliage, most often on the underside. As soon as the egg hatches, the larva begins to chew into the leaf, feeding on the layers between the upper and lower cuticle and leaving behind opaque, silvery blotches or tunnels. When ready to pupate, the larva exits the leaf and either pupates on the foliage, or falls to the ground. Dipteran leaf miner eggs, for example, take three to six days to hatch, and larvae are active for one to three weeks and overwinter as pupae. One generation takes about 30 to 40 days to complete, and they can produce three to 10 generations per year, depending on the weather and climate. At 86°F, a life cycle can be completed in two weeks, though it will take seven weeks at 59°F. Lepidopteran leaf miners eggs, such as those of the citrus leaf miner, Phyllocnistis citrella, can take about a week to hatch, and over the next two to three weeks the larvae molt four times. The pupae can take one to three weeks to emerge as adults, and depending on the climate, the entire life cycle can be completed in three to seven weeks. Birch leaf miners, the shared common name for five species from the Hymenoptera order, lay eggs that can take four to 14 days to hatch. The larvae feed for eight to 12 days and, depending on the species, will pupate and emerge as adults in two weeks, or overwinter in the ground and emerge the following season.

Monitoring

Since the adults are often quick-flying flies that are not typically noticed, it is easiest and most effective to monitor for these pests by inspecting the plants themselves for eggs and damage. Flip over the leaves and look for eggs and early mining activity, using a hand lens with 10X magnification to help you see the eggs. In a larger garden, check ten different plants in ten locations. Some growers will set out blue sticky cards, which you can find at Arbico Organics, to trap flying adults and monitor for activity. However, the presence of mature insects does not always necessitate control. Rather, it is a good indication of when to really start looking out for eggs and feeding damage.

Organic Control Methods

Often, leaf miners do not need to be actively controlled by you, thanks to the variety of natural enemies out there preying on them. If control is necessary, try to choose a method or combination of strategies that will not affect natural predator or pollinator populations. The best way to approach any pest issue is with an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy, which combines methods such as prevention, exclusion, and cultural methods for safe, effective control. Learn more about IPM in this guide.

Cultural and Physical Control

While doing monitoring checks, you can either squish the ends of any trails to kill the larvae, or you may remove and destroy leaves with visible eggs or tunnels. Cover susceptible crops with a row cover made from a fine mesh material, such as cheesecloth. This is only useful if the location hasn’t been visited by these pests for at least one year though, since adults can emerge from pupae in the soil and begin laying eggs under the row cover. Take proper care of your plants to keep them vigorous and resilient to damage if these insects do come to visit. Keep your garden clean, removing crop debris and weeds that may be used as alternative food sources – including lamb’s-quarter, pigweed, henbane, and nightshade – during and at the end of the season. Till the garden deeply in early spring and again post-harvest to disrupt any pupae that are hanging out in the soil. You can also use trap crops to monitor for and trap early populations. What plant will work as a trap crop depends on the type of pest, but columbine and radishes will attract some of the common garden types.

Biological Control

Organic Pesticides

Pesticides in general, including organic and non-organic types, are not effective against larvae already snacking inside leaves, and don’t usually provide satisfactory control. Most of the parasitic wasps that attack leaf miners are in the Diglyphus genus, including D. isaea, which is available at Arbico Organics. Diglyphus isaea These tiny, shiny, black opalescent insects prefer warm weather, and can be applied as soon as you see damage. To try and reach populations of pupae in the soil, apply a mix of the beneficial nematodes Steinernema feltiae and S. carpocapsae. NemAttack Beneficial Nematodes NemAttack is a good option that is available at Arbico Organics as well. Learn how to use beneficial nematodes in the garden in our guide.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Like organic pesticides, most chemical pesticides can prevent adults from laying eggs, but have no effect once the larvae are already busy chewing inside the foliage. This way, when they do hatch and chew into the foliage, they’ll encounter some product that will hopefully kill them. Some organic pesticides can provide control, although thorough coverage is required. Bonide Neem Oil Neem oil – such as this product from Bonide that’s available via Arbico Organics – can be useful. Monterey Garden Insect Spray But spinosad products, like Monterey Garden Insect Spray from the Home Depot, are known to be more effective. Once ingested, spinosad immediately halts feeding and will kill the larvae after a couple of days. While it is safe to use with most beneficials, try to apply it later in the day, as it is toxic to bees for a day after application. You can apply it as needed throughout the season. Systemic pesticides, however, can reach those protected inside. Chemicals such as chlorantraniliprole, abamectin, cyromazine, and dinotefuran can be effective. If you decide to use these products on edible plants, check the label for the specific date-to-harvest intervals to ensure you are eating safe products! Many of these chemical options have a negative impact on native beneficial insect populations, and the lack of predators can result in reinfestations. Thus, it is usually best to prevent and control these pests with IPM methods and organic options instead. Though they rarely kill a plant, seeing winding channels filled with frass on your flowers and vegetables is neither aesthetically pleasing nor appetizing. Now you’ve got a variety of methods up your sleeve to prevent and control these little larvae, including working alongside the beneficial predators that nature provides. Have you ever noticed leaf miners at work? Tell us what types of plants they were chewing through in the comments below! And to learn more about about tunneling insect pests, check out these guides next:

How to Identify and Control Allium Leaf MinersIdentifying and Controlling Cabbage Maggots