Not to be confused with the similarly named good guys lacewings, these doily-like insects aren’t a welcome sight, especially on ornamental trees and shrubs. The damage they do to foliage can be confused with that of thrips or spider mites. Luckily, these pets are not nearly as serious or hard to control. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Here’s what we’ll cover:

What Are Lace Bugs?

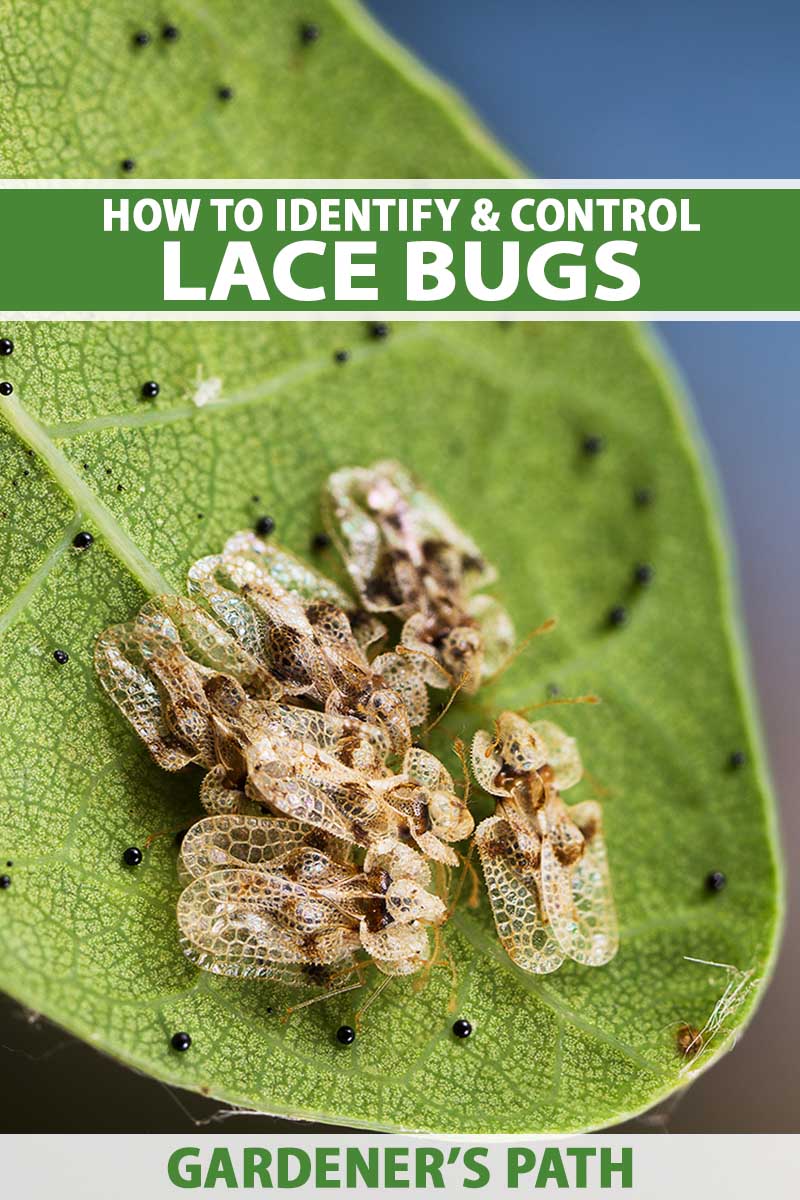

Belonging to the Tingidae family in the Hemiptera – or true bug – order, there are 140 known species of lace bugs in North America. Like all true bugs, the adults and nymphs have needle-like mouthparts which they use to suck sugary plant juices. Lace bugs focus on the underside of deciduous and evergreen tree and shrub leaves, leaving small white or yellow spots on the upper surface. Their hosts include azalea, basswood, elm, hackberry, hawthorn, lantana, oak, pyracantha, rhododendron, and sycamore. The damage becomes most noticeable when populations are large in mid to late summer. If feeding is heavy, leaves may drop prematurely. They also produce small, dark droppings where they feed. These are sometimes called varnish spots. The damage caused by these pests is mainly cosmetic, and usually doesn’t affect the health of the plant, especially when it is a healthy and mature tree or shrub.

Identification

Often, the species you’ll find in your garden are from the genera Stephanitis, including azalea lace bugs (S. pyrioides), Corythucha, which includes hawthorn (C. cydoniae) and hackberry (C. celtidis) lace bugs, or Leptodictya, which includes those that attack ornamental grasses, such as L. plana. There are many other species as well, but these are most common. Though it is not easy to identify these species based on what they look like, these insects make it easy because most are host specific. So, if you notice a suspect lace bug on a garden plant other than your azaleas or the others listed above, it won’t be too hard to find out what type it is. However, because the details of biology, life cycle, and management techniques are the same for all of the pest species, it isn’t critical to find out exactly what type you’re dealing with. In general, the nymphs are dark colored, wingless, and have flat, oval shaped bodies with spines that poke out in all directions. The adults are one-eighth to a third of an inch long, with intricately sculpted, semi-transparent lace-like wings that are held flat and extend beyond their abdomens. Stephanitis and Corythucha adults have flat, rectangular bodies. They are usually transparent to light amber in color. Their eggs are transparent to cream colored, and football shaped. For example, S. pyrioides, the azalea lace bug, is transparent with a dark pattern spanning its wings. C. cydoniae, the hawthorn type, has a dramatic square-edged transparent wings, a thorax cover shaped like elephant ears, and light brown markings. Leptodictya adults are more oblong and elongated than species of the other two genera, and gray-green to light brown in color. They lay deep brown, barrel-shaped eggs. L. plana, for example, are a light green-brown in color, and their wings look like they are made of much finer lace than that of the other two species described above.

Biology and Life Cycle

The life cycle of these insects can take 30 to 40 days to complete, with several generations per year. In the spring, the adults fly to their hosts and begin feeding on the first fresh leaves. They mate and lay small groups of tiny eggs on leaf undersides, near the mid-vein. Some will partially insert each egg into the leaf tissue, and some species seal their eggs in with a brown substance that hardens like a scab over the top. Eggs will hatch into nymphs after about two weeks. The nymphs feed for three to four weeks, and go through five instars as they grow. They leave their molted skins clinging to the foliage. Once matured into winged adults, they mate and lay a second round of eggs, which will hatch, molt, and reach adulthood, and feed until late summer or fall. Stephanitis species overwinter as eggs in cracks in the bark or leaf debris, while Corythucha and Leptodictya species overwinter as adults in host leaf debris. On evergreens, the adults may spend the winter on the surface of the leaves.

Monitoring

To determine when to start management practices, and which control methods to choose, keep a close eye out for these pests before their populations and the damage they cause gets out of control. Damage on the upper side of leaves can look like spider mite feeding damage, but you can easily tell the difference by flipping over the leaf and using a hand lens to find the insects. Plus, lace bugs will leave the undersides looking dirty and stained thanks to the frass varnish spots, shed skins, and egg scabs that they leave behind. And these insects will also bounce in response to being disturbed. Start monitoring for them on susceptible plants in the late spring. Damage is typically noticed later in the season, so waiting for damage is not a reliable preventive method for catching problems in advance.

Organic Control Methods

Overall, these insects can be tolerated on your plants, as they don’t often cause enough damage to justify control. Healthy trees and shrubs will not be significantly affected by lace bug feeding, but their damage will ruin a plant’s aesthetic. In the case of severe damage, control measures may be necessary. While these control methods will not reverse the damage, they will prevent further problems. If so, use an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy to reduce pest numbers by combining a variety of the methods detailed below.

Cultural and Physical Control

Beginning well before pests become an issue, maintaining your plants’ vigor is an essential step, giving your flora a better chance at surviving an insect attack when it happens. When grown in full sun and hot locations, shrubs such as azaleas seem to suffer the most damage from these insects. Grow susceptible plants known to host lace bugs in part shade if possible. The nymphs are wingless, so use a strong jet of water from the hose to dislodge them from the leaf undersides. Keep the soil bare under plants, raking away any leaves or debris to remove overwintering adults or eggs that may be hiding out, or tilling the debris into the soil. Remove any weeds from the garden that may serve as alternate hosts for the bugs. Since each species of this pest has its own specific host, planting a variety of ornamental shrubs rather than a lot of one type will help to reduce spread if an infestation occurs.

Biological Control

Biological control, using the variety of predators nature provides, is a useful long term control method. Natural enemies are highly effective at keeping populations low, and controlling any small outbreaks. Assassin bugs, jumping spiders, pirate bugs, mites, ladybugs, green lacewings, and parasitic wasps such as mymarids will all target lace bugs. Attract and build up a healthy population of these beneficial insects by planting an array of flowering plant species in your garden.

Organic Pesticides

Chemical Pesticides

Systemics such as imidacloprid and dinotefuran are also useful. These are chemicals that are absorbed and transported around the plant. But avoid applying them during the day or to flowering plants because these are toxic to pollinators. Since these insects hide on leaf undersides, good coverage of these areas is necessary. Pyrethrin, available at Arbico Organics under the name PyGanic, controls a wide variety of pests including lace bugs. PyGanic Insecticide Horticultural oils can be effective as well, and Monterey Horticultural Oil is available from Arbico Organics. Monterey Horticultural Oil Or try an insecticidal soap, such as this one from Bonide, which is also available at Arbico Organics. Bonide Insecticidal Soap Apply these products when nymphs are abundant. Often, these products will need to be reapplied every two weeks or so to achieve and maintain control. Bifenthrin, cyfluthrin, permethrin, and other pyrethroids are useful. Carbaryl products such as Sevin, which is available at Home Depot, are another effective option. Sevin Insecticide As with organic contact products, chemical contact pesticides must be applied properly to fully cover the undersides of the leaves. Keep in mind that chemicals are generally toxic to beneficial insects. Since many of the recommended lace bug control methods are biological, using them can undo all of your hard work, reducing or wiping out predator populations. This will give the pests a chance to recover and keep feeding on your plants. Their damage can be ugly, but luckily you now know how to deal with these bugs, whether it be culturally, by relying on beneficial insects already present in your garden, or applying a pesticide. Have you ever seen one of these bizarre looking insects? Let us know down in the comments what species you think you spotted, and how you dealt with them if you had to break out the controls. Next up, read more about other sap-sucking pests that may infest garden plants here:

How to Control Aphids on RosesHow to Identify and Control ThripsHow to Detect and Control Spider Mite Infestations