Those sweet, crisp roots were supposed to feed you and your family, not some small, hungry weevils! What can you do? We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Everything you need to know about these weevils and how to do just that is laid out for you below! Here’s what we’ll cover:

What Are Carrot Weevils?

These weevils are native to North America and though they can be pests nearly everywhere on the continent, they are a particular problem in the eastern United States and around the Great Lakes in both the US and Canada. As their name suggests, they love carrots, but will also attack other members of the Apiaceae family, including celery, parsley, and parsnips. The snout-nosed adults do nibble on the foliage, but their larvae are the real problem, attacking the roots with gusto. The feeding tunnels they create are great entry points for pathogens. But carrot rust flies also attack the orange roots, so how can you tell which pest you’re dealing with? Take a closer look at the tunnels. Carrot rust fly damage is mainly focused on the bottom two-thirds of the root and the feeding tunnels will be rust colored. Carrot weevils leave dark tunnels, often gaping open, and their damage is often concentrated in the upper third of the root. Of course, if you see the larvae of either type inside, you can get out your hand lens and try to identify which pest is the problem. We’ll talk about that in the next section.

Identification

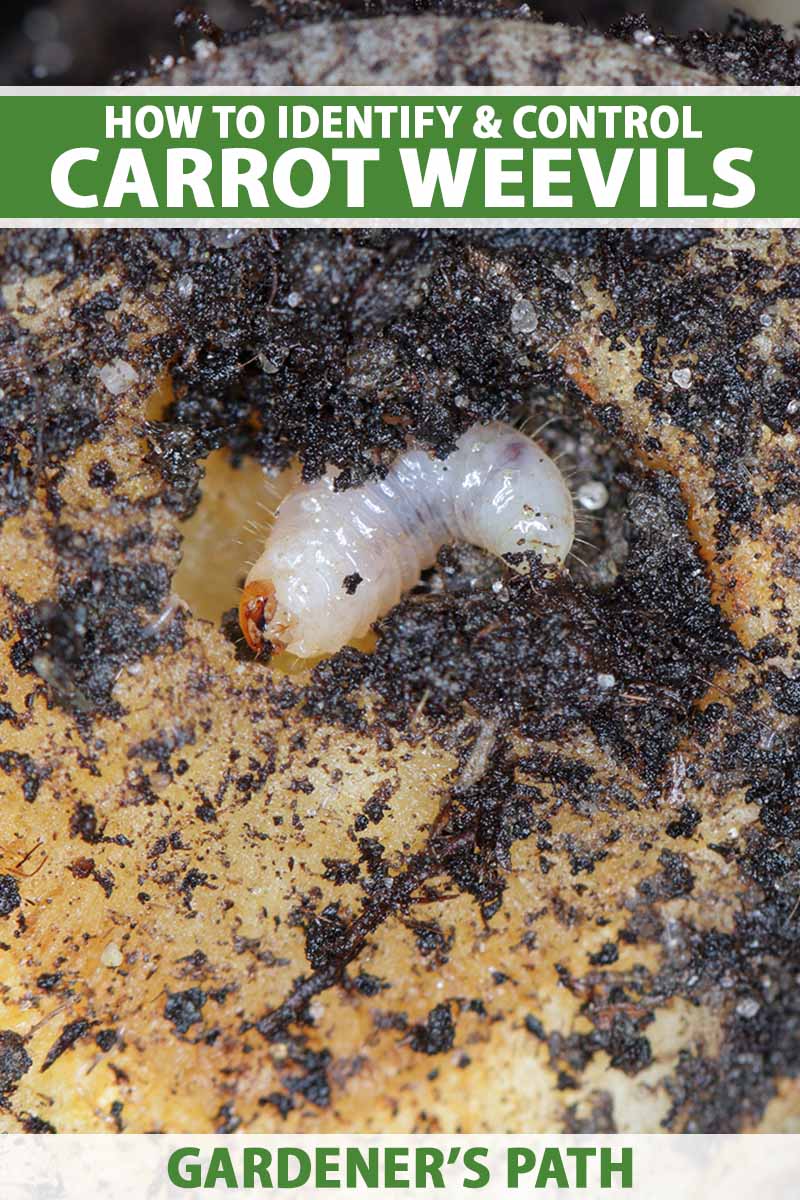

The eggs this pest lays are white, slowly darkening as they mature and turning black just before they hatch. The larvae are cream-colored grubs with no legs and a light brown head capsule. If you see larvae and wish to identify whether you have a Psila rosae problem or a L. oregonensis problem, carrot rust fly larvae are stiff, white to yellow-brown colored maggots. The pupae, like the larvae, are also cream colored. The adults are six millimeters long, dark brown-gray snout-nosed beetles.

Biology and Life Cycle

These pests disperse by walking, not flying. (This is an important fact for later). Females chew a hole in the petiole or crown of the young plant and lay two to four eggs inside, covering them with a dark, sticky secretion. This mark is known as the oviposition scar. In one to two weeks, the larvae hatch and chew tunnels down into the root. Young plants may wilt and die as a result. After going through four instars, they pupate, and then emerge as adults. These pests can complete one to two generations per year.

Monitoring

Egg laying begins mid-May to early June, when the plants are past the four-leaf stage. Degree day models have been developed for this pest. When we talk about degree days, we mean an accumulation of days above a certain temperature, in this case 45°F or 7°C. Egg laying starts at 147 degree days, and a total of 630 are needed to complete one generation. This is helpful to know as it allows farmers to predict when oviposition, for example, is likely to be happening. You can watch for oviposition scars on the foliage and crown of the plant, but at that point the damage has already been done, and they are tiny and very hard to find. Traps are a more popular and straightforward option to see if you have a weevil problem. A specific type called Boivin traps are made by strapping together two foot-long pieces of wood with grooved “teeth” on the edges for the weevils to hide in as they feed on the carrot bait in the hollowed out center. Check the trap every three to four days and replace the carrot before it starts rotting. On commercial farms, an average of one and a half weevils per trap warrants intervention.

Organic Control Methods

In this section you’ll find a variety of control methods you can employ as part of a complete integrated pest management (IPM) strategy to attempt to control these unwelcome insects.

Cultural and Physical Control

Physical control could mean hand-picking the offending insects off the plant, or in this case, excluding them from the crop by covering the plants as soon as they emerge – or earlier – with floating row covers. Cultural methods often allude to adjusting planting and growing conditions and parameters to evade the pest and give the crop the upper hand. Often, these methods take advantage of the pest’s biology and lifecycle. For example, since overwintering is accomplished near the host plants and the adults are weak fliers, you can use crop rotation strategies to avoid planting in the same spot as you did the previous season. This should help you to avoid the majority of the first hatch. Control alternate host weeds, such as hemlocks, wild carrots, and other Umbelliferae family members surrounding the garden to reduce overwintering sites and remove additional food and oviposition sites. Rather than harvesting a carrot here and there, harvest entire blocks or rows at a time. Clear out any crop residue at the end of the season as well. If possible, delay planting until after when most of the first-generation adults will have died, which could be in mid-June.

Biological Control

Organic Pesticides

Unfortunately, there are no organic pesticides proven to be effective against these pests. Though they have limited effectiveness in large scale commercial monoculture, in your smaller and more diverse garden, they could do some damage to the carrot weevil population. Limit foliar insecticide use and grow plants that provide nectar and other food sources to attract and feed the adults. Some types of beneficial nematodes will attack these pests, specifically Steinernema carpocapsae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, which are available at Arbico Organics in a combo pack. Beneficial Nematodes Apply these nematodes mixed in water at or just after planting to allow them to establish and work preventatively. Beauveria bassiana products may affect a larva here and there, but trials show that applying these types of fungi-based products has no effect on damage and outcomes overall. If you wish to apply a product to control these pests, chemical pesticides are your best bet.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Because the larvae are safely hidden in the roots and the adults have limited susceptibility to chemicals, chemical pesticide choices are limited. Some insecticides used by commercial farmers are malathion, diazinon, methomyl, and certain pyrethroids, but as stated above, using chemicals is not the silver bullet. In your home garden, chemical pesticides are also not the answer to every insect problem, often killing more of the good insects than the bad, leading to a boom in the bad insect populations that’s unchecked by predators. Plus, creating a good environment for their predators and parasites by growing a diverse garden – and one that’s chemical-free, if possible – is imperative. That is, if you want less damage and more of a harvest that looks like this: Have you ever had issues with these pesky weevils in your garden? Let us know in the comments below how you noticed and how you dealt with them! While you’re at it, read about other carrot pests and more on how to grow these delicious crunchy root vegetables here:

How to Grow Carrots in the GardenHow to Identify and Control Carrot PestsHarvest Time: How and When to Pick Carrots