Heck, I even tried growing the next-to-impossible-to-cultivate wasabi last year because I love fresh wasabi so darn much (let’s just say I have some work to do figuring that one out). But there’s a special place in my heart for a plant that you can plop in the ground and essentially forget for a few months. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. That’s one of the (many) reasons why there will always be a place in my garden for mitsuba. Shade, sun, clay, sand… mitsuba can handle it all. It’s also particularly untroubled by pests and diseases. Mitsuba’s easy care isn’t the only reason I love this veg, though. Mitsuba is a two-for-one wonder in that not only does it serve as a flavorful herb, but it can also be grown as a vegetable. Sort of like using the fennel bulb to make a salad and seasoning your soup with the chopped leaves of the fennel tops. You can also eat the root, flowers, and seeds – make that a five-for-one wonder! Oh yeah, I almost forgot to mention that you can also grow it as an ornamental. Seriously, why isn’t mitsuba featured in every garden? Unfussy, pretty, and delicious? Be still my heart! Up ahead, we’ll talk about all the work you don’t have to do to make mitsuba happy, along with some recipes and ways to use this versatile veggie. Here’s what you’re in for: I realize that some people aren’t super familiar with mitsuba, though it features heavily in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean cuisine. So before we get started, how about a quick introduction to your new best friend?

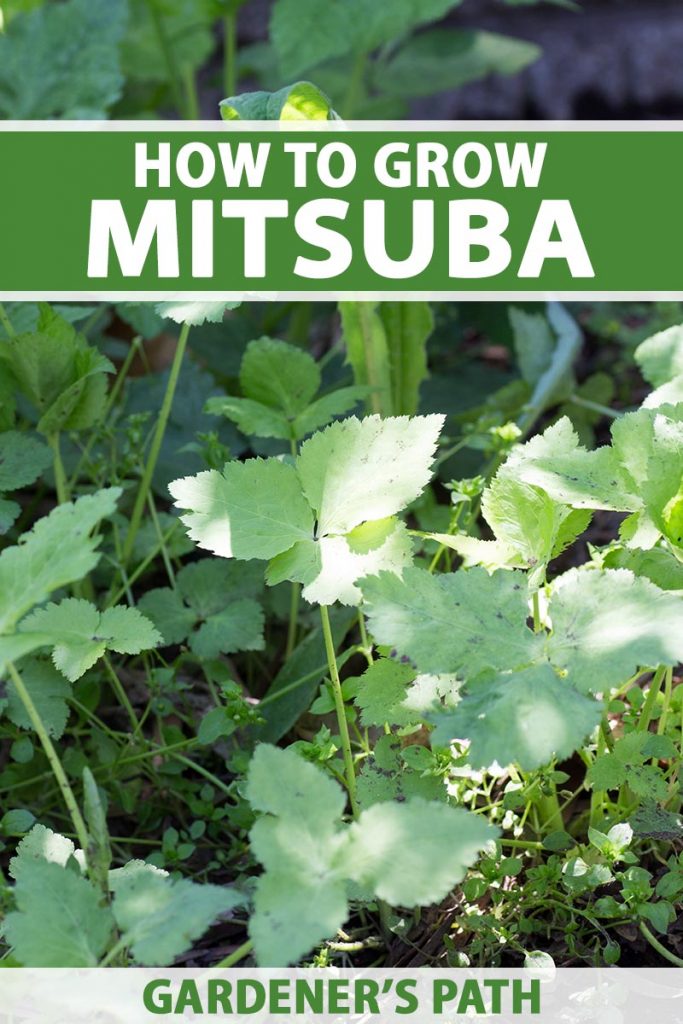

What Is Mitsuba?

Mitsuba is part of the Umbelliferae (Apiaceae) family, which includes carrots, dill, parsley, lovage, and fennel. Not as widely known in most parts of the United States and Canada as some other herbs, it’s a common and well-appreciated plant in East Asia, where it grows wild.

While the species name “japonica” indicates Japanese origins, “cryptotaenia” is another word for the honewort genus. The name mitsuba is Japanese for trefoil, or three-leaf. No doubt the plant was named thusly because of its three ruffled leaves per stem, which makes it somewhat resemble Italian flat leaf parsley and cilantro. You may also see the common names Japanese parsley or chervil. It grows up to three feet tall and two feet wide in its native habitat, but in your garden, the plant will probably top out at about two feet tall and a foot wide since it won’t have the exact woodland conditions it prefers in the wild. In the late spring to early summer, it produces umbels of small white, lavender, or light pink star-shaped flowers followed by seeds that ripen in the late summer. The taproot is long and deep, similar to a carrot. It tastes something like a mix of chervil, coriander, and lovage or celery leaf, with a touch of bitterness depending on how much light it is grown in. Don’t confuse mitsuba with its close relative, Canadian honewort (C. canadensis). Sometimes called wild chervil, this plant is native to to the eastern half of North America, growing from New Brunswick to Florida. While mitsuba doesn’t do well once temperatures rise above 90°F, it can survive down to about 14°F. It will die back in the winter and reemerge in the spring. It also self-seeds freely, so if you let it go to seed, you’ll have new seedlings popping up as the weather warms.

Cultivation and History

Mitsuba grows well in USDA Hardiness Zones 4a-9a. In the wild throughout China, Japan, Thailand, and Korea, mitsuba thrives in woodland and mountainous areas.

You’ll usually find it in the forest understory, growing in dappled shade in loamy, moist soil or in disturbed areas like roadsides and ditches. In Japan and Japanese communities outside of the country, the plant is commonly cultivated as a vegetable and is considered one of the dento-yasai, or traditional vegetables in the country. In other parts of Asia and in North America, it’s used primarily as an herb.

It’s a self-sowing perennial, though many grow it as an annual, harvesting the whole plant once it’s ready to eat.

Propagation

Mitsuba is often easier to find in seed form rather than plugs or seedlings in many areas. Fortunately for those who don’t have access to live plants, it grows readily from seed. Particularly if you have clay or sandy soil, work in some well-rotted compost to amend it before planting.

From Seed

Sow seeds directly outdoors after the danger of frost has passed in the spring. You can also plant in the fall if you live in Zone 9a. Insert seeds a quarter of an inch deep in prepared soil. Keep the seeds evenly moist. If you’re having a dry spring, a plastic or glass cloche can work wonders to help keep the moisture in while the seeds and seedlings are maturing. The seeds should germinate in about a week or two. Thin them to about six to nine inches apart once they’ve grown about three inches tall, and feel free to eat the little sprouts that you pull – they’re delicious. 13-Inch Plastic Plant Cloche Plant every six weeks for a continuous supply.

From Transplants

It’s not too common to find a transplant at the nursery in the US, though you might. You can also frequently find live mitsuba with roots intact at any grocery store that specializes in Japanese or Chinese ingredients. You can plant these just as you would a transplant from the nursery. Gently loosen the roots and set the transplant in a hole about the same width and depth as the root ball. Pack soil around the roots and water well to help the roots settle.

From Divisions

In the autumn, if you aren’t harvesting the entire plant, you can feel free to divide your remaining plants and share some with neighbors or expand your mitsuba patch more rapidly. To divide, dig up the plant, and roots and all. Gently knock away any loose soil. Trim the plant in half using a pair of clippers or heavy-duty scissors to cut through the roots and up through the crown. Put one half back in the ground and fill in around the plant with soil. Plant or use (or give away) the other section as you would a transplant.

How to Grow

This plant can grow in anything from full sun to full shade, but it tastes more bitter and the leaves may turn yellow when growing in full sun. It’s tolerant of most soils, from clay to sandy types, but it prefers moist, well-draining soil. If you stick a finger down an inch below the surface and it feels dry, it’s time to add water.

In heavy clay soil that doesn’t drain well, plants might not grow as large, and it might be difficult to keep porous sand moist. This where working compost into your soil makes all the difference!. Don’t freak out if your soil gets a bit dry and your plant looks limp. Just add some water and it will bounce back. Mitsuba can tolerate periods of dryness, but you’ll have a bigger harvest if you keep your crop moist. Heap an inch of compost, or a mulch such as straw or dried grass clippings, around the base of the plant to help retain water. There’s no maintenance like fertilizing required so long as you worked some compost into the earth when you planted. No pruning is necessary, but you might want to pinch the flowers out to prevent self-seeding. Mitsuba can spread if left to its own devices.

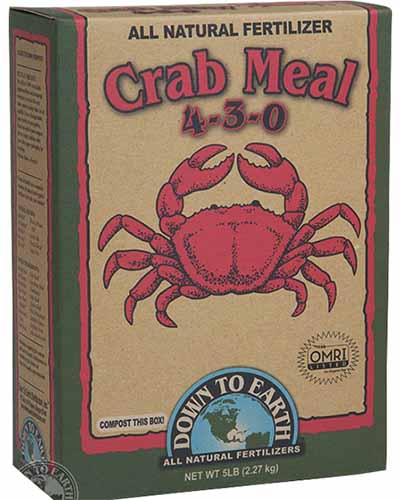

Down To Earth Crab Meal I prefer to side dress each plant with two ounces of a fish-based meal like Down To Earth’s Crab Meal, which has an NPK ratio of 4-3-0 – just right for growing leafy vegetables/herbs. If you don’t have fish meal handy, you can purchase crab meal at Arbico Organics in a five-pound box. If you grow your mitsuba as a perennial, give it a feeding once in the early summer and again in the early fall.

If the plant begins to spread too much for your garden space, divide it as described above. If you’re growing the Kanto variety (more on that in a bit), wait about 60 days or until the stalks are about eight inches long. Then, heap straw or soil around the stems and leave it in place for two weeks to block sunlight, promoting the best flavor in your crop. At that point, harvest the blanched stems.

Growing Tips

Work compost into the soil when planting to improve drainage and, water retention, and provide nutrients. Keep the soil constantly moist. Don’t let it dry out. Pinch the flowers to prevent self-seeding.

Varieties to Select

In Japan, there are two main varieties: Kanto and Kansai. There’s also a form sometimes called purple or purple-leaved.

Kanto

The shiro-mitsuba variety (or white honewort in English) has large, pale stalks that lend themselves perfectly to blanching, which is how they are handled in Japan. Growers mound soil or straw around the stalks for a few weeks before harvesting to turn them pale and creamy white. This type grows about two feet tall and a foot wide when mature, and it has white flowers. Kanto is a region in central Japan where the veggie is particularly popular. The seeds and live plants are hard to find outside of the country, so if you see any, nab them!

Kansai

Named after a region in the southern part of Japan, the Kansai type has deep green leaves and stems. This veggie is typically grown for its leaves and is used as an herb to flavor dishes rather than for its stalks. It grows to be about two feet tall and a foot wide with small white flowers when it blossoms.

Purple Leaf

C. japonica f. Atropurpea has bronze-purple leaves and stems, and pink or lavender flowers. It does best in Zones 4-7 and is a bit more compact than the other varieties. It grows to about 18 inches tall and a foot wide. This form is particularly lovely as an ornamental option thanks to its large, colorful leaves.

Managing Pests and Disease

Mitsuba is one of those plants that just doesn’t seem to have many common pests or diseases that you’ll be forced to face. In fact, there’s really just two things that may cause you trouble: slugs and snails, and downy mildew.

Insects

Mitsuba is wonderfully untroubled by most pests out there. It’s one of the few plants with which I’ve never had to deal with an aphid infestation. There is one thing that might trouble you, however (cue the scary music): Gastropods are the one type of pest you really have to watch out for. Those little slimers just can’t resist Japanese honewort. You may see slimy trails around your garden or leaves that appear to be nibbled on.

Or, if you’re like me and have a lot of slugs oozing their way around your garden beds, you might come outside in the morning and discover your seedlings or entire stems have gone missing. Thank heaven slugs and snails are fairly easy to control in the garden, whether that means putting out pellets or drowning them in beer. Our guide to protecting your garden from this common foe will help you win the war.

Diseases

Disease isn’t common with mitsuba, but if you do come across it, it will likely be in the form of downy mildew.

Downy Mildew

Downy mildew is a common disease of many plants that like cooler temperatures between 50 and 70°F and that grow in moist conditions – just what mitsuba prefers. Downy mildew is a water mold (oomycete) from the Pseudoperonospora genus. It looks like a fungus, but it’s more closely related to algae than a true fungus. On mitsuba, it causes a gray growth on the undersides of leaves, and the tops of leaves may form yellowish spots. To help prevent it, keep plants well-spaced and water at the soil level rather than on the foliage.

Harvesting

You can eat this plant at any point, but it takes about 50 days to reach maturity as an herb. If you’re harvesting the plant for the stalks, it takes a bit longer, closer to 80 days.

BioSafe Disease Control RTS You can purchase a 32-ounce container of this product to attach to your garden hose at Arbico Organics. Harvest the plant as an herb when it’s between five to seven inches tall, and as a veggie when the stalks are between eight to 10 inches tall. The larger the leaves get, the more bitter they become, so don’t wait too long to harvest.

Dig up the entire plant and wash the root thoroughly, or slice off the leaves at the root level. Store in the refrigerator wrapped in a light cloth or paper towel inside a plastic bag for up to a week. The leaves last longer when attached to the stem. Don’t wash the leaves until you’re ready to use them. If you sprinkled more seeds than you needed at planting time and then thinned them out, use the sprouts on sandwiches, as a soup topper, or in salads. You can also plant mitsuba as a microgreen. The sprouts should be ready to use in about three to four weeks. If you want to harvest the seeds, clip the seed heads once they start to turn dry and hang them upside down in a cool spot with good air circulation. Once they have dried completely, rub them between your hands and gently blow to separate the seeds from the chaff. Intend to eat the root? Harvest before the plant goes to seed by gently digging up the entire plant with a garden fork. While the roots are edible after the plant goes to seed, they turn tough and bitter as they age.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

There are endless ways to use this tasty plant in your cooking. Fresh, use mitsuba as a salad green, a garnish, or chop it up and use it anywhere you’d use fresh herbs like cilantro or parsley.

Parboil the entire stalk with the leaves attached and serve it as a vegetable side dish. Add it toward the end of cooking soup, but don’t cook it for too long. Just a minute or two will do it, otherwise the plant turns bitter. Or you can toss it into the cooked soup just before you serve it. In traditional Japanese cuisine, the stalks and leaves are steamed briefly and then blanched or dipped in an ice bath to stop the cooking process. The veggies are then served cold and drizzled in soy sauce or dashi (this technique and the resulting dish are both known as ohitashi).

Chefs may also rub the stalks between their fingers to soften the stem before tying it a knot and using it as a soup garnish. The knot is an important symbol in Japanese culture. One of my favorite recipes is to make a hot pot soup in a donabe (you can also use a Dutch oven). In four cups of boiling dashi or miso broth, add a cup of diced tofu and a cup of veggies (chopped carrots, potatoes, parsnips, broccoli, and so on) and simmer for 15 minutes.

Add a dash of sesame oil and a dash of rice vinegar to taste. Add a handful of chopped mizuna and a handful of mitsuba stalks with the leaves attached and remove from heat. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Mitsuba is also delicious in sukiyaki, a Japanese dish made with beef and vegetables in a single pot. Chop up and cook the root or eat it sliced raw. It’s delicious shredded and used in salads or as a sandwich topping. The seeds taste fantastic ground up and used as a spice. They taste similar to the leaves, but a touch stronger. If you pinch the flowers to prevent them from going to seed, toss them on top of your salad or just pop them in your mouth. They, too, taste like the leaves and stalks. Given its credentials, I think it’s only a matter of time until it becomes as common as parsley and cilantro in home gardens throughout the US.

Once you’ve plucked your first batch of Japanese honewort, please come back here and tell us about your experience. Did you run into any problems? Any tips for using up what I’m sure will be a robust harvest? Did this guide leave you feeling ready to tackle the world of mitsuba? If so, you may want to check out some of our other guides on growing Umbellifers next:

How to Plant and Grow Dill How to Grow and Care for Angelica Growing Lovage: An Uncommon Herb with Many Uses

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product Photos via Arbico Organics, Kitazawa Seed Company, and SYITCUN Store. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.