There is another type of hibiscus that has been slowly gaining in popularity in more northern climates for over 100 years now, and breeders have been expanding selections continuously through that time. The term “hardy hibiscus” generally refers to a few different species and their hybrids, in the rose mallow group within the Malvaceae family, that are closely related – to the extent that they can crossbreed.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. In this article, we’ll delve into the details of how to grow these magnificent plants, with the power to add a touch of tropical sophistication to your garden.

I’ll include some of the best cultivars to look out for, and some tricks to ramp up and prolong blooming as well.

What Is Hardy Hibiscus?

When I first discovered hardy hibiscus many years ago in a municipal park, I was amazed that such a glorious plant could grow in southern Ontario, Canada where I live.

I’d seen hibiscuses in the tropics, but the flowers on hardy hibiscus rivaled even their size and brilliance! The famed tropical cultivars mostly come from H. rosa-sinensis, incidentally, with other species, mostly from Asia and Africa, hybridized into the mix. For the purposes of this article, we’ll be focusing on the North American species of Hibiscus that I fell in love with and have been growing for several years now. These are part of the Muenchhusia section of the genus, also known as rose mallows. The hardy hibiscus label is also sometimes bestowed upon another hardy species in the genus (and another one of my personal favorites), H. syriacus – commonly known as rose of Sharon. The rose mallows are herbaceous perennial plants that completely die back to the ground each winter, while rose of Sharon is a small deciduous shrub.

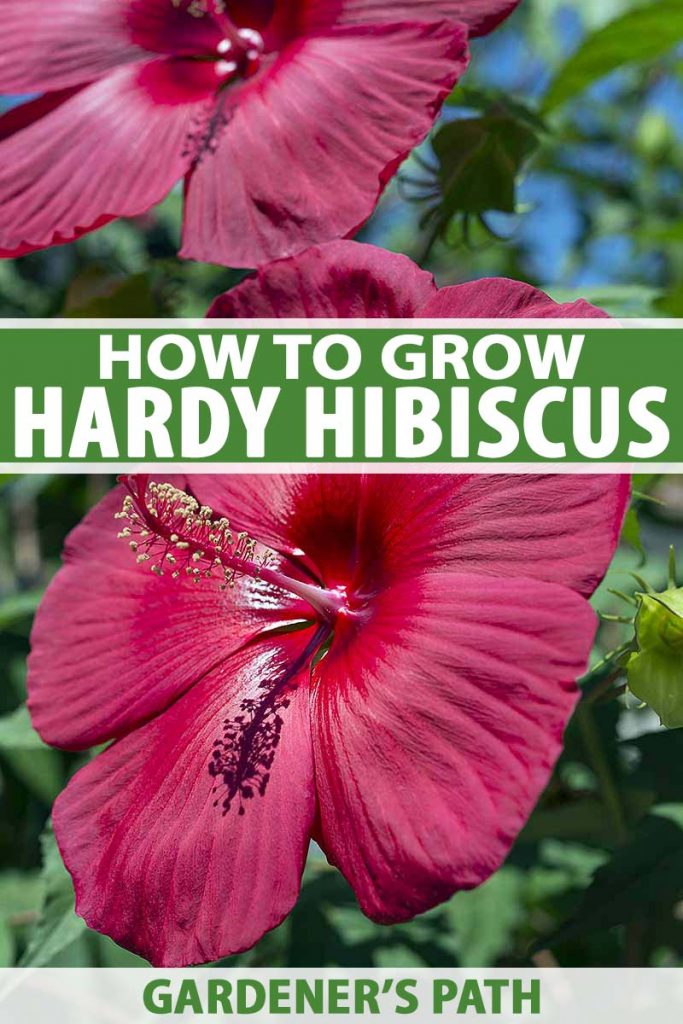

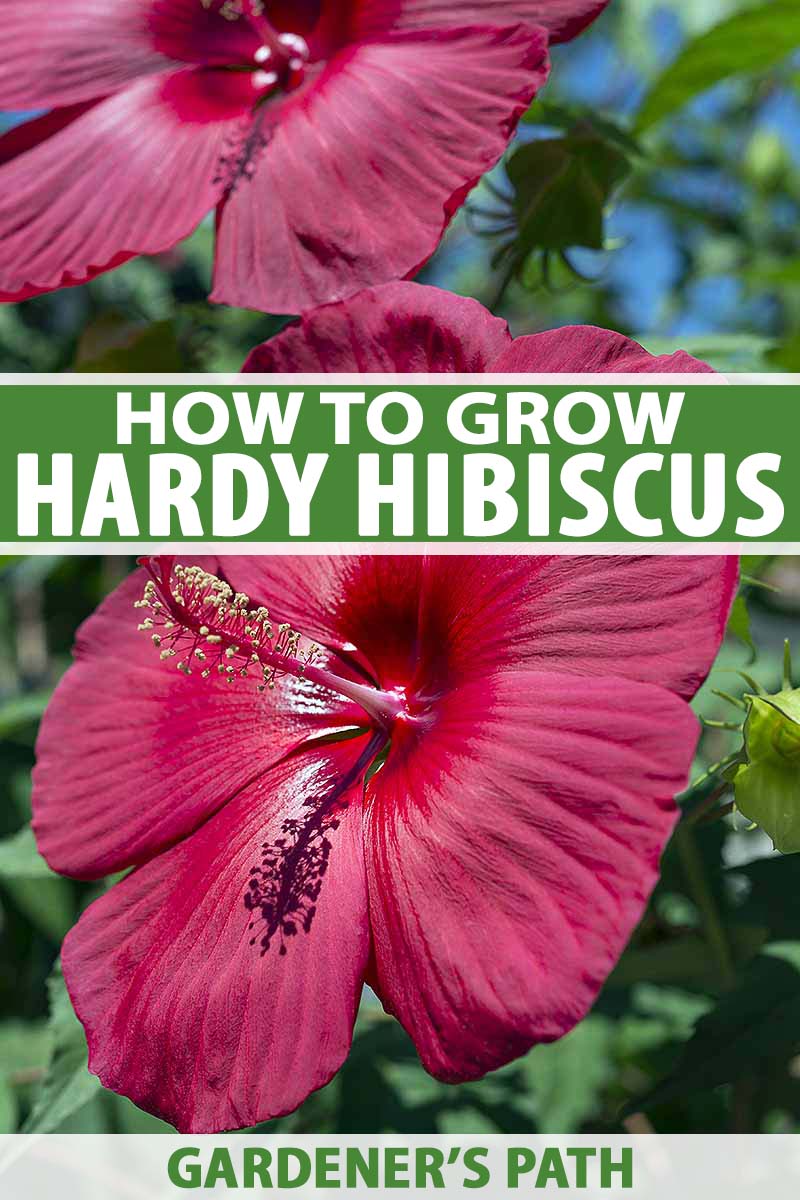

Hardy hibiscus species include H. moscheutos (rose mallow), H. coccineus (scarlet rose mallow), H. dasycalyx (Neches River rose mallow), H. grandiflorus (swamp rose mallow), H. lasiocarpos (hairy or wooly rose mallow), and H. laevis (halberd-leaf rose mallow). Many cultivars of hardy hibiscus sold at garden centers are labeled simply as “Hibiscus x” or perhaps Hibiscus x moscheutos, for example, with the true and complete genetic origins obscured. One thing all varieties have in common, though, is their large, eye-popping flowers that can be up to 12 inches across (though usually they max out at 10 inches). These aren’t just the largest perennial flowers in North America, they’re one of the largest flowers in any garden, anywhere!

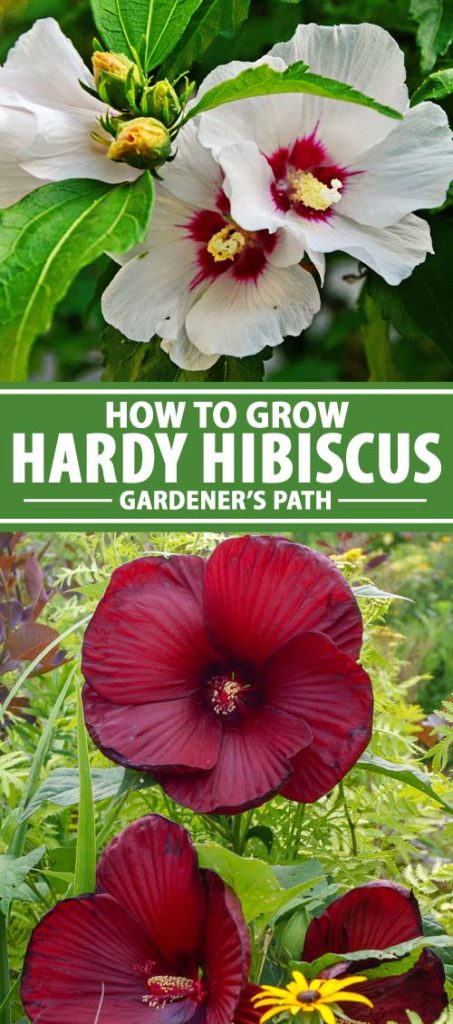

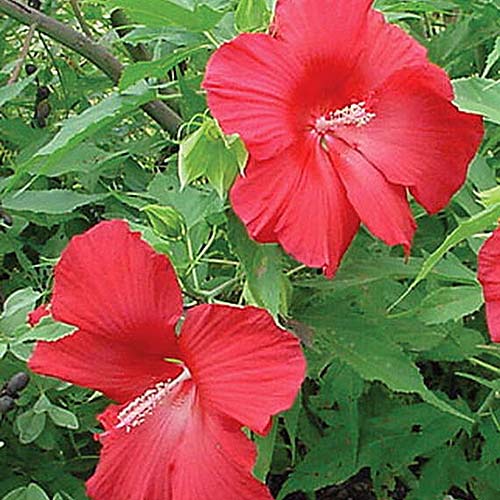

Depending on the genetic background of a given species, hybrid, or cultivar, flowers can be much smaller, however, and can range in color from bright red to pink-blushed white, blue, or purple, often with red or burgundy throats, and various colors of streaks to the flower edges. Like all hibiscuses, hardy hibiscus flowers also have that prominent pollen-coated staminal column, giving them an extra dimension of interest. Different varieties can grow anywhere from two to 10 feet tall and all share common growing requirements – I’ll go into more detail on this below, so keep reading! They commonly begin flowering as early as June in warmer areas, while in cooler areas they may not begin blooming until August, and continue their display until first frost.

Cultivation and History

Hardy hibiscus flowers are hard not to notice in a garden, and they are especially impressive when grouped together in progressive patterns of complementary colors – white flowing into light purple, flowing into darker purple and shades of red, for example.

The plants typically grow in USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 5 to 9, though some species and varieties may be hardy down to Zone 4, or thrive in warmer temperatures up through Zone 11. Many pollinators adore hardy hibiscus – I’ve seen more than one bumblebee within the flowers, cuddling up to the staminal column as if they were exuberantly and intimately greeting a long-lost lover.

And if you like hummingbirds, hardy hibiscus also attracts these dashing little creatures to the garden. The history of hardy hibiscus is a long and interesting one, as plant breeders have been working away on hybrids for over 100 years. However, Gretchen Zwetzig, owner of one of the oldest breeding companies, Fleming Flower Fields, has written that breeding efforts really only began to take off in the 1950s.

While early efforts were focused mostly on H. moscheutos and H. coccineus lineages, the ‘60s brought increased interbreeding with other species, according to Zwetzig. The 1970s brought further innovation, when, for example, Robert Darby introduced varieties that are still popular to this day, including ‘Lord Baltimore’ and ‘Lady Baltimore.’ Since then, breeders have continued to release interesting cultivars, some of which we’ll go over below.

Propagation

Hardy hibiscus is best propagated by seed, stem cuttings, or crown division.

From Seed

Growing from seed is an excellent way to grow a lot of plants at low cost. Just remember, if the seeds are from hybrid plants, it’s impossible to know what you’ll get. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, if you’re looking for variety. Seeds should be started indoors three months before the last frost in Zone 6, or in colder areas. In Zone 7 or warmer, you can start them 1-2 months before the last frost, or sow them directly in a prepared bed after the last frost date. Whatever your circumstance, soak seeds overnight and plant 1/2 inch deep. For planting in flats, keep them at around 50-60 percent humidity if possible, in full sun. As you approach last frost, begin hardening them off by gradually exposing them to outdoor sun and wind when the weather is favorable, starting with 30 minutes the first day, and increasing an hour each day for 5 more days before transplanting. If you want to take a shot at breeding your own crosses, take a look at this paper on hybridization, published in the Japanese Society of Breeding’s “Breeding Science” journal in 2016, to get some ideas on how to do it.

From Cuttings

The best time to take cuttings is in the spring or early summer, ideally before flowering.

Here’s how:

- Prepare a pot of moistened medium consisting of 50 percent soilless potting mix and 50 percent perlite.

- Cut a piece of new growth (softwood) four to six inches in length.

- Remove buds from the lower half of the cutting, moisten the cut end, and dip it in softwood rooting hormone powder. To avoid getting the powder wet, pour out what you need before dipping.

- Poke a hole deep into the growing medium, about half the length of the cutting and wide enough to avoid rubbing the rooting powder off. Carefully insert the lower half of the cutting and tamp the planting medium around it.

- Place the in a warm area with consistent temperatures of at least 60°F, in a greenhouse with 50-60 percent humidity, or in a sunny window covered with a humidity cover or bag.

- Keep the cutting moist. Watering with 1-3 percent hydrogen peroxide every 2-3 waterings will reduce the chance of rotting. If successful, leaves will start to develop in about two months. Once you see roots beginning to creep out the bottom of the pot and the cutting is well-rooted, repot in a 10 or 12-inch container, and place it out in a greenhouse or sunny window for a season before transplanting outside.

From Crown Divisions

Crown divisions are done with mature, fully grown plants that have many stems and a healthy root system. The best time for making divisions is in the spring or early fall, when soil is moist.

Unlike some perennials, hardy hibiscus planted from seed should be divided carefully without digging up the entire root system, since their taproots will be forever impaired if you do this. Plants grown from cuttings tend to develop shallower taproots, in my experience, but avoiding root disturbance is always a good idea with these plants nonetheless. To carry out divisions:

- First, push any mulch away from the area you’re working in so you can reuse it.

- Start 12 inches back from the plant and dig about 2 feet under the root system, or as deep as you can get on one side of the plant to lift up a small section with a few stems.

- Try not to break the larger primary roots as you tease the roots away from the plant.

- Use a clean, sharp knife to cut a piece of the root mass away that is attached to the targeted stems, being careful not to disrupt the connection between root and stem.

- Trim any diseased or dead root mass away, and replant or pot and fertilize with transplant fertilizer. If replanting in a bed, prepare the site as described below. If using a pot, select one that’s a couple of inches larger than the root mass. Repot in a bigger container or trim roots back whenever plants become root-bound. You can learn more about dividing perennials in our guide.

How to Grow

Now that you know how to propagate hardy hibiscuses, let’s go over how to keep them healthy and blooming brilliantly.

Site Selection and Preparation

Hardy hibiscus species are usually found in the wild near wetlands or rivers, which explains their love of moist, relatively rich soil.

Luckily, because of extensive breeding, most hybrids aren’t quite as water-dependent as wild plants. In general, they prefer medium to wet, well-drained soil and do best in soils that aren’t overly heavy, while performing poorly in sandy, dry soils. Sandy or poor soil should be amended with a couple of inches of compost worked in 8 inches deep before planting. This isn’t the sort of plant you can just pop into the middle of your lawn and call it a day, in other words.

If you’re in a cooler climate in Zones 4 to 6, you’ll see the best results if you choose a planting site near a south-facing wall or a slope that is protected from the prevailing winds. Plant them in full sun to encourage maximum bloom – though in hot, sunny climates you should consider arranging them so they get a bit of shade, with a maximum of 6 hours of sun per day.

If they get too much shade, however, they tend to develop long, leggy stems and may not flower well or at all. Although these plants tolerate heat and humidity, the soil must be kept moist, and they prefer their roots to be protected with a good layer of mulch.

Plant Nutrition

Hardy hibiscus plants require nutrient-rich soil to produce their luscious blooms.

I usually use a balanced slow-release organic fertilizer on my entire garden – 4-4-4 NPK, for example – twice per year, but my soil is fairly rich. Sandier and less rich soils may require fertilizer up to four times per year, until you build up nutrient levels. Make sure not to over-fertilize as this can cause toxicity and lead to imbalances. Acquiring a home soil test kit or sending your soil off to a testing lab will give you an idea of how to balance nutrient levels with the right fertilizer.

Generally, hardy hibiscus requires a lot of potassium, only a bit of phosphorus, and a moderate amount of nitrogen in most soils. An NPK of 17-5-24, 9-3-13, or 10-4-12 may work to amend soil that is poor in all nutrients, for example. If your soil is low on phosphorus, this will reduce flowering.

In this case, give your plants a good organic-based liquid fertilizer that’s high in phosphorus in the spring to encourage blooming. Be careful not to overdo it, though – too much phosphorus will also reduce blooming, and can damage or even kill your plants.

Winter Care

In areas with wintertime temperatures below freezing, make sure plants have 3 to 4 inches of mulch to protect the roots over the winter. Wood chips, straw, leaves, and so on may be used effectively. Be patient in the spring, as hardy hibiscus is usually one of the last plants to come up, sending out its first new growth in May, or even June. Although hardy hibiscus doesn’t need to be pruned, to encourage more flowers, trim off growing stem tips when plants are 8 inches tall, and optionally, again at 12 inches.

Growing Tips

Keep well-watered until established Mulch well, especially during the hottest and coldest times of year Apply phosphorus-rich fertilizer in spring, unless soil is already high in this nutrient Protect from cold winds in cooler climates Although tolerant of wet soils, plant in well-draining soil and avoid waterlogged areas, which can cause root rot Full sun is ideal, though plants will welcome light shade in particularly sunny and hot climates

Cultivars to Select

As alluded to above, there are now many cultivars to choose from based on your climate, space availability, and aesthetic preferences.

Here are a few of the main ones to look out for. Here are a few of my favorite examples:

Kopper King

Hibiscus x ‘Kopper King’ has dark burgundy foliage with large, light pink to nearly white flowers that feature pink veining and burgundy throats.

Hardy in Zones 5-10, plants reach a mature height of 3-4 feet with a spread of 4-5 feet.

Lady Baltimore

Hibiscus x ‘Lady Baltimore’ has large, pink, dark-throated flowers with green foliage.

‘Lady Baltimore’ Tolerant of moderately moist to wet soils, they are early flowering and grow in Zones 5-10, growing 5 feet in height and width. Plants are available at Burpee.

Midnight Marvel

Hibiscus x ‘Midnight Marvel’ has large, deep red flowers with dark burgundy maple-leaf-like foliage.

‘Midnight Marvel’ Rounded plants with flowers from top to bottom grow in Zones 4-10 and reach 3-4 feet in height with a spread of 4-5 feet. Find ‘Midnight Marvel’ plants at Burpee.

Terri’s Pink

Hibiscus x mutabilis ‘Terri’s Pink’ grows 6 to 8-inch, red, saucer-shaped flowers blooming as early as late spring. As an infertile hybrid, it does not produce seeds. It grows in Zones 7-11 to a height of 6-8 feet and with a spread of 4-6 feet.

Managing Pests and Disease

Hardy hibiscus isn’t terribly susceptible to pests or disease, but they can have issues.

Herbivores

Herbivores aren’t generally a problem for these plants, though some people do report one pest as a potential problem:

Deer

In areas with deer pressure, deer browse can be a problem. A fence will help to keep them away. Learn how to build your own deer fence with our DIY tutorial.

Insects

Hardy hibiscus can suffer insect damage to both its leaves and flowers, and there are numerous strategies for dealing with these. My personal preference is to create a diverse ecosystem with predator habitat to encourage beneficial insect populations, and to employ integrated pest management. But sometimes, if you want to save a plant, treatment can’t be avoided. Some of the more common pests include:

Aphids

These little suckers suck – literally. The tiny black, brown, or white bugs are usually found on the underside of leaves or close to the stem tips, and on and around flower buds, drinking the plant’s juices while depositing their disease-spreading saliva. An insecticidal soap spray applied weekly until the insects are gone takes care of them. You can read more about dealing with aphids in the garden here.

Scale

Scale is a soft bodied sapsucker with no limbs, and it is related to aphids. These hide under rounded waxy scales on the underside of leaves. The species commonly affecting hibiscus is black scale, though other colors and varieties may be found too. Scale can also be treated with insecticidal soap. Read more about treating scale infestations here.

Whiteflies

Another relative of aphids, whiteflies spread rapidly if left unchecked and can be hard to control. As the name implies, they are small, white flies often found crowded together on the underside of leaves, sucking the plant’s juices. Neem oil-based insecticides can be used on the foliage, and affected leaves should be removed diligently and destroyed. Read our guide on whitefly control for more information.

Disease

Most diseases that affect hardy hibiscus are fungal. These plants may be susceptible to botrytis blight, leaf spot, and rust, all of which affect the leaves, as well as canker, affecting the stems and branches, and root rot. Aboveground fungal diseases can be prevented by avoiding splashing water on leaves when watering. A rust, leaf spot, or blight infection can be treated with a copper-based fungicide. Affected parts should be removed from the garden and not composted, but instead burned or otherwise disposed of away from your gardens to avoid the spread of the disease. The remaining leaves should then be sprayed. Removal of affected plant parts is the only way to prevent the further spread of canker. To prevent root rot, don’t overwater, and make sure the plant has good drainage.

Best Uses

Since most varieties tolerate wet – but not permanently waterlogged – soils, they do well near water features or in damp spots.

Larger varieties make an excellent late-season backdrop, while smaller varieties are wonderful specimen plants to draw attention near balconies or walkways.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

Bring a Touch of the Tropics to Your Late Season Garden

Late in the season when there are fewer flowers blooming, hardy hibiscus can add a brilliant boost of extravagant color to your gardens. Though known for its flowers, the hardy hibiscus has some beautiful foliage shapes and colors that add their own interest to your landscape as well, from deep green hearts to burgundy maple-like leaves.

What’s your experience with this plant? What varieties have you tried? Please share your successes, failures, and what you’ve learned in the comments below. And for more information about growing flowers in your garden, check out these guides next:

How to Grow Hyacinth Bean Vines How to Plant and Grow Lilies How to Grow and Care for Columbine Flowers

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Burpee. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Allison Sidhu.