You don’t get the chance to know and understand them as intimately as you would a plant that you care for year after year, such as a rose. They are here and then gone in just a few months. That is, unless you grow hardy fuchsias. Sure, those tender fuchsias that you can buy at the home supply store are gorgeous, but most of us end up tossing these perennials out at the end of the growing season. They can’t survive even a hint of frost, so it’s tough to keep them around for the long haul in most climates. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. These plants have different growing requirements than their tender siblings, and this guide aims to help you make them thrive as the showy perennial shrubs they were meant to be. Here’s what we’ll discuss to make that happen: If you’re ready to start the beginning of your beautiful friendship with hardy fuchsias, then let’s dig in.

What Are Hardy Fuchsias?

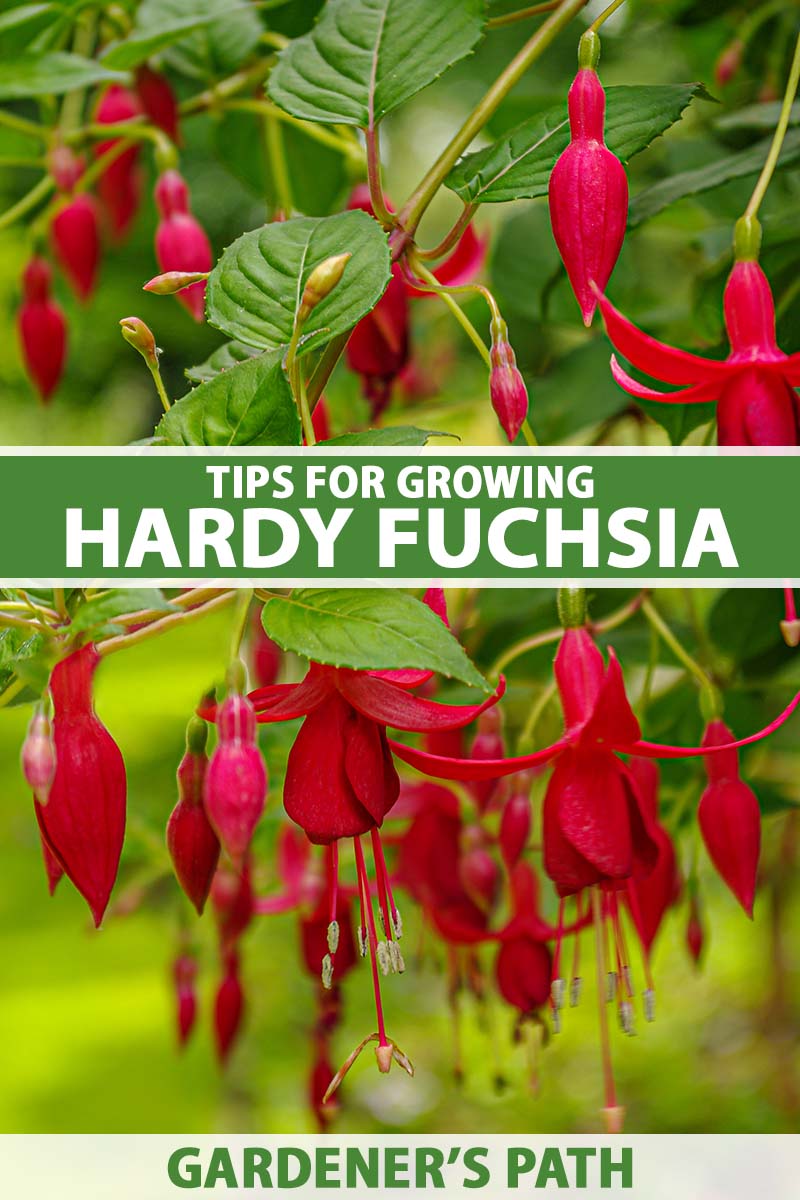

Before we jump into the growing tips and recommendations, we should be clear about what sets the hardy ones apart from “tender” fuchsias. Most people think of fuchsias as tropical or semi-tropical plants. While it’s true that most species grow natively near the equator, many grow at extremely high elevations in that area. F. dependens, for instance, grows at up to 10,900 feet above sea level in Ecuador. That means these plants are able to withstand much cooler temperatures than many gardeners realize. Hardy fuchsias have woody stems and usually, though not always, have more of a bush-type growth habit rather than the vining habit you commonly see in hanging types. They also tend to grow larger and, as their common name suggests, they can handle colder weather. As for those hanging fuchsias you can buy at practically every home supply store in the spring? They’re almost always a tender hybrid or species, though I can’t tell you how often I have seen them labeled as hardy. Just look at the tag. Is the plant labeled as Fuchsia hybrida? In that case, it’s probably a tender hybrid. You can be sure by checking the recommended USDA Hardiness Zone range. The reason there’s some label confusion here is that the term “hardy” isn’t officially defined according to any particular governing body that deals with plant descriptors. Usually, any variety of F. magellanica is called “hardy.” When people talk about hardy fuchsias, this is what they’re most often referring to – and in the case of this species, that descriptor is true. Growers group fuchsia into three categories: tender, half-hardy, and hardy. Tender plants can survive as perennials in Zones 10 and 11, half-hardy plants will thrive year-round in Zones 9 and 10 (and even in Zone 11 with some protection from the afternoon heat), and hardy species can grow outdoors in areas as cold as Zone 6 with some winter protection. By the way, if you purchased a fuchsia that isn’t hardy in your region and you want to keep it around, you can grow these plants indoors during the winter. In fact, you can grow them indoors year-round as houseplants, if you want. We have a guide that helps explain how to do it.

Cultivation and History

Most hardy fuchsias are hybrids bred from F. magellanica, which is native to Argentina and Chile. You’ll also see hybrids of F. arborescens, F. bacillaris, F. cylindracea, F. ravenii, F. thymifolia and F. encliandra. Collectively, these species are all referred to as Encliandra types, even though only one is technically named encliandra. These are usually hardy or sometimes half hardy. Hybrids of F. microphylla and F. obconica, meanwhile, can be half-hardy or hardy as well. Be sure to check the tag to make sure the plant you choose can handle temperatures down to 32°F if you’re looking for one that won’t die if freezing weather is in the forecast.

Propagation

Hardy fuchsias aren’t typically grown from seed, since most of these are hybrids. That’s okay, they’re incredibly easy to grow from cuttings. You can take either soft or hardwood cuttings. By the way, if you decide you want to try growing from seed, it can be done. Just keep in mind that the resulting plant might not grow true, meaning it won’t have the same exact qualities as the parent plant. But you can still grow interesting plants this way. We have an entire guide aimed at helping you to harvest and save fuchsia seeds if you’re interested.

From Hardwood Cuttings

Hardwood cuttings should be taken in the fall. One of the nice things about this method is that you get to wait until all of the leaves have already fallen off the plant – one less step you have to worry about! Take a foot-long cutting of hardwood and slice the bottom at a 45-degree angle. Dip the end in a rooting hormone powder or gel and place it in a four-inch round or square container filled with a seed-starting mix. Water so the medium feels like a well wrung-out sponge. Put the pot in a spot indoors where it receives six hours or so of indirect sunlight, not direct sunlight. Keep the soil moist. If you live in a dry climate, or if your home’s winter air is dry thanks to forced-air heating, you can mist the cutting every day or so with a spray bottle. Leave it in place until the spring, when you should start to see leaf buds forming. Once the soil is workable outside, you can transplant your rooted cutting to the outdoors. Just be sure to harden it off first. If you’ve never hardened transplants off before, the process is simple. Your goal is to give the plant gradual exposure to the outside world so it isn’t shocked by the transition. On the first day, put it outside in a sheltered spot for about an hour. On day two, add an hour. Keep adding an hour a day until the plant can stay outside for eight hours.

From Softwood Cuttings

Softwood cuttings should be taken in the spring when new growth has formed foliage, but before the flower buds open. Look for fresh, green growth at the end of a section of hardwood. Cut off about six inches at a 45-degree angle and remove all but the top two leaves. From there, follow the same steps described above for potting hardwood cuttings, but instead of spraying the cutting to provide extra moisture, cover it with a plastic bag if you live in a dry climate. Prop the plastic up with chopsticks or pencils to hold the bag away from the cutting. Keep an eye on the cutting. If it starts to look wilted despite having plenty of water, or if you see mold forming, remove the bag. Transplant once new leaves have formed, but again, be sure to harden it off first before putting the transplant outside. You might want to wait until the fall if the weather is particularly warm when the leaves have formed. Anything above 85°F is probably too hot for new transplants.

From Seedlings/Transplanting

When you plant your new fuchsia, it should be placed four to six inches deeper than it was growing in its container, but be sure to avoid putting more than half of the plant below the soil level. You do this to protect the roots and crown, which helps your new plant not only to survive colder temperatures, but warmer ones as well. Fuchsias don’t like hot roots any more than they like freezing ones. You’ll initially lose some of the height of your plant, but this will pay off in the long run when your fuchsia grows healthier and bigger than it would have if you didn’t give it the right start.

How to Grow

Hardy fuchsias growing in the ground are different from tender ones, and they have different requirements. It surprises many gardeners to learn that they need partial or even full sun, not shade. Of course, if you live in an area that gets extremely hot during the summer, you’ll want to plant them somewhere that they will be shaded from the heat of the afternoon. Ideally, you’ll choose a location that receives sun all morning long with some afternoon shade, and then a little additional sun in the evening. Avoid areas with reflected sun – it’s just too intense for these lovely bloomers. In more temperate areas like the Pacific Northwest or coastal northern California, full sun is ideal. Fuchsias growing in containers should be planted with a bit more shade, since they tend to dry out more quickly than those planted in the ground, and the roots heat up faster. Speaking of water, this is where you need to be diligent. Moisture is more important than sun exposure for the success of your plant. Hardy fuchsias can usually handle receiving a bit less water than their tender cousins, but they still need moist soil. The soil should stay moist at all times, though you can let the top inch dry out if your plant doesn’t show any signs of drought stress such as wilting, or leaf edges that are turning yellow or brown. If you find your plant is wilting, it’s probably not getting enough water. Feel the soil. If it feels dry, add water. If it’s moist, your hardy fuchsia is probably getting too much sun. You’ll need to move it, or provide it with shade if you’re having a rare heatwave. Moisture is one of the reasons that people tend to plant fuchsias in heavier shade than they need. It’s a lot easier to keep a plant moist when the sun isn’t beating down on it all day. While they can make lovely container plants, unless you’re growing one that is hardy to at least one USDA Hardiness Zone below where you live, they need to be grown in the ground. That means if your plant is hardy to Zone 6 and you live in Zone 7, you can grow your fuchsia in a container. You’ll want to provide it with some protection, either by covering it in pine boughs or moving it into a garage or shed for the winter. If you move them, make sure to give your plants some water now and then. You can allow the top two inches of soil to dry out before you add more water. If you plant a hardy fuchsia that only grows down to your zone (a plant that is hardy down to Zone 7 grown in a Zone 7 garden, for instance) in a container, you will have to treat it as an annual or bring it inside. It will likely die over the winter if left outdoors. That’s because these plants need a large, healthy root system to help them survive the cold. Plants with a healthy root system can actually die completely back to the ground during a harsh winter and they will return in the spring.

Growing Tips

Plant in full sun to partial shade.Soil needs to remain consistently moist.Use caution when planting hardy fuchsias in containers.

Pruning and Maintenance

Pruning is an excellent way to improve your hardy fuchsia’s appearance. You don’t need to prune yours necessarily, but as with most plants, a little pruning will keep them looking tidy and can help to discourage diseases. Pruning not only improves the plant’s shape and health, but it encourages more blossoms as well. While some plants produce blooms on last year’s wood, fuchsias produce blooms on the current year’s new growth. When you prune a woody perennial, this causes the plant to form new branches with new growth. If you cut your plant back in the early spring before it emerges from dormancy, you’ll create lots of new growth, and more flowers as well. There’s no hard or fast rule when it comes to pruning, but you should aim to remove any dead or diseased wood, and give the plant some shape. Thin out any dense areas in the center of the bush to discourage disease. I’ve seen some gardeners use hedge trimmers to give their plant a uniform shape. I prefer to break out the secateurs and be a bit more judicious about my trimming. Don’t trim your plant back more than a third at a time or you could risk shocking it. That said, this is one of those plants that I’ve trimmed back dramatically and it didn’t have any noticeable effect in my experience. Prune back up to a third of the plant in the spring before any of the leaf buds have opened, or in the fall after the foliage has all fallen off the bush. You can remove any dead or diseased branches throughout the year. Find detailed fuchsia pruning information here. Every six weeks throughout the spring and summer, give the plant an inch of well-rotted compost around the base, away from the stems. This acts as both mulch and fertilizer. If the mulch builds up too much, just remove the old stuff when you add new. In the first year or two, you might want to provide some winter protection in the form of mulch. Three inches of pine boughs, straw, or leaves should do it. Remove the mulch when the last projected frost date has passed.

Cultivars to Select

It’s hard to believe how many hybrids and cultivars of fuchsias that there are out there. It would be a hard task to describe all of the wonderful options that breeders have created. Instead, we’ll give you a few of the stand-out options that are more common to find at nurseries, but be sure to keep your eye out for the newer and less common fuchsias, as well.

Alice Hoffman

‘Alice Hoffman’ is a hybrid that grows in Zones 7 to 10 and is perfect for those small areas or containers because it tops out at two feet tall and wide. It blooms with bright pink and white flowers from early summer to frost.

Aurea

‘Aurea’ hybrid has vibrant green leaves with gold margins. The single blooms are bright red, bringing vibrant contrast to the leaves. It grows to about three feet tall and five feet wide, and thrives in Zones 7 through 10.

Charming

‘Charming’ truly is as such, with its large, three-inch-long blossoms in vibrant red and purple. This cultivar is hardy down to Zone 7 with some winter protection.

Encliandra

Encliandra fuchsias are dwarf-sized plants. The largest ones grow three feet tall and wide, but many of them stay closer to a foot tall and wide. These do best in partial shade, but if you live in a cool enough area, you can put them in full sun where they’ll stay compact. Plus, in full sun, they’ll be absolutely blanketed in flowers. These lend themselves well to topiary and bonsai. These can vary in terms of what Zone they’ll survive in, but most are hardy to Zone 7 or 8.

Hardy Fuchsia

F. magellanica var. gracilis, usually just called “hardy fuchsia,” is one of the most cold-tolerant fuchsias, thriving as a perennial all the way down to Zone 6. With pink and violet single blooms, each flower is long and thin, with an extremely long sepal and calyx. Plants top out at about 11 feet tall and six feet wide.

Hawkshead

F. magellanica ‘Hawkshead’ stands out with its petite, tubular, pure white flowers, a color that is extremely rare among fuchsias. When in full bloom, it looks like it’s covered in large icicles. Hardy to Zone 7, it grows to about three feet tall and wide with a bush-like growth habit.

Tricolor

‘Tricolor’ is an F. magellanica cultivar that has beautiful variegated cream and green leaves that start out maroon when young, but it’s the flowers that really make a statement. The sepals are white with bright green tips, and the petals underneath are neon orange. This bush grows to about five feet tall and three feet wide. It blooms all summer and is hardy down to Zone 7.

Versicolor

This F. magellanica var. gracilis cultivar has pink, red, and purple multicolored flowers, and gray-green leaves that have a hint of pink when they’re young. Three feet tall and wide at maturity, this bush will try its hardest to go back to its F. gracilis roots, which means you’ll see sports forming with bright green leaves. Cut them off when you see them, or the entire plant will eventually revert to this form. This one is a bit more tender, only to Zone 8.

Managing Pests and Disease

Unfortunately, the term “hardy” doesn’t refer in this case to hardy fuchsia’s ability to withstand pests or diseases. Though generally unbothered by insect infestations and infections overall, these plants are every bit as susceptible to the same issues that other species face. For a full rundown, read up on these in our general guide to growing fuchsias. Aphids are common insects that will feed on hardy fuchsia, but it’s rare that they cause enough of a problem to kill a plant. Read more about managing them in the garden in our guide. Gall mites can be controlled through pruning and with applications of insecticidal soap. Whiteflies, which are more common with indoor plants, can be killed with a mix of hydrogen peroxide and water. As for diseases, botrytis blight can result in aborted flower buds, but you can avoid it by watering at the base of plants instead of overhead, and pruning to improve air circulation. Damping off is a common issue that kills seeds, seedlings, or young cuttings. Learn more about it in our guide. Rust spreads easily and causes brown spots on the foliage. It can be controlled using a copper fungicide.

Best Uses

Hardy fuchsias are ideal for containers, as specimens in the garden, trained as a topiary, or as bonsai. You can find weeping and crawling forms, so they can be used in hanging containers or as groundcovers, though these are often hard to find. Hardy fuchsias also have particularly tasty berries and flowers if you’re hoping to nibble on your plant. But boy was I wrong! Once I found out there were hardy fuchsias that could survive some seriously cold weather, I never looked back. They became an important part of my perennial garden. I’m hoping our guide helped you discover the resilience of this showy bloomer. If so, I’d love to see pictures of your plants. Come back and show us how they’re doing in the comments below. Additionally, if you have fallen in love with fuchsias as I have, we have many more guides to help you on your growing journey, including:

Why Is My Fuchsia Wilting? 5 Common IssuesDo Fuchsias Need Deadheading?How to Prepare Your Fuchsia Plants for Winter