While they get more love in the UK than in the US, even there they take a backseat to their raspberry and blackberry brethren. It’s my mission to change that by the end of this article. Once we’re done, you’ll be singing the gooseberry’s praises from your rooftops. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Gooseberries suffer from a fraction of the pests and diseases that plague blueberries. They’re versatile and handsome in the garden, but unlike some other fruit plants, they’re pretty low maintenance and don’t take up too much room. And sure, not all varieties have that honeyed sweetness that other fruits boast, but they have a tart ambrosia all their own. While we’re on the topic of the fruits, they don’t rot as rapidly as many others do after harvest, so you can keep them around a bit longer after you’ve plucked them for use in desserts, yogurts, and jams. On top of that, they make pretty ornamental additions to the garden. You can train them up walls or use them as a natural fence.

While the flowers are generally not too showy, they attract bees and butterflies. In the fall, the leaves turn a lovely, vibrant red. Convinced you need this oft-undervalued contribution to the edible landscaping world? Then let’s dig in.

What Are Gooseberries?

Gooseberries belong to the Ribes genus, along with currants. While currants have small berries that grow in clusters, gooseberries have larger fruits that grow individually along the stem.

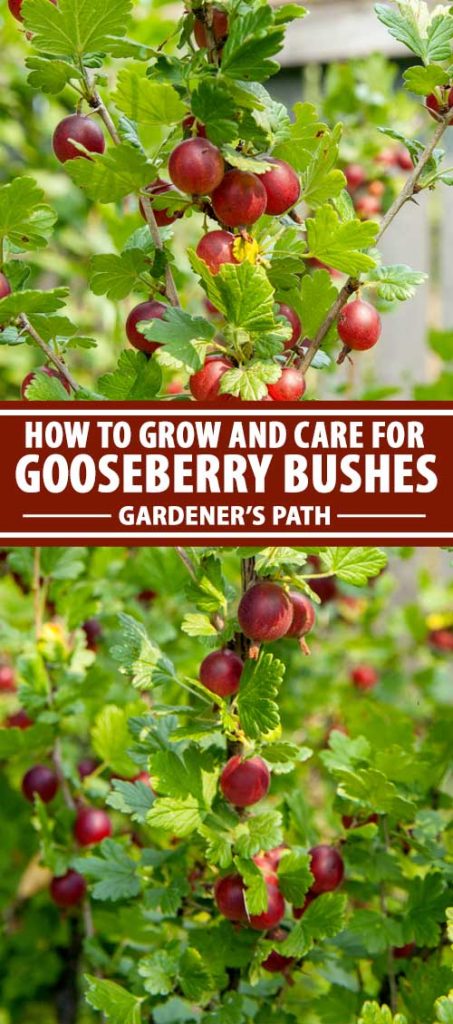

Unlike currants, which are quite tart, gooseberries can range from sweet to mildly tart. They should not be confused with the Indian gooseberry, Phyllanthus emblica, which is unrelated. Gooseberry plants have thorns, which makes them a pain in the… hand to harvest. Cultivated gooseberries come in two main types: American (R. hirtellum) and European (R. grossularia var. uva-crispa). The European species is native to North Africa, eastern Europe, and western Asia. The North American variety can be found across the northern regions of the US and southern areas of Canada. Generally, European types are thought to taste better, with a stronger flavor and larger fruit. However, some modern cultivars are challenging that notion.

North American varieties are more resistant to diseases and typically more productive. They can also grow in warmer, sunnier areas than the European types. The berries of both types range in size from 1/2 inch to an inch in diameter and come in a range of colors including light green, yellow, pink, red, maroon, and deep purple. They’re sometimes covered in fine hairs. European plants have deeply lobed, glossy, dark green leaves. American types have pale or gray-green leaves.

Both types reach about five feet tall and six feet wide at maturity, and most of them have thorns. The plants can handle some intense cold, with a few varieties growing happily even in USDA Hardiness Zone 2. Most cultivars grow best in Zones 3-8.

Cultivation and History

Gooseberries have been cultivated in the UK since at least the 1400s, and in the US since the 1800s. Growers in the States started by crossing native plants with European varieties. In parts of England, there used to be dozens of clubs aimed at growing the largest, tastiest berries. Most of these older cultivars have disappeared, but a few persist today. Perhaps part of the reason these berries aren’t very popular as a modern-day fruit is that they were banned by the Federal Government in 1911, along with currants. Both plants can host white pine blister rust, which can impact all types of five-needled pine trees. The timber industry lobbied to have the plant banned, and the ban stayed in place until 1966.

Now, it’s up to individual states to decide if they’ll allow gooseberries. These days, a few areas in the Northeast limit or prohibit growing them. These areas include parts of New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Maine. While you could serve gooseberries with a cooked goose, and this association may be the reason for its name, the name is also thought to come from the German word Krausebeere. It may also come from the French word for currant, groseille.

Propagation

You can grow them in containers, train them up a trellis or against a wall, or plant them in the ground in the garden. You can also prune these small shrubs into standards – or small trees – to enhance their ornamental appeal.

Gooseberries develop side shoots that produce fruit, which allows them to be trained up trellises or along walls. Trellising can help increase air circulation, which reduces the chance that your plants will contract a fungal disease. They also work well as a thorny barrier in the garden or at the base of a downspout, since they love water. Just make sure the soil is well-draining. They don’t do well with wet feet. Plants are self-pollinating, so you don’t need multiples in the garden unless you want lots of fruit. Growing multiple plants tends to increase your berry harvest.

Gooseberries can happily grow in part shade and they prefer a cool, moist spot. If you live in a warm climate and you’re looking to fill in that area of the garden with a northern exposure that gets only three hours of sun per day, this plant is a good candidate. That said, if they get closer to six hours of sun a day, you’ll get a larger harvest. The challenge is that the leaves can get sunburn and collapse quickly when temperatures rise to above 85°F, so you may need to protect them from the midday heat, depending on where you live. You can do this by planting in a location that gets a little afternoon shade, and some mulch to keep the roots cool. An eastern exposure is ideal, with a bit of protection from high winds. Water spreads disease, so it helps to keep any moisture on the plants to a minimum. You should also avoid planting in potential frost pockets like those that may form at the base of a hill. Organically-rich, well-drained soil is preferred. In the fall before you intend to plant, clear out all the weeds and amend the soil, if needed. You’ll need to do a soil test to determine what type of fertilizer, pH adjustments, and other types of amendments you’ll need. While gooseberries aren’t too fussy about the soil they’re growing in, they can’t handle sandy soil because it dries up too quickly. If you have sandy or heavy clay soil, work compost, peat, or manure into the soil at planting time. Plants need a pH of 5.5-7.0 and they should be planted four to five feet apart to provide enough room for their mature spread.

By Transplant

Starting with transplants from a reliable source is important because it helps to avoid diseases that can take out your crop. If you live in a warmer area, you can plant out in the fall, typically in October. Otherwise, they’re best put in the ground in the spring. Plant as soon as you can work the soil. Even young plants can handle a heavy frost. The key is to keep the roots moist and cool until you get them in the ground. Soak the roots for four hours before putting them in the ground. Loosen the root ball and cut away any dead roots. Trim back the tops of the plant to about six to 10 inches. This encourages new growth. Dig a hole that’s an inch deeper and twice as wide as the container they came in.The goal of setting these plants a bit deeper is to encourage basal branching. You may want to check with your local nursery for recommendations regarding planting depth, since different varieties have different depth requirements. Once you’ve gotten your new plant in the ground, water it in well.

From Cuttings

If you have access to a North American gooseberry bush, take a foot-long cutting from a cane that is at least a year old in the late fall. The bottom cut should be just below a bud and the top cut should be about an inch above a bud. Set the cutting outside in soil – bottom cut side down – with a third of the plant buried under the earth. Cover with straw so just the tip is showing. You can also take a cutting in early spring before the leaf buds emerge. European varieties don’t do as well when propagated via cuttings. Instead, you can layer them.

By Layering

You can also propagate gooseberries through layering. In the spring, bend down a healthy, low-growing branch. If you know you’re planning to do this when you’re pruning, you can leave a low-growing branch in place just for this purpose. Cover several inches of the branch with soil and secure it in place using a stone or brick. In the fall or the spring the following year, clip off the exposed branch and dig up the new plant, which should have formed several branches, leaves, and roots. Dig about eight inches deep and 12 inches wide to ensure you’re getting the entire root structure. Then, plant as you would a transplant.

From Seed

If you can’t find a plant at a nursery or you are unable to take a cutting from a friend, you can grow gooseberries from seed, though it takes a bit of time and effort and they don’t grow true. Starting these plants from seed isn’t recommended, as hybrids will not produce true to the parent plant. If you do choose to sow seeds, you’ll need to pick the seeds out of the fruit using a pair of tweezers. Soak the seeds in room temperature water for four hours and then dry them completely. Put them in a soilless seed starting medium and place them in the refrigerator for three to four months to cold stratify. Don’t let the medium dry out. In the spring, sow them in your prepared bed by poking holes 1/2-inch deep, and cover with soil. Keep them moist until seedlings emerge. Thin the plants out to four to five feet apart once they’ve developed three or four sets of true leaves.

How to Grow

In the first year, don’t let the plant flower or produce any fruit. Rub or pick off any blossoms that you see in the spring. In the second year, you’ll get a small harvest. By the third year, you should be getting a full crop.

Add a year to all these approximate times if you grew your plants from seed. Keep plants well watered with an inch of water a week. If the local precipitation doesn’t do this for you, add supplemental irrigation (this is where a rain gauge comes in handy!).

Fertilize with a balanced 10-10-10 (NPK) fertilizer every three to four years in the spring, according to package instructions. You want to avoid giving the plants too much nitrogen because this can cause leaf growth at the expense of fruit. This abundant growth can also be vulnerable to powdery mildew, which is the enemy of gooseberries. Mulch with straw, grass clippings, or bark chips. You want to lay down about two or three inches of mulch to help retain moisture and to prevent weeds from growing. Gooseberries have shallow roots, and they don’t do well when they have to compete with weeds. In the early spring of the second year, you’ll want to pick five or six of the largest, most robust canes to keep in place, and prune out everything else. Like many types of berries, these plants need to be pruned regularly if you want them to be as productive as possible. That’s because the two- and three-year-old wood produces the most fruit. When you get ready to do this job, you should find yourself a suit of armor, or at least a chainmail shirt that goes to your wrists. All kidding aside, the thorns on these plants are no joke, and they make it difficult to prune. When you get down and dirty, you need to make sure your hands and arms are covered. Don’t wear a jacket that you cherish, because the chances of getting a rip or two… or three or four… is high. In the late winter or early spring while the plant is still dormant, get the pruners and gloves out. In established plants, you should remove any canes that are over four years old. Also, remove any branches that are growing too close to the ground to help prevent disease. Remove any canes that are crossing each other and any that look diseased or broken. Keep a total of about a dozen canes at any one time, with half of them being new shoots and the other half a mix of two- and three-year-old canes. To remove a cane, clip it at the base of the plant using a sharp pair of pruners. In the end, you should have about 12 canes left.

Because they bloom early in the year, the blossoms can be damaged by late frosts. This will ruin the year’s harvest. Keep an eye on the weather report while the plants are blooming, and cover bushes with a tarp or cloth to protect the blossoms if frost is in the forecast.

Growing Tips

Keep moist with an inch of water a week Prune annually Protect plants from late frosts or temperatures above 85°F

Cultivars to Select

In the US, most cultivars are American species crossed with European varieties to improve the size and flavor of the berries while retaining the disease resistance. Your first line of attack is to purchase from reputable sources to make sure you’re getting disease-free plants.

Black Velvet

This North American variety has large purple-red fruits with an incredibly sweet flavor reminiscent of blueberries. ‘Black Velvet’ can handle a bit more shade than some other varieties.

‘Black Velvet’ Expect a mature height and spread of three to five feet. Plants are available at Burpee.

Captivator

This North American type has large, sweet, red fruits. It also has fewer spines than some other varieties. Like other American types, ‘Captivator’ is resistant to powdery mildew.

‘Captivator’ This cultivar grows to a mature height and width of two to three feet. Plants in 2.5-inch pots are available from Walmart.

Hinnonmaki Red

This popular North American variety features sweet, sugary, flavorful maroon fruits wrapped in a tart skin. This is one of the more vigorous types, and it’s not unheard of for them to fruit in the first year – but resist the temptation to allow them to do so while your plants are becoming established.

‘Hinnomaki Red’ Plants reach a mature height of three to five feet tall with a similar spread. You can find ‘Hinnomaki Red’ plants available at Nature Hills Nursery.

Jahn’s Prairie

‘Jahn’s Prairie’ produces an abundance of large, sweet red-pink colored fruits. This cultivar is named after Dr Otto Jahn, who discovered it in the Red Deer river valley, in Alberta, Canada in 1984.

‘Jahn’s Prairie’ Plants have an upright growth habit, with a mature height of four feet tall, and a similar spread. Find ‘Jahn’s Prairie’ in 2.5-inch containers available at Walmart.

Jeanne

‘Jeanne’ is an American variety with large, deep maroon berries. Once established, you can harvest up to three pounds of fruit from each plant. It’s resistant to white pine blister rust and powdery mildew.

‘Jeanne’ Mature plants grow to height and width of up to five feet. Plants are available at Burpee.

Jostaberry

This hybrid variety (Ribes x nidigrolaria) is a cross between a black currant and a gooseberry, with fruits that look like black gooseberries – and taste sweeter.

The plant doesn’t have thorns, grows rapidly, and is resistant to disease. This variety grows to a mature height and width of four to six feet.

Little Ben

For a prolific harvest on a compact shrub, consider ‘Little Ben.’ This cultivar produces sweet, pinkish-red berries with tart skin, ready for harvest in late summer. ‘Little Ben’ is a dwarf variety of ‘Hinnomaki Red.’

‘Little Ben’ Plants grow to a mature height of two to three feet, with a spread of three to four feet. Find a set of three bare root plants available at Home Depot.

Pixwell

This plant has small-to-medium blush pink fruit and a longer harvest season than most other varieties, producing for up to six weeks. It’s a popular North American variety with only a few small thorns.

‘Pixwell’ Plants grow to a mature height of four to six feet, with a spread of three to four feet. You can find ‘Pixwell’ plants for your garden at Nature Hills Nursery.

Managing Pests and Disease

A range of pests and diseases bother gooseberries, sadly. The good news is that, with the exception of mildew, most of these aren’t very aren’t common and may be managed easily. After that, it’s a matter of keeping an eye on your plants to monitor for signs of ill health or infestation, and being sure that they have good air circulation.

Pests

Of all the pests out there, birds will likely be your biggest foe. You should also watch for certain types of worms and aphids.

Birds

Birds love fresh gooseberries, and you can hardly blame them.

Your best bet for protection is to use bird netting to protect plants. But if you want to discourage birds and aren’t too worried if they sneak off with a few berries, you can spray your plants with Grape Kool-Aid or sugar water. Believe it or not, that sugary sweet purple drink is a deterrent to birds. It contains a compound called methyl anthranilate that birds hate. You can mix up four 0.14-ounce packets of unsweetened Kool-Aid with a gallon of water and spray it on plants when the berries are starting to mature. You can also combine five pounds of table sugar in with quarts of warm water and stir until it is dissolved. Then, spray plants that have set fruit. You’ll need to reapply both of these every few weeks, or anytime after it rains. You should also plan to use something else like scare devices or netting as additional deterrents if a large population of birds are attacking your plants.

Currant Aphids

Aphids are those all-too-familiar pear-shaped insects that like to hang out on the undersides of leaves, literally sucking the life out of your plants. The currant aphid, Cryptomyzus ribis, attacks gooseberries. Watch for cupping, distortion, and discoloration on plant leaves. You’ll also see the honeydew aphids leave behind accumulating. This honeydew can attract mold. The aphids themselves are brown and wingless for the first few generations, which start emerging in early spring, and then a generation with wings typically hatches out in the fall. Ladybugs are a natural predator. You can also blast plants with a strong stream of water from the hose to knock them away. Keep ants under control because they feed on the honeydew and can protect aphids from predators, enabling their populations to grow. You should avoid using pesticides if possible, because these can destroy beneficial insects as well as aphids. If you must, use an insecticidal soap according to the manufacturer’s directions. Learn more about protecting your crops from aphids here.

Currant Borers

While this insect is a bigger problem for currant plants, it can harm gooseberries, too. Look for the adults, called currant clearwing moths (Synanthedon tipuliformis). They have translucent wings with black bands. The body of the moth has yellow stripes. They lay eggs in late spring, and their larvae emerge shortly after to chew their way into the canes of the plant. Shoots may die, or they may emerge late the following year and be stunted. If you suspect you have this pest, snip an injured shoot. You’ll see a dark hole where the borer has moved along. Pruning is your best defense against this pest. If you have them, cut your entire plant back by a foot. You probably won’t have much of a harvest that year, but you’ll eliminate the borer. As you do your yearly pruning, remove and destroy any canes that you find that have dark holes in them.

Currant Fruit Flies

Currant fruit flies (Euphranta canadensis) are small flying insects that are about a third of an inch long (eight millimeters) and are beige, yellow, or orange. They lay their eggs on the berries of currant and gooseberry bushes and the larvae bore into the fruit and eat it from the inside out. If you examine your fruit and find maggots that look like grains of white rice buried in the middle of your berries, then E. canadensis is the likely culprit. After the affected berries fall to the ground, the larvae pupate and overwinter in the debris under the plant. Control methods include removal of the fallen berries and the leaves in which they hide. You can also use floating row covers before the adult flies become a threat. Organic pesticides such as pyrethrin work well against the adults – but will not reach the maggots buried in the fruit. Chemical insecticides have the same limitation. Read more about how to identify and control the currant fruit fly here.

Gooseberry Fruitworms

These worms are the larvae of the gooseberry moth (Zophodia grossulariella). They cause fruits to become hollowed out and discolored, and the fruits will fall off the plant prematurely. The adults are mottled gray and brown with an inch-wide wingspan. The light green larvae are about 3/4 of an inch long. You should handpick any worms you see and apply Bacillus thuringiensis to plants following the manufacturer’s recommendations as fruits start to form. Reapply after 12 days. Read more about using Bt in the garden here.

Gooseberry Sawfly Stem Girdlers

Stem girdlers are the larvae of gooseberry sawflies, Nematus ribesii. They are caterpillar-like worms, with a greenish-yellow body and black spots, between six and 12 millimeters long that feed on the leaves. Large enough populations can defoliate an entire plant . The first batch of these pests usually appears in mid- to late spring, and there can be two generations after that, so you need to keep an eye out all summer long. The adults have shiny black bodies and brownish-yellow legs. The female is about 1/2-inch long, while the male is slightly smaller. You’ll notice the shoots of your plant starting to wilt and eventually dropping off. The good news is, since the grubs only tunnel down about six inches, you can snip eight inches off the tip of each shoot to get rid of them.

Disease

R. hirtellum plants are resistant to powdery mildew and leaf spot. R. uva-crispa plants are generally more susceptible to these diseases, but you can find resistant cultivars.

Leaf Spot

Anthracnose, caused by the fungus Drepanopeziza ribis, isn’t as common as powdery mildew, but it’s more devastating. It causes brown spots on the leaves, stems, and berries, starting in early summer. The leaves may eventually turn yellow and drop, which reduces plant growth as well as the next year’s harvest. In the case of a severe infection, leaves may turn brown and fall off by midsummer. The disease lives on fallen leaves throughout the winter, so be sure to clean up any plant debris that has dropped around the base of plants in the fall. Keep plants well watered to help them survive the summer and reduce leaf drop. Choose resistant varieties if you know this disease is common in your area.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew, caused by Podosphaera mors-uvae fungi, is the most common issue you’ll have to deal with when growing gooseberries. Both American and European varieties can contract it, but R. uva-crispa is particularly vulnerable. This fungus looks like a white, powdery coating on the leaves, branches, and berries that eventually turns brown. It causes plants to be stunted and can kill new growth or cause berries to be small or cracked. It likes warm, humid conditions. Cut off any parts of the plant that are infected, and ensure you are giving your plant plenty of air circulation with regular pruning. Water at the base of plants, and do so in the morning so that leaves can dry out during the day if they get wet. You can use a sulfur-based fungicide if you get desperate.

White Pine Blister Rust

This disease spreads by spending part of the year on currants or gooseberry plants, and part of the year on five-needle pine trees. It doesn’t cause trouble for the berry plants, but it can damage susceptible pines. Keep gooseberries at least 1,000 feet away from any valuable pine trees, and do not plant in locations where they are forbidden.

Harvesting

Get the gloves and long sleeves out, we’re going harvesting. One plant can give you up to four quarts of berries a year. Depending on your location, harvest time usually begins any time from July to September. The fruits don’t ripen all at once – it happens over a four to six week period, so you will need to go out several times to pick everything. You can also leave ripe gooseberries on the bush for a week or two, since they don’t drop or get overly-ripe too quickly. However, if you just can’t wait, you can pick some of the green, under-ripe fruits to make jams, sauces, and pies.

Picking about half of the under-ripe fruits has the added benefit of allowing the remaining berries to get larger and sweeter than they may have otherwise. You can’t always tell when gooseberries are ripe by their color because different cultivars have different colors at maturity. They can be light green, pink, purple, red, or yellow when ripe. The skin will be translucent and they’ll feel plump and juicy when they’re ready.

The most foolproof way to know if it’s harvest time also happens to be my favorite method: pluck one off the bush and have a taste. Be careful as you pluck them, since extremely ripe berries can burst in your hands. You can also lay a tarp under the bush and gently shake and knock the ripe berries loose. And remember to wear gloves, to avoid being snagged by thorns!

Put the berries in a shallow container rather than a deep bucket, or use small containers, because gooseberries can get crushed by the weight of the other berries. With some care, gooseberry plants can keep producing for up to 50 years. Read our full guide on harvesting gooseberries here.

Preserving

Gooseberries keep in the refrigerator for up to two weeks in a container. Don’t wash them before putting them away.

Pick off the little dried flower that sometimes sticks around on the blossom end of berries before eating. These won’t hurt you, but they don’t taste good. You should also snip off any stem portions that comes off when you pick the berry. To extend your harvest, freeze the berries. Wash them and place them on a tray in a single layer. Freeze them and then place the frozen fruit in a sealed bag or container to keep in the freezer for up to two years.

Pickled gooseberries are a treat. You’ll need white wine vinegar, sugar, and washed berries. Fill a sterilized jar with a cup of berries and bring 2/3 cup of vinegar and 1/3 cup sugar to a boil until the sugar dissolves. Allow the sugar mixture to cool before pouring it over the gooseberries. Seal the jars and store in the fridge. After a month, the pickle is ready to use. I also like to toss in some fresh ginger, cloves, and/or cinnamon sticks into the mixture, but they’re delicious without additional flavoring as well. You can learn about making jams and jellies on our sister site, Foodal.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Gooseberries are high in fiber and have a flavor that is sometimes compared to rhubarb, with less bitterness. However, some varieties are more sugary than others, and some are downright sweet when ripe.

Since they aren’t as beloved in the US as they are in the UK, recipes are more common in British cookbooks. You’ll see gooseberries in all the usual places: in pies and other desserts, in yogurt, or made into a jam. But I like to get creative. Because they have a bit of tartness to them, they make a nice addition to savory dishes. Every summer when the gooseberries are ready, I like to combine them with a little bourbon and diced cucumber to top grilled lobster or crab.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

Get to Know This Underappreciated Plant

Hopefully by now you’re a gooseberry convert! It’s time that these piquant fruits got the attention they deserve. I remember the first time I bit into a ripe berry and felt it burst in my mouth – it was a revelation.

With more gardeners growing these plants, more people will be able to experience all that gooseberries have to offer! Let me know if you run into any issues and what varieties you decide to grow in your space. While you wait for your gooseberry harvest to ripen, check out these other berry plants that you can grow at home:

How to Grow and Care for Boysenberry Bushes How to Grow Elderberries in Pots and Containers How to Grow Raspberries: Enjoy Berries for Years to Come

Photos by Kristine Lofgren © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Burpee, Home Depot, Nature Hills Nursery, and Walmart. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.