These woody, perennial shrubs aren’t the same thing as quince fruit trees. Both belong to the rose family, Rosaceae, but fruiting quince trees are the sole members of the Cydonia genus. Flowering quince, on the other hand, refers to species in the Chaenomeles genus. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Suitable for cultivation in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 9, these attractive plants are one of spring’s earliest harbingers. Are you ready to grow one or more of these beauties in your own yard? Let’s get started! Here’s what I’ll cover:

What Is Flowering Quince?

While it’s not the same plant as fruiting quince, some varieties of flowering quince actually do produce edible fruits in the fall, which the birds in your backyard will appreciate.

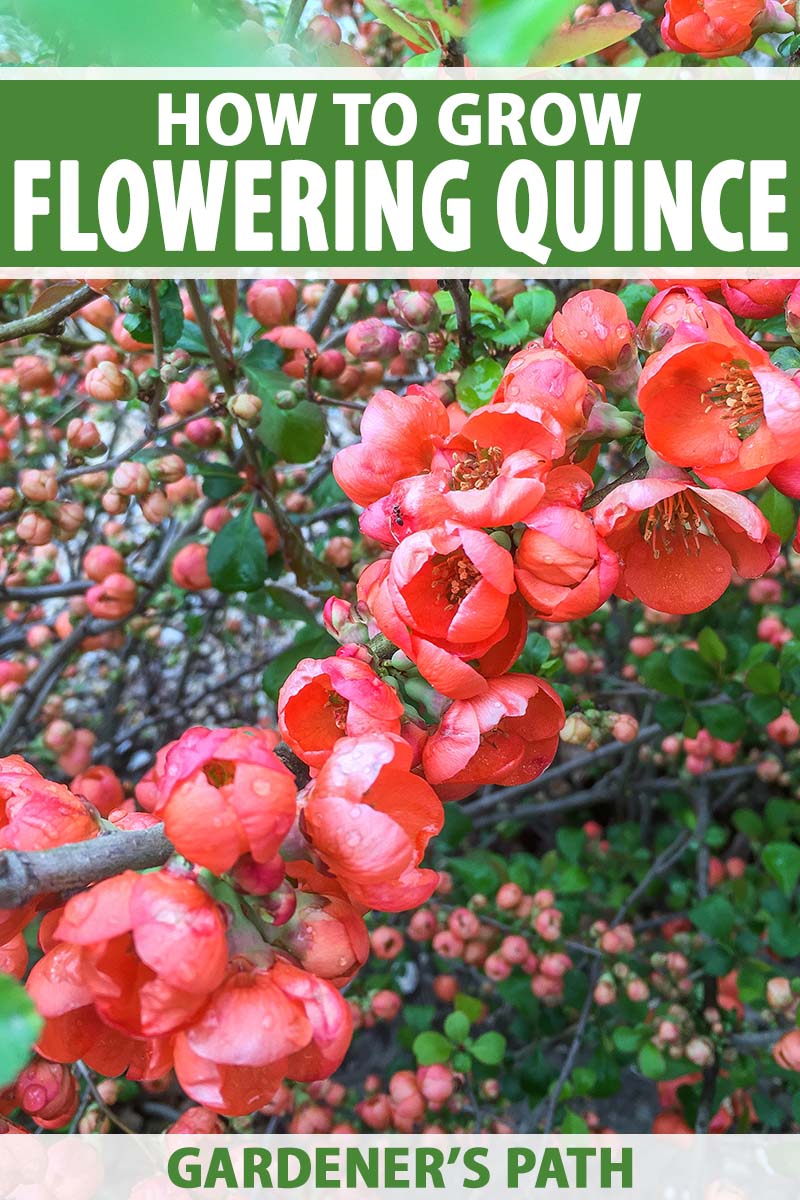

The aromatic fruits resemble apples and are typically small and hard, with a bitter taste. But they contain plenty of pectin, which makes them ideal for jams and jellies – as long as you add lots of sugar during the cooking process! But the standout feature of these shrubs is the profusion of glorious flowers in various shades of pink, orange, and red, along with pure white. The three flowering quince species are: C. cathayensis, aka Chinese flowering quince, grows and spreads up to 10 feet and bears fruit that’s nearly six inches in diameter. Native to China, Bhutan, and Burma, this species has light-pink and white flowers and is hardy in Zones 4 to 8. C. cathayensis is less commonly available to home gardeners than C. speciosa and C. japonica. C. speciosa grows and spreads four to 10 feet high and wide, bears red, pink, orange, or white blossoms in early spring on branches that grow in an arching, vertical fashion. C. japonica, or Japanese flowering quince, grows to just two to four feet in height and width and produces shades of red, salmon- and orange-hued blooms on outward-arching branches.

C. speciosa and C. japonica are both native to east Asia, including China, Japan, and North and South Korea, and have naturalized in much of the eastern half of the United States, as well as in Oregon. Cultivars that reliably produce fruit include C. speciosa ‘Apple Blossom,’ ‘Toyo Nishiki,’ and C. japonica ‘Texas Scarlet.’ After the first flowering in spring, some varieties rebloom in the fall, giving you an extra dose of color just before winter sets in. The leaves are one and a half to three and a half inches long and one inch across, with blooms that grow to about one and a half inches in diameter, depending on the variety.

Flowering quince grows in a sprawling fashion, somewhat like boysenberries and other cane bushes, and some varieties are so prone to tangle that if you don’t prune the branches every year the shrub can turn into an unsightly mess. The branches are thorny, so you probably don’t want to line your walkways with this shrub. But planting it under your windows or as a security hedge creates a spiky deterrent for potential intruders. The many cultivars of Chaenomeles species are available in various sizes, colors, and petal configurations. Some, like ‘Chojubai,’ are adorably attractive when trained as bonsai trees. Some feature single-flowered blooms while others dazzle with gorgeous double-flowered blossoms. Are all worth getting to know, and we’ll include three of our favorite varieties below.

Propagation

While you can grow flowering quince from seed, the seedling takes a long time to mature into a full-sized shrub, and germination can be a bit hit or miss. In the case of hybrid varieties, seeds will not produce true to the parent plant.

Most of the time, gardeners propagate flowering quince by tip layering or from stem or basal cuttings. The easiest way to get started is to purchase an existing shrub from a nursery. You can learn more in our guide to propagating flowering quince. (coming soon!)

From Seed

If you do collect seed from an existing plant, they’ll need to be cold-stratified before you sow them. To do this, place then in some peat moss or soilless potting mix in a refrigerator for three months. You can even pick fruits one year, place them in a sealed bag in the fridge for three months, and then remove the seeds from the fruits when you’re ready to sow them. Start them indoors in pots or flats in a seed starting mix that is well draining. Keep the soil evenly moist but not waterlogged until germination, which can take up to six weeks.

Tip Layering

If you have an existing shrub, tip layering is an easy way to propagate new plants. This method is often used to propagate cane plants, such as boysenberries. In spring, when the plant is actively growing, select a long, flexible branch that will bend down to the ground without breaking. Dig a three-inch-deep trench, and remove the leaves from the six to eight-inch section of stem that you will bury.

Bury the section of stem, leaving the branch connected to the mother plant. You may need to weight it down with a brick or use landscaping pins to keep the branch in place. Water well, and keep the soil evenly moist until it takes root. After about six to eight weeks, you can gently move the soil and check whether the stem has rooted. If you see evidence of roots, you can cut the branch away from the mother plant, and dig up the newly-rooted plant for transplanting elsewhere.

From Basal Cuttings and Suckers

Propagating flowering quince from basal cuttings is a lot easier than doing so from stem cuttings. It can be done at any time during the year. Plants also produce suckers, which can be dug up and transplanted. To take a basal cutting, locate a young, new stem at the base of the plant and carefully dig it out, leaving as much of the root system intact as possible. Plant the basal cutting or sucker in a container that’s at least six inches deep, in a well-draining potting mix and keep it moist until you see new growth.

How to Grow

Select an area in your yard that receives full sun or part shade. If you live in a windy location, choose a spot that’s a few feet away from a wall or fence to give the shrub a windbreak.

Strong winds can snap the branches, particularly those of young shrubs. And don’t forget to be mindful of the thorns when you choose your location. Flowering quince requires well-draining soil that’s organically rich, with a slightly acidic pH of between 5.0-6.5. You can conduct a soil test before planting if you wish, and amend accordingly. Mature flowering quince can tolerate dense soil, but if your garden has a lot of clay, you’ll need to amend it with some well-rotted compost and topsoil to loosen it up, and improve drainage.

For a show of spring flowers, new shrubs are best planted in the winter, when they’re dormant. To transplant, dig a hole twice as wide as the root ball and as deep as the nursery pot. Place the plant inside the hole and backfill with soil. Water thoroughly. For the first year, while your young plant is becoming established, you’ll need to water your shrub when the top half-inch of soil dries out. After the first year, you’ll only need to water the plant when the top inch of soil is dry. It’s pretty drought tolerant when established, but you can spread a thin layer of mulch over the planting site to help retain moisture during dry spells. Well-draining soil is important, because this shrub does not like wet feet. You only need to feed your flowering quince once a year, in late winter or very early spring just before flowers appear. Use a balanced, 10-10-10 (NPK) fertilizer and apply according to package instructions.

Smaller varieties of flowering quince can be grown in containers. You’ll need to choose a container that’s large enough to accommodate the mature dimensions of your plant – so be sure to read the nursery tag when purchasing! As a rule of thumb, when transplanting into a container, select one that’s approximately eight to ten inches wider than the current pot it’s growing in, to allow for root development. Ensure that your chosen container has adequate drainage holes in the bottom, and fill with potting mix, amended with perlite or vermiculite to improve drainage. You’ll need to be a bit more vigilant about watering, as soil in containers dries out quicker than it does in the garden – but beware of oversaturating your plant, as it really won’t tolerate wet feet!

Growing Tips

Plant against a wall or fence to provide protection from the wind Make sure soil is well-draining Feed once a year with a balanced 10-10-10 NPK fertilizer

Pruning and Maintenance

Once established, flowering quince shrubs are easy to maintain. Larger varieties can grow up to 10 feet tall, and these will require yearly pruning to keep in check and prevent them from becoming a thorny, tangled mess. In the case of some cultivated types and Japanese flowering quince, C. japonica, all you need to do is remove dead, broken, or diseased branches each fall. The shrub flowers on old wood, so the best time to prune is in late spring after the flowers have faded and dropped to the ground.

You’ll need to put on a pair of sturdy gloves, and wear long sleeves to protect your hands and arms from the thorns. You may even want to wear safety glasses or goggles to protect your eyes. Find the oldest branches – they’ll be darker than the new wood – and cut one third of them all the way down to the ground. Remove a few branches from the interior portion of the plant, too, in order to maintain adequate air flow between the branches. This also helps the sun reach the inner part of the shrub, and prevents it from becoming too dense.

Cultivars to Select

While there are several cultivated varieties to choose from, here are three of our favorites for you to enjoy in your yard.

Managing Pests and Disease

While flowering quince aren’t prone to disease and pests, there are a few issues to watch out for. This C. speciosa cultivar is hardy in Zones 5 to 9 and grows up to five feet tall and wide – and no higher. If you hate pruning, you’re in luck: Double Take Pink™ doesn’t need a yearly haircut! And if you don’t want to deal with fruits and the wildlife they attract, you’re doubly lucky as this cultivar does not produce fruit.

Double Take Pink™ The flowers are purely for show, and after the initial spring bloom there’s often a rebloom in the fall. You can find Double Take Pink™ available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Chojubai

If you don’t have room for a thick hedge but want the appeal of ruby-red blooms, ‘Chojubai’ is the dwarf cultivar for you. The non-fruit-producing flowers are just one inch across, and the leaves are just half an inch long, making for a perfectly to-scale miniature tree that grows to a mature height of about two feet tall. This is a cultivar that’s hard to find, but it grows readily from cuttings and thrives in Zones 5-9. You can grow it in a container and let this C. japonica cultivar brighten your patio or porch garden! This variety is also popular for growing as a bonsai tree, if that’s your thing.

Texas Scarlet

For an exuberant display of salmon-pink, single-flowered blossoms, look no further than ‘Texas Scarlet,’ a C. japonica cultivar that attracts birds and butterflies to your early-spring yard.

‘Texas Scarlet’ It produces small, astringent fruits that the birds simply adore. This cultivar is hardy to Zones 5-9 and grows and spreads three to four feet tall and wide. Plant several shrubs three to five feet apart to create a prickly yet pretty hedge. You can find plants in #3 containers available via Nature Hills Nursery. Thanks to the thorns, these shrubs are deer-resistant, although rabbits may nibble on younger plants. Diseases are uncommon, but there are a couple that can be a real threat to the plant’s health if not taken care of.

Insects

Flowering quince doesn’t usually have tons of insect problems, but aphids (of course) love to feast on new growth. If you see any of the small, pear-shaped insects on the plant, spray them off with a blast of water from the hose and apply neem oil or insecticidal soap, according to package instructions. Learn more about how to manage aphids in the garden here. You also need to watch out for various scale insects. These can be hard to spot because they look a bit like fungus collecting on the branches, or like a line of brownish or grayish scabs or galls.

The primary hosts for this fungus are juniper bushes or cedar trees, and it spreads by wind. Cedar-quince rust causes swollen galls on flowering quince branches. If you notice an infestation, you can spray horticultural oil, like Bonide All Seasons Horticultural and Dormant Spray Oil, available via Arbico Organics on your flowering quince according to package instructions.

Bonide All Seasons Horticultural and Dormant Spray Oil Spider mites can sometimes cause trouble, too. If you see small dark-brown spots on the undersides of the leaves, spray them away with water and apply neem oil to the affected area.

Diseases

If you notice dark green lesions on the leaves that turn a dark rust color over time, your flowering quince might have apple scab, an infection caused by the fungus Venturia inaequalis. The fungus overwinters in plant debris, and typically strikes in warm, wet weather. As the name suggests, it also affects apple trees. You can manage infections by spraying infected plants with BioSafe Disease Control spray, available from Arbico Organics, according to package instructions.

BioSafe Disease Control Another pernicious ailment is cedar-quince rust, caused by the fungus Gymnosporangium clavipes.

The galls can stay on the branches indefinitely and the fungus will infect the rest of the plant over time, which may result in a loss of blooms and fruit. If you see the galls, cut off the infected branches and dispose of them in the garbage can, then spray the plant with copper fungicide.

Best Uses

You can grow flowering quince as a security hedge along a fence, or as part of a mixed planting in perennial beds and borders, for early spring color. When you see the first buds form, trim off a few budding twigs to bring indoors and put into a vase filled with fresh water. The warm air will force them to open, and they’ll last a little bit longer than they would outside.

C. speciosa varieties make wonderful espaliers, as well. If you grow a cultivar that bears fruit, you can either leave the fruits for the birds or try your hand at making quince jam. Check out this guide to making jams and jellies on our sister site, Foodal, to help you get started. It’s a low-maintenance shrub that provides an early pop of much-needed color in the springtime, attracting bees and other pollinators to your garden. And some varieties will even produce edible fruit, which the birds will appreciate, even if you don’t!

Have you ever grown flowering quince? We’d love to hear your stories and questions in the comments section below. And to learn more about growing ornamental shrubs in your garden, check out these guides next:

How to Grow and Care for Winterberry Holly 23 of the Best Variegated Shrubs for Your Landscape Why Autumn is the Best Time for Planting Shrubs

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Arbico Organics, Hirt’s Gardens, and Nature Hills Nursery. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom.