The particular weave used to craft linen fabric, combined with the fiber’s inherent qualities including high absorption rate and heat conduction, render the textile well-suited for use in summer clothing. But the specific plant whose stalks are used to create linen — L. usitatissimum aka common flax, or linseed — is just one of about 200 plants in the Linum genus, which is part of the flowering plant family Linaceae. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Want to grow your own? Let’s take a look at specific varieties, where to find them, tips for helping your plants to reach maturity and harvest, and things to look out for.

Eat, Wear, or Massage into Wood: Grow Annual L. Usitatissimum

At one time, common flax was a major crop in the United States, grown in almost every state east of the Mississippi, according to the Iowa State University Extension and Outreach department.

The plant was grown not only for its fibers for fabric, but also for linseed oil, which is used to preserve wood — as in tabletops or cutting boards. Though its importance as a commercial crop has been reduced in the United States, it is still grown here for its fibers, its oil, and its seeds, which are often consumed for their potential health benefits.

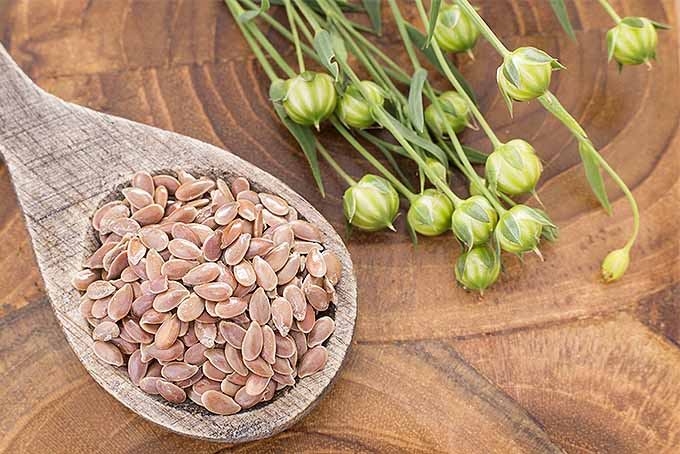

The brown or yellow/golden seeds contain a large quantity of omega-3 fatty acids, fiber, thiamine, magnesium, potassium, and phosphorus. Ground, it serves as an excellent substitute for eggs in vegan baking. (If you’re interested, you can read more about this on our sister site, Foodal.)

Planting Tips for Growing Edible Seed and Where to Buy

This annual plant — which has a tall, thin-stemmed growth habit similar to that of wheat — can also be grown in the home garden.

Similar to the way it is grown commercially, many backyard gardeners grow L. usitatissimum very densely, about 40 plants per square foot.

Harvest Time!

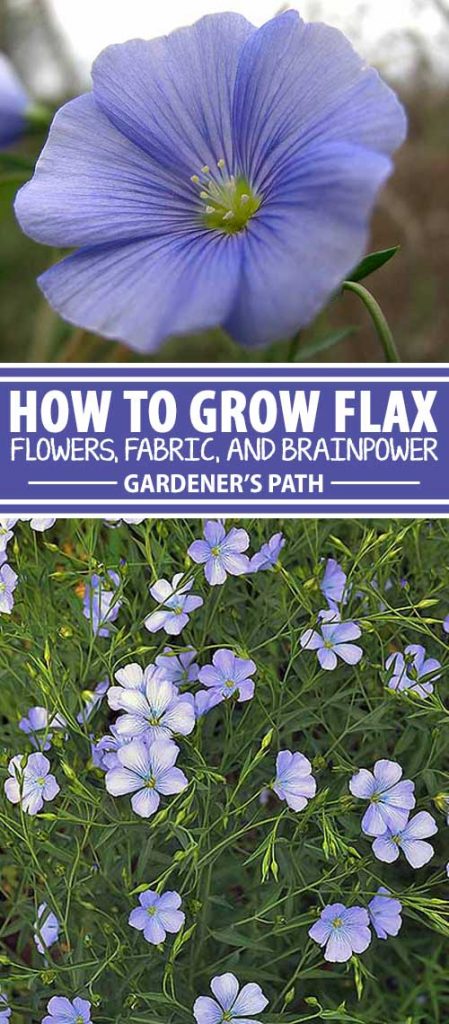

When the plant gets to its mature height of 2.5 to 3 feet, it continuously produces short-lived light blue flowers. 50 L. Usitatissimum Seeds You’ll get 50 GMO-free, organic seeds. Flax likes full sun and cool weather, and you’ll sow your seeds outdoors as soon as the fertile soil is workable, and when you know temperatures will remain above freezing. The seedlings can be sensitive to spring frost. To make them easier to spread, mix the seeds with flour. Then sow one tablespoon of seeds per 10 square feet, scattering them evenly across the soil. Rake the seeds down into the soil, to 1/4- to 1/2-inch deep. Each flower then develops into a pea-sized seed capsule. Each capsule contains four to 10 seeds. A boost in nitrogen amendments to the soil can help to increase seed yields.

You’ll know they are ready for harvest when the seed pods rattle when the plant is shaken. You can lightly crush the pods to release the seeds, or you can vigorously shake the cut stems onto a cloth to shake out the seeds. If you are growing flax for its fibers, you’ll need to harvest about a month after the plant begins flowering, before the seed pods form – which means you have to decide whether you’re growing for fiber or for seeds.

This isn’t an easy process, and it’s rather rare among home gardeners. A wet fall climate is also a requirement for processing, or retting, the fibers, so growing for linen production can only be done in certain regions. In fact, flax does best in somewhat moist – but not wet – climates, and it will require supplemental watering if you live somewhere with dry summers.

Pests and Diseases

There are several insects and diseases that you should keep an eye out for, and we’ll summarize several of the more common ones below. Though there are many problems that may plague this crop, you should not be too discouraged if you live in an area with the right conditions to help them to thrive. Whereas disease spreads rapidly among commercial monocrops, there’s less risk involved with starting a few homegrown plants. When grown commercially, flax is usually rotated with cereal crops like wheat to prevent disease. Even if you’re growing it on a smaller scale at home, be sure to avoid planting flax in the same area for more than three years in a row. Many of the following may affect ornamental varieties as well.

Flax Bollworm

The flax bollworm (Heliothis ononis) is a moth with larvae that feed specifically on flax flowers and seeds, leaving you with nothing to harvest. It is found throughout parts of western Canada and the northwestern US.

The larvae look like green inchworms with white stripes along their backs and sides. If you see these on your plants, remove and dispose of them. Trichomalopsis sarcophagae, a biological control agent, is also approved for use in Canada, at least by commercial growers.

Cutworms, Aphids, and Leafhoppers

Several different species of all of these types of insects might like to munch on your plants, and as you will see below, leafhoppers in particular are often responsible for the spread of various diseases. Aphids love to suck tasty sap and cutworms eat leaves, causing damage to the health of your plants. Spraying plants with a strong stream of water all over is recommended to dislodge pests, especially aphids. Some growers also recommend sticky traps to attract insects away from your crops, but when used outdoors, these can serve to sometimes trap beneficial insects as well. Insecticidal soap may also be used. Speaking of beneficial insects, predatory bugs like ladybugs and lacewings love to eat garden pests, and their presence in the garden is more than welcome. They can even be purchased for release into the garden, but they may not choose to stick around, since they’re free to roam at will. Wasps and spiders also love to eat garden pests. To prevent and get rid of cutworms, you can try making plant collars to prevent them from accessing your flax, pick them off and dispose of them, or sprinkle diatomaceous earth around the base of plants. Find more information in our guide to cutworm control.

Rust

After a rust epidemic affecting Canadian flax crops in the 1970s, rust-resistant varieties have been developed, and the spread of this disease has mostly been resolved. Caused by Melampsora lini fungus, it can survive the winter on dead flax plant matter in the ground, and survive through several generations of plants. It can cause plants to lose their leaves, with reduced seed production and lower quality fibers. You’ll notice a bright orange, powdery residue that eventually turns black on leaves, stems, and seed bolls. If you spot rust, plants should be destroyed, as well as any plant debris in the ground, and crops should be rotated in coming seasons.

Fusarium Wilt

Caused by Fusarium oxysporum, a type of fungus, fusarium wilt may kill off young seedlings, or cause wilting and yellowing of leaves in mature plants. Since it enters a plant through the roots and affects their uptake of water, you’re more likely to notice symptoms during periods of warm weather. This type of fungus remains in the soil for several years, and spores can be spread via flax seed. Infected plants and seeds should be destroyed (not thrown onto the compost pile), and you should not grow flax or other plants that may be affected in the same soil for at least three years. Resistant varieties commonly used in commercial production today have greatly reduced the spread of this disease.

Rhizoctonia

Another fungal disease, this one is caused by Rhizoctonia solani. It’s often found in the soil where potatoes or legumes have been grown, so you should avoid planting flax in these areas.

Powdery Mildew

Caused by a fungus called Oidium lini, plants with powdery mildew will lose their leaves and produce fewer seeds. You may have seen this disease before on other plants, like rosemary. It’s exactly as it sounds – a light-colored powdery mildew will form on the leaves in just a few spots at first, but this will rapidly spread to cover the entire plant, and the leaves will wither and die. Some varieties are resistant. It’s difficult to keep a plant from succumbing to this disease once it has been infected, but you can prevent it by avoiding planting in areas that are too wet, with well-draining soil.

Pasmo

Pasmo disease is caused by Septoria linicola, a fungus that loves high humidity and warm temperatures. It can cause plants to lose their leaves, ripen early, and produce lower quality seeds. You’ll notice round, brown spots on leaves and brown or black bands on the stems of plants. The fungus can survive the winter in soil, and since no resistant seeds are available, most commercial growers rely on fungicides to treat it. Early planting and crop rotation can help to prevent the spread of this disease.

Root Rot

Root rot may be caused by the spread of various types of fungus, but boggy soil is the main culprit. Flax plants do not like to have wet feet, and sitting in water will cause them to suffer, resulting in wilting, browning of leaves, and low yields. The roots of a plant are responsible for the uptake of nutrients, so their health is important. Be sure to plant in well-draining soil.

Aster Yellows

Caused by a bacterial parasite and transmitted by six-spotted leafhoppers, this disease causes stunted growth and abnormal flower development. You’ll notice yellowing that starts at the top of plants, and they will develop sterile flowers that grow small leaves in place of petals, and fail to produce seed. Leafhoppers love warm weather, and this disease is a common problem. Read more about aster yellows disease here.

Crinkle

A viral disease caused by the oat blue dwarf virus (OBVD), it is carried by the six-spotted leafhopper, Macrosteles fascifrons. Branches of the flax plant are known as “tillers,” and this disease can cause reduced tillering, meaning less branches will grow from the central stem, as well as overall stunted growth and puckered leaves. You’ll also notice reduced seed production. Anywhere that leafhoppers are common, this disease can be a problem.

Curly Top

Caused by the beet curly top virus (BCTV), it is transmitted by the beet leafhopper, Eutettix tenellus Baker. Curly top is marked by yellowing of leaves, and leaves that develop irregularly with curling leaves that often die.

Backyard Beauties: L. Perenne and Other Ornamental Perennials

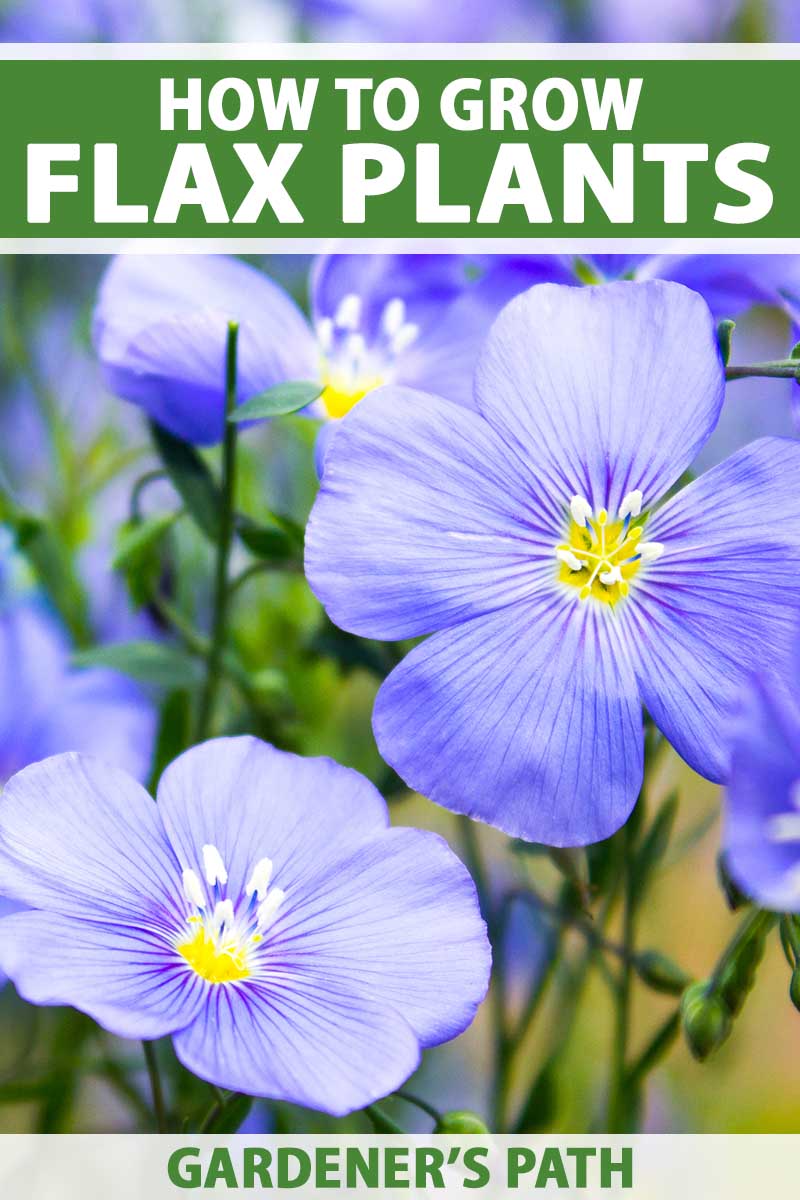

If you’re looking for an ornamental type of flax that you won’t eat or wear, but that will offer lovely flowers, consider any of the herbaceous perennial types, many of which have similar characteristics.

Planting Tips for Ornamental Varieties and Where to Buy

In general, the backyard types are drought-tolerant, deer-resistant, and appreciate full sun and well-drained soil. They’re fairly easy to care for. In terms of maintenance, you’ll want to trim ornamental types back after they flower, to encourage new growth and additional flowering.

Unless they’re looking particularly poorly, fertilizer isn’t generally needed. Just be sure to pull out any weeds that pop up around these plants. In general, the ornamental types are more shrubby than L. usitatissimum. For example, L. perenne, commonly called perennial flax, grows to a height of 1 to 2 feet, with a spread of 1 to 1½ feet.

A Multipurpose Marvel

Whether you want to weave your own cloth, produce nutritious seeds, or simply enjoy pretty flowers, flax is a good choice for many gardeners in zones 5-9. 300 Blue L. Perenne Seeds You’ll get 300 non-GMO seeds. Golden flax, L. flavum, is native to central and southern Europe. This plant grows to about 18 inches tall and is hardy to zone 5. It sprouts large clusters of pretty yellow flowers. 500 Golden L. Flavum Flower Seeds You’ll get 500 seeds that come in a resealable plastic zip-top bag with planting instructions. L. lewisii — or blue flax — is a perennial wildflower native to North America, along the west coast and across the south to the Mississippi River. It grows to about 2 feet tall and a foot in diameter, sprouting five-petaled, light blue flowers with attractive darker blue veins. Find seeds for this American beauty from Mountain Valley Seed Co., available via True Leaf Market.

L. Lewisii Seeds You can order seeds in quantities of 1 ounce, 4 ounces, or 1 pound.

The annual version is quite useful, while the perennial type offers beautiful interest to the summer landscape. Product photos via Plants with a Purpose, Seed Needs, Seedville, and Mountain Valley Seed Co. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Allison Sidhu. The staff at Gardener’s Path are not medical professionals and this article should not be construed as medical advice intended to assess, diagnose, prescribe, or promise cure. Gardener’s Path and Ask the Experts, LLC assume no liability for the use or misuse of the material presented above. Always consult with a medical professional before changing your diet or using plant-based remedies or supplements for health and wellness.