Instead, I was greeted with a honey-sweet apple-like flavor and texture. I later learned that I had just experienced my first ‘Fuyu’ persimmon, one of the most common types grown in the US. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. It seems to me that they’re gaining popularity these days, with some varieties becoming more readily available in grocery stores. But they still tend to be a rarity, and I think there are a few reasons for that. First, the astringent fruits don’t travel well at all. They need to be practically mushy before you can eat them, and as you might imagine, they can’t be stored and transported like, say, an apple. On top of that, if you’ve ever had a mouthful of tannin-laden astringent persimmon, it isn’t an experience that encourages further experimentation.

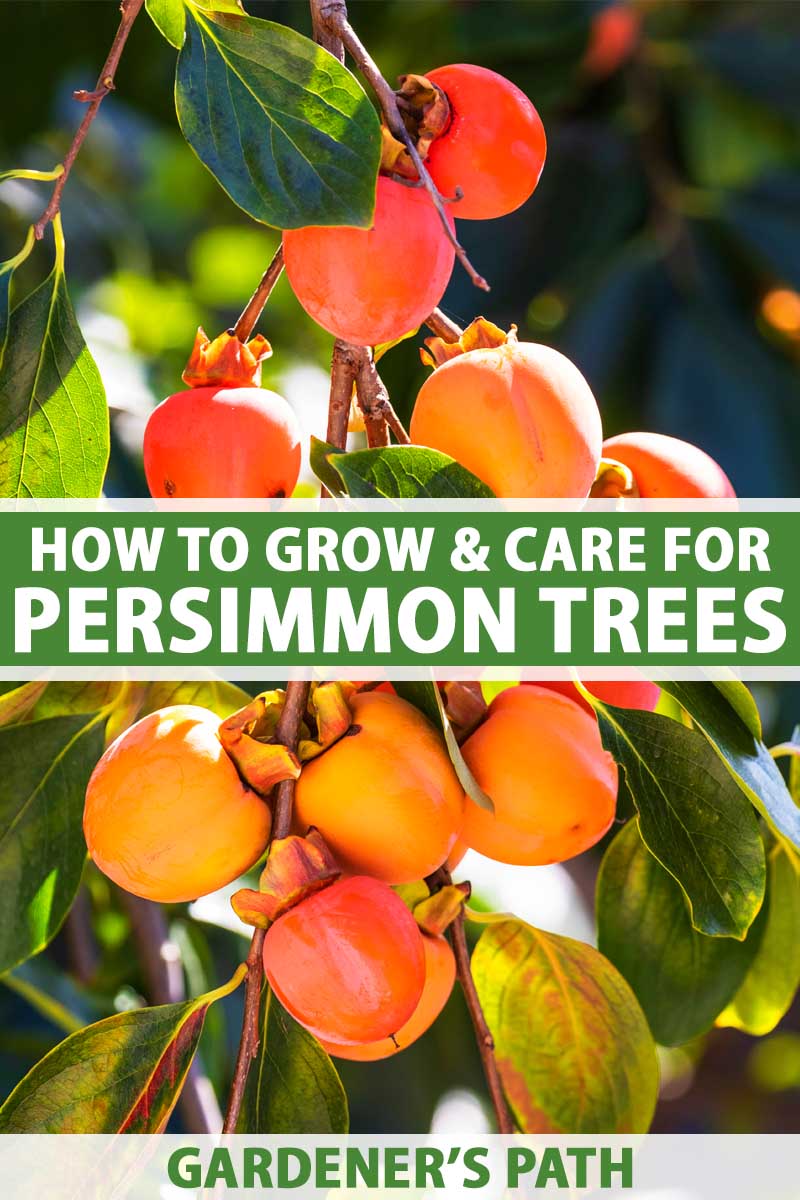

While a store-bought persimmon is still tasty, there are cultivars that you just can’t get at the market. Some are best ripened on the tree and eaten right away, and they don’t travel or store well enough to be a profitable commercial crop in the US. But a ripe persimmon is a thing to behold. They taste like nothing else, some with a bit of spice and a touch of sweet pepper combined with the essence of a plum, and others like a pear sprinkled with cinnamon and dipped in honey. While the fruits get most of the attention, these trees are so lovely that you can grow them for their ornamental value as well. But keep in mind that, similar to mulberries, you’ll need to clean up lots of fallen fruit in the winter if you choose not to harvest it at all. Fortunately, the local wildlife will help. The trees lend themselves perfectly to training into hedges, or they may be espaliered, if you want to add a plant to the garden that can do double-duty as a focal point and a provider of food. And P.S.: They’re relatively disease and pest resistant, at least as far as fruit trees go. If you live in USDA Hardiness Zones 7-10, there are dozens of cultivars available that will thrive in your area. This guide will prepare you for all the ins and outs of Asian persimmon care. Here’s what we’ll cover:

What Is a Persimmon?

Persimmon trees are members of the Ebony family (Ebenaceae). Ebony is the type of wood often used to make black piano keys, while persimmon wood specifically is sometimes used to make golf clubs.

The botanical name for the genus persimmons belong to, Diospyros, translates loosely from Greek to something like “divine fruit.” There are two closely related species that produce the familiar orange fruit: the Asian (sometimes called Japanese or Oriental) persimmon, D. kaki, which we will cover in detail here, and the American or common persimmon, D. virginiana. American and Asian persimmons are related to black sapote (D. digyna), velvet apple or mabolo (D. discolor), date plum (D. lotus), and the Texas persimmon (D. texana), all members of the same genus that produce edible fruit. Asian persimmons, unlike their American cousins, are often self-pollinating, and they can even produce parthenocarpic fruit from unfertilized flowers. That resulting fruit won’t have seeds, so it can’t reproduce. The trees can grow to be up to 60 feet tall and 25 feet wide, but some cultivars stay short or even shrub-like, topping out at 10 feet. They may produce fruit for about 30 to 50 years under ideal conditions, starting at around seven years old when they are planted from seed. The leaves are medium or dark green with smooth margins. They are lance-shaped, with a slightly lighter underside. They turn yellow, orange, or red in the fall and they often drop from the tree before the fruit is ripe.

Many cultivars are grown on grafted rootstock to help improve disease resistance and vigor. The most common rootstock comes from date plums or American persimmons. Trees are typically either male or female, though virtually all the cultivars you can purchase from a nursery are self-fruitful. That means they either have both female and male flowers, or they have perfect flowers (which are flowers that contain both male and female parts). Some trees can vary in their sexual expression from year to year. Asian persimmon trees don’t need to be pollinated to produce fruit. If the flowers are pollinated anyway, the fruit might have seeds, grow larger when mature, or have a different flavor and texture than it would otherwise. Regardless of whether they’re altered by pollination, the fruits will still taste good. They might just be slightly sweeter or less sweet. The texture is still going to be pleasant, but it might be softer or slightly firmer than what is typical otherwise. The trees flower in the spring from March through June. They need about 100 chilling hours between 32-45°F to produce a crop. The creamy white or pale yellow flowers are about 3/4 of an inch wide.

Depending on the cultivar, the fruits, which are technically berries, range from pale orange to nearly red when mature, and can be anywhere from one inch to five inches in diameter. The peels can be extremely thin or quite thick, depending on the type. The fruits may be round, tomato-shaped, heart-shaped, or egg-shaped. And there are two types of fruits in this species: astringent and non-astringent. Astringent fruit is high in tannins and doesn’t taste good until it has ripened fully. Some aren’t actually palatable until they’re overripe, and eating the underripe fruit isn’t good for humans. Non-astringent varieties, on the other hand, can be eaten even when they’re immature because they aren’t as high in tannins. In other words, they’re sweet even when they aren’t fully ripe.

Cultivars may also be classified as pollination-variant or pollination-constant. Pollination-variant trees produce fruits that develop brown flesh when pollinated, and these also have seeds. Pollination-constant fruit has the same colored flesh whether it is pollinated or not. Pollination-constant fruit that is seedless usually has flesh that is translucent and the same color as the skin. If it has seeds, there are usually darker-colored streaks in the flesh surrounding them, however, this can vary depending on the variety. It’s possible to have a seeded fruit with translucent flesh, or a seedless one that is opaque. Basically, when it comes to the flesh, as you can tell, not all persimmon cultivars look the same when you peel away the skin. Some have gelatinous flesh, while others are stringy like a pumpkin. Some are crisp, and some are soft inside. They can be completely opaque or nearly transparent. The further clarify the terminology here, the different types of trees that you are likely to come across are described as pollination-constant astringent (PCA), pollination-constant non-astringent (PCNA), pollination-variant astringent (PVA), and pollination-variant non-astringent (PVNA). Phew! What a wonderfully variable fruit!

Cultivation and History

Asian persimmons are native to central China, where evidence of their cultivation can be traced back to 450 BC. They were later taken to Korea and Japan over 1,000 years ago, where they have been cultivated ever since. In Korea, the fruit is an essential part of memorial ceremonies to this day. People in many parts of Asia use a traditional method of drying the fruits to create a sweet delicacy. In Japan, it is called hoshigaki. In Korea, the process is called gotgam, and in China, it is known as shìbǐng.

Both the fruit and the leaves have been used in traditional medicine to treat a variety of ailments. The leaves contain high levels of flavonoids, known for their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Late to the game, Americans realized how fantastic Asian persimmons could be after American naval officer M. C. Perry was first introduced to the ‘Hachiya’ persimmon in Japan in the mid-1800s and brought it to the US. Perry is often credited with “opening” trade up with the country, though that’s just a nice way of saying that he headed an expedition that forced previously isolated Japan to enter into commerce with Europe and the US.

While many Americans were already familiar with the common persimmon tree, D. virginiana, which is native to much of the South, the fruit didn’t gain wider appeal throughout other areas of the country until the non-astringent and easier to transport varieties became known. In 1914, Professor Harold Hume, Dean of the College of Agriculture at the University of Florida, began studying the plants and worked to breed new cultivars that are still being grown and sold today.

Propagation

There are many ways to start your persimmon tree, and what you choose may depend on your budget and your level of patience.

Seeds are cheap, but it will take years before you’re able to dig into your first harvest, and starting plants from seed can be a bit of a challenge. Also, seeds collected from existing trees will typically not grow true to the parent. You can always buy a live tree instead, but they aren’t cheap. Still, if you can’t wait to get cooking and enjoying fresh homegrown fruit, this is your fastest option. Dormant bare root plants are typically more affordable than saplings growing in soil, and this option is somewhere in the middle. You’ll get fruit faster than you would by starting from seed, though not as quickly as you will if you plant a good-sized live tree to begin with.

From Seed

To grow persimmons from purchased seed, first you need to put the seeds through a period of cold stratification. Start this process five months before the last frost in the spring in your area. This involves placing the seeds in a moistened paper towel and putting them in a glass jar or zip-top plastic bag. Refrigerate the seeds for three months, and don’t let the paper towel dry out. In effect, you’re trying to convince the seeds that they’ve gone through a winter period, and spring is about to come. Remove the seeds and plant each one two to three inches deep in a three-inch pot filled with seed starting mix. To make things easier at transplanting time, try using peat pots so you can simply trim out the bottom of the container before you put them in the ground. Moisten the soil using a spray bottle and keep it moist until the seeds germinate. This takes about six to eight weeks. You can speed up germination by placing the containers on a warming mat to keep the seeds around 70°F. To be on the safe side, plant about three times as many seeds as you need, since persimmons have a low germination rate. The seeds don’t need light to germinate, but once they emerge, put the containers in a sunny window where they receive direct sunlight for at least six hours a day, or use a supplemental grow light. Once the seedlings grow to be about four inches tall with at least two true leaves, and the danger of frost has passed, it’s almost time to transplant them into the ground outside. But before you put them in the ground, you’ll need to harden them off over the course of two weeks. This involves first putting the plants in indirect sunlight for an hour outdoors and then bringing them back indoors. The next day, put them outside for two hours, and three hours on the third day. Keep adding an hour until they’re outdoors for seven full hours. During the next week, put the plant in full sun for one hour and back into the shade for the rest of the day, then bring it inside again at night. Add an hour of sun each day until they are sitting in full sun for seven hours. At that point, you can plant them in their permanent spot.

From Cuttings

Fill a six-inch pot with fresh potting soil. Then, use a pencil or chopstick to make a hole in the soil and put the twig into it, inserting it about halfway.

Olivia’s Cloning Gel Cut the bottom of the twig at a 45-degree angle, and dip it in powdered rooting hormone or a cloning gel like Olivia’s, which is available at Arbico Organics. You can keep cuttings outside while they root, but be sure to keep an eye on the moisture level. If the soil dries out, the cuttings might die. Water the soil and keep it moist but not wet while the plants establish new roots. After four weeks have passed, give the twig a tug to see if it resists. If it does, it’s ready for transplanting. You might also see new leaves forming, which is another sign that they’re ready. Don’t become discouraged if your new tree isn’t ready to plant in a month. Some will take longer to get going. If you don’t see any progress after two months, toss them and start over with new cuttings next spring. If you decide to keep the cuttings indoors while they grow roots, put them in a place where they get indirect sunlight for at least eight hours a day. You’ll need to harden them off when you put them back outside, using the same process as you would for seeds. If you can’t get them into the ground in the spring before the warm weather hits, meaning anything above 80°F for the high temperature, you can plant cuttings in the ground in the fall, about a month before the first frost date in your area. In the interim, you can grow them outside in their containers.

From Seedlings and Transplanting

It’s best to purchase seedlings or young trees in the early spring. They need to go in the ground after the last frost has passed but before they start developing new growth. Dig a very deep hole for your transplant. Dig down at least twice as deep as the container the plant is sitting in. Then, mix the soil with some well-rotted compost, and some sand if you have soil with poor drainage. Then fill the hole halfway with soil and sprinkle with water to settle the earth. Add a little more soil if it becomes compacted after watering. Then, lower the new plant into the hole and fill in around it with soil. It should sit at the same soil level as it did in its container. Finally, give the tree a good drink of water. If you’re planting a grafted tree, be sure to avoid covering the little bump that formed where the plant was grafted to the rootstock. This is called the graft union, and covering it with soil can cause the scion to develop roots, bypassing the rootstock. You don’t want that!

From Bare Roots

Bare root plants can go in the ground in the early spring, while they are still dormant and before new growth has developed. It’s important to prune bare root plants before putting them in the ground. That means taking off about half of the top with a sharp pair of pruners. You should also clip away any dead roots. The purpose of pruning back the top is to prevent the roots from becoming stressed by trying to provide nutrients for more plant than they can handle. Most bare-root plants have more growing on top upon purchase or delivery than the roots are capable of feeding. It also encourages bushy growth. Keep in mind that these plants can have dark or even black roots, but that doesn’t mean they’re dead. A better way to tell is to gently bend the roots. Healthy ones will give rather than snapping. Then, plant as you would a seedling or transplant, taking care to water lightly as you put soil around the roots to make sure that you’re removing any air pockets.

Grafting

If you’re an experienced gardener with a thriving orchard, then you may already know all about grafting. Those who are new to the process will probably wonder what the heck all this means. Though this is an advanced technique that’s largely beyond the scope of this article, I’ll offer a quick overview. Basically, you’re fusing the roots and a young branch of two different trees as a way to asexually reproduce the parent plant that you take the branch from. This branch cutting is known as a scion, and in the case of other plant species, buds or young shoots may be taken from the parent plant instead. Why would you want to do this? Because it enables you to combine the positive traits of two different but related plants. In this case, Asian scions are usually grafted with American roots in order to yield the superior fruit of D. kaki grown on the more resilient roots of D. virginiana. The healthiest trees that exhibit the best qualities of fruit production, disease resistance, and appearance are selected for grafting in the same way that you might save seeds from your most productive tomato plants, or the ones that produced fruit with the best flavor. Propagating persimmons by grafting should be done in the late winter while trees are dormant, before any new branch or leaf growth emerges. You’ll need healthy rootstock with a diameter of at least 1/3 of an inch, and a scion that is about the same size or slightly smaller. Using a sharp pair of sanitized pruners, clip a piece of a branch that is about five inches long, with two to four leaf buds. Be sure to take a cutting that is alive and healthy. If it feels dry, try a different branch. Different types of cuts may be used to attach the scion to the roots. You can use a wedge graft, or a whip and tongue graft. Whip and tongue grafting involves cutting an N-shaped slice out of the root stem and a corresponding upside-down N on the scion. You then fit them together and bind them with nursery tape. A wedge graft involves creating a V shape in the rootstock stem and a corresponding wedge in the scion so that the top fits inside the bottom snugly. Again, you bind the graft point with nursery tape. From that point, you can pot up your grafted cutting and place the plant outdoors to grow. Keep the soil moist if you are having a dry late winter or early spring. If you live in a dry area year-round, mist the graft area once a day. Check on the graft to make sure the tape is in place, but that the stem isn’t growing so large that the tape is beginning to constrict it. You want to replace the tape every few weeks and check to make sure that the joint between the two plants is solid. After the plant forms new leaves and the union has formed a solid growth around it, plant the tree as you would a transplant.

How to Grow

D. kaki trees can survive in temperatures as low as 10°F, but anything colder can kill them, with just a few exceptions. I’ll mention these in the section on selected cultivars below, so keep reading!

The trees do best in areas that don’t reach temperatures above 90°F for long stretches, and they can’t tolerate drought. Too little water and the fruit will drop. If you live in a dry area, a natural mulch like straw, leaves, or grass can help the soil retain water. Plants need about an inch of water per week, so if you get that through rain, you can sit back and watch your plants grow. Otherwise, provide irrigation at the ground level. It helps to use a rain gauge to determine how much water your plants are getting so you can supplement accordingly.

They prefer full sun, but in hot regions, you may plant them in an area with some afternoon shade. Plant trees 10 to 20 feet apart from other trees or structures, depending on the expected mature size of your chosen cultivar. You’ve probably heard it before and I’ll say it again: test your soil before planting. Persimmons prefer soil with an appropriate balance of nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus. Your soil test will tell you if your soil is lacking or has too much of any of these nutrients. While Asian persimmons can handle a range of soil types, whether sandy or loamy, and rich in nutrients or not, they can’t tolerate poor drainage. When planting grafted trees, it’s important to take the origins of the rootstock into consideration. Trees grafted onto D. lotus rootstock, for example, have a higher tolerance for saturated soil than those with D. kaki or D. virginiana roots. Ideally, the soil should have a pH of between 6.5 and 7.5. Prep the soil with some well-rotted compost or sand to aid water retention or improve drainage, depending on the existing texture. The end goal is to have a loamy, healthy soil that looks like what you’d get if you bought an all-purpose soil mixture for planting. When the plants are young, you don’t need to feed them at all. As they age, you might want to supplement with fertilizer occasionally. Growing Asian persimmons in containers isn’t recommended, and they aren’t likely to fruit that way, though you may be able to keep a dwarf specimen happy in a large container in a warm climate, if you wish to grow it as an ornamental specimen. Unless a soil test shows a serious deficiency, you should skip fertilizing your trees, or stick with a 10-10-10 (NPK) product applied in the early spring. Lily Miller All-Purpose Plant Food Spread about a pound per inch of trunk diameter on the ground under the canopy of the tree.

Pruning and Maintenance

When trees are young, under five years old, you may prune them annually to develop a strong framework to support the heavy fruits. At the time of planting, aim for a “vase” configuration. This involves selecting three to five main branches toward the outside of the tree and removing all other branches.

Each year to follow, until trees reach about five years old, thin out half of the new growth while leaving the strong vase shape established by the main branches. Mature trees over five years old should be pruned in the winter when they are dormant. Remove any diseased or broken branches, then cut any crossing branches or limbs that have narrow crotches. Keep in mind that the fruit grows on new wood, so you don’t want to prune once you see new, green growth on the tree. The exception is if you see evidence of diseases or pests on your tree. In that case, trim away affected growth, no matter what time of year you notice it. In addition to annual pruning, you must thin fruit from the ‘Fuyu’ cultivar. The fruits get too large for the branches, and if there are too many on a single branch, it can break. As the fruits begin to develop, if this is the type that you are growing, trim away a fourth of the fruits from each branch. Some trees might drop some of their fruits early in the year, but this isn’t a sign that you’re doing something wrong. Most trees will try to self-regulate their load naturally. Persimmons can be susceptible to premature fruit drop. The fruits of the plant will start to develop and you’re getting all excited for those sweet treats coming down the road, but suddenly they fall to the ground. What happened? Persimmon trees can develop fruit even if the flowers didn’t get fertilized (called parthenocarpy). Most fruit flowers need to be fertilized before they will develop into fruits. That’s because fertilization combines male and female genetic material, which sends hormonal signals to the fruit to start forming. But persimmons (along with bananas, figs, pineapples, grapes, and navel oranges) can develop even if fertilization doesn’t happen. Those unfertilized fruits won’t have seeds and they are prone to dropping off the tree before they become mature. Just because a fruit wasn’t pollinated, that doesn’t guarantee it will fall, however. It can depend on the variety, climate, and conditions around the tree, as well. To prevent premature drop, make sure you have multiple compatible trees for pollination and do what you can to encourage local pollinators to visit. You should also be sure keep your plant healthy, including pruning, watering, and fertilizing as appropriate.

Growing Tips

Avoid fertilizing with too much nitrogen. Most plants need a balanced fertilizer once a year or every few years, depending on your soil. Provide around an inch of moisture each week if your trees don’t receive that much naturally. Mulch to help the soil retain moisture.

Cultivars to Select

There are hundreds of persimmon cultivars out there. We’ll touch on just a few of the most popular cultivars here. Many American-bred cultivars of D. kaki have Asian-inspired or pseudo-Asian names. Heirloom varieties often have Japanese or Chinese names. If you live in a zone that is on the cooler side of the recommended range for growing Asian persimmons, look for ‘Great Wall,’ ‘Peping,’ and ‘Sheng.’ These cultivars have been bred to be more cold hardy than most, and they can survive temperatures as low as 0°F.

Hachiya

‘Hachiya’ produces fruits with a red skin and jelly-like flesh, shaped like large acorns ‘Chocolate’ Fruits are ready to harvest in late October to early November, but make sure the fruit has gotten very ripe before digging in.

Fuyu

‘Fuyu’ means winter in Japanese, and this is one of the most well-known cultivars. The pollination-constant, non-astringent fruit (PCNA) looks similar to a tomato in shape.

‘Fuyu’ As is the case for ‘Jiro’ persimmons, there are multiple types of ‘Fuyu’ persimmons, including ‘Hana,’ ‘Giant,’ and ‘Matsumoto Wase,’ all of which were bud sports of the original ‘Fuyu.’ ‘Fuyu’ ripens late in the season and is ready to harvest from mid-November through early December. Trees in three-gallon containers are available from Brighter Blooms via Home Depot if you’d like to add this type to your orchard. They’re ready to harvest from mid-November through mid-December. This is a pollination-variant astringent type (PCA), and it is popular for drying.

Jiro

‘Jiro’ could be more accurately referred to as a group of cultivars featuring bud sport (a natural mutation) of the classic ‘Jiro’ tree. Look for ‘Maekawa Jiro’ or ‘Ichikikei Jiro,’ both of which are notable for their medium to large fruit. This tree produces firm, juicy berries that are medium in size. The fruit is pollination-constant and non-astringent (PCNA). This is a mid-season variety that’s ready to pick from mid-October through mid-November.

Managing Pests and Disease

Good news! Persimmons don’t suffer frequently from diseases or pest infestations. So why is the list that I’ve provided below so long? We have an entire guide dedicated to helping you find the right Asian persimmon cultivar(s) for your garden here. Well, that’s because there are a lot of things out there that can attack Asian persimmons, though they won’t typically attack too often or too severely. You’re more likely to have to wage war with the many critters who want to eat your fruits, so let’s start with those!

Herbivores

Persimmons are delicious, so it’s no wonder many animals enjoy them as much as we do.

Deer

When I say deer love persimmons, I mean it. They love them so much in fact that some deer attractants marketed to hunters are made from the fruit. If you aren’t careful, you’ll be sharing your harvest with hungry ungulates. The good news is that they can’t reach fruit that is high up, and they mostly dine on the stuff that falls on the ground. They only go after ripe fruit, so harvesting on time can help limit the amount of damage that they do. That said, they’ll also browse the leaves and twigs year round. Not sure how to deal with deer? We have a guide for that.

Rats

Rats will devour fruits that fall on the ground, but unlike deer, they’ll also climb trees to get to the sweet stuff. There are many ways to deal with rodents, from traps (humane and otherwise) and poison to motion-activated noise-makers and sprays. Note that using poison is illegal in many places because it can impact local wildlife, and humane traps aren’t always a good solution because many places prohibit relocating wildlife. Be sure to check local laws and regulations before you develop a plan to deal with rats in your orchard or garden.

Insects

Yes, there are many insects that may want to snack on your tree. But you aren’t likely to encounter that many of them – unless your tree is stressed. That’s why keeping your tree healthy and happy is important.

Bonide™ Rat Magic Arbico Organics carries Bonide Rat Magic, which combines several essential oils that repel all kinds of rodents. Simply sprinkle the granules around your trees.

Squirrels

Squirrels also have a sweet tooth and they love persimmons. What makes the little rodents particularly annoying is that they tend to go after the fruits about a week before they’re ripe, preventing you from allowing them to ripen fully on the tree. If you wait too long to harvest, you might go outside to pluck the ripe fruits and find them covered in little nibble marks… or missing entirely. Squirrel baffles or collars can help prevent them from scrambling up your trees, but you’ll need to make sure they aren’t able to easily circumvent this by leaping from nearby trees or structures.

Bobbex-R Animal Repellent Bobbex-R is a reliable alternative that you can spray on and around trees to deter squirrels. You can pick some up at Arbico Organics. The product that I mentioned above for rats can work to repel squirrels as well. Even though insect problems are less common than diseases, which aren’t common either, it’s vital to keep them away because they can spread various diseases that may kill your plants.

Borers

Metallic wood borers (Buprestidae spp.), also known as jewel beetles, burrow under the bark of trees. They’re actually quite lovely looking (if you can forget the damage they cause), with a metallic bronze, black, blue, and green carapace. Look for frass and gummy excretions on the trunk and underneath the bark. The tunnels can girdle a trunk, especially on a young tree or they may girdle branches. The presence of this pest goes hand-in-hand with canker issues. They lay their eggs along the scars left behind by the fungus that causes cankers. The only effective treatment is to cut into the damaged area with a sharp knife and dig out the bugs. If your tree looks unhealthy or stressed, or if the tree is still young, dig out as many of the pests as you can. Otherwise, proper care is essential. A healthy tree can often withstand an attack because the pest will move on after they pupate in the spring.

Mealybugs

Gill’s mealybug (Ferrisia gilli) is one of the most impactful pests of Asian persimmons in the western US, where the majority of the fruits sold commercially are grown. VivaTrap – Emerald Ash Borer Monitoring Trap Comstock mealybugs (Pseudococcus comstocki) are more common in the eastern US than in the western parts of the country, but they may be found in either location as well as in parts of Asia, and in their native habitat in East Asia. Longtail mealybugs (Pseudococcus longispinus) are another type commonly found across the US. Mealybugs can be gray, pinkish gray, or reddish-brown. Longtail types have long filaments extending out of their rears, and all varieties may be covered in a white waxy coating. They excrete honeydew as they suck the juice out of your trees, which attracts ants (who then help protect the mealybugs, and the cycle continues). Honeydew also attracts sooty mold. In large enough groups, they can stunt growth and reduce fruit yields, but infestations rarely get to this point. Lacewings, chalcid wasps, and ladybugs are natural predators of mealybugs, so attracting these beneficial insects to your garden can help to ward off an infestation. You should also wash your equipment between uses to remove any pests that may have hitched a ride. You can also spray plants with a strong blast of soapy water as soon as you spot these insects On young trees, you may wipe the colonies with rubbing alcohol to kill them. Use a cotton cloth or swabs soaked in rubbing alcohol. Find out more about mealybug control in our guide.

Persimmon Psyllas

Persimmon psyllas (Trioza diospyri) are a common spring pest. They generally attack persimmons as temperatures warm up and the leaves emerge. The bugs suck the juices out of the foliage, and may cause leaves to look crinkled or curled. The pests themselves are tiny, about the size of an aphid, around 0.15 of an inch long. They’re dark brown to tan, depending on their age, and have a small set of clear wings. On top of that, you’ll want to get rid of any ants, which protect and support the scale insects.

Monterey Horticultural Oil When leaves are emerging and trees are in bloom, you may spray with horticultural oil, such as this one made by Monterey that’s available from Arbico Organics to control them.

Scale

Soft scale (Parthenolecanium spp.) is an interesting pest, because it looks like a disease but is actually an insect. The little bugs are tan, brown, or gray and may have a fuzzy covering over their soft shells. They cluster together on the branches, trunks, and fruit. As they eat, they weaken the tree, which stunts growth. Examine trees for clusters of these bugs, which may look like little bumps and lumps on the stems and twigs. You may also see ants on the tree because they’re attracted to the honeydew the bugs leave in their wake.

Bonide™ Neem Oil Treat your trees with a neem oil spray once a week while the pests are present. Bonide makes a good concentrated option, which you can pick up from Arbico Organics. Find more tips on combating scale insect infestations here.

Disease

Most fruit trees are susceptible to a lot of different diseases, and the persimmon isn’t an exception. But though there are a number of diseases that can attack, healthy trees are rarely bothered by them. As I mentioned, Asian persimmons are often grafted onto American rootstock, and that’s partially because D. kaki trees are susceptible to root rot while D. virginiana and D. lotus plants are not. Before we dive in, it’s essential to keep your trees healthy. If you water at the soil level and make sure your soil is well-draining before planting, this will go a long way towards preventing many diseases. You should also prune away any dead or diseased branches as soon as you notice them. In addition, clean up any fallen fruits as soon as possible rather than letting them rot on the ground.

Armillaria Root Rot

Armillaria root rot is caused by the fungus Armillaria mellea. It starts in the roots of trees and gradually spreads up the trunk from the base, resulting in black shoestring-like strands of fungus along the exterior of the trunk. Inside, the wood and roots decay – and a stressed tree can die quickly. The fungus lives in wood debris in the soil and can spread from tree to tree through their root systems. Sadly, there is no effective treatment, so it’s important to make sure your plants are kept healthy, and provided with adequate water. Infected trees may fall over, so you’ll need to remove them entirely (roots and all) before they fall and damage your property or hurt someone. American persimmon rootstock is resistant and rarely contracts this disease.

Cankers

The fungus Botrysphaeria dothidea causes cankers and discoloration to form on the woody parts of the tree. Some branches may become girdled and the foliage may turn brown, curl inward, and fall. Avoid damaging trees while mowing or pruning, and make sure your tree is healthy, following the guidelines that I laid out at the beginning of this section. There is no treatment, so prevention is key. Prune away any damaged branches, and be prepared to remove the tree entirely in the case of a severe infection.

Root Rot

Trees planted in soil that doesn’t drain well are susceptible to rot. Root rot, caused by Phytophthora spp. water molds, causes tree growth to be stunted. The foliage may turn yellow and branch tips may die back. Meanwhile, below ground, the roots rot away. If you notice these symptoms above ground, dig down and examine some of the roots. If infected, they will look rotten and soft.

Harvesting

After planting, the trees need to grow for about three years for saplings, or seven years for plants started from seed, before they start fruiting.

RootShield Plus This biological fungicide, available at Arbico Organics, can be applied as soon as you identify the issue, or as a preventative if you’ve had this issue in the past. Follow the application instructions on the label. You don’t need to let the fruit experience a frost before harvesting, though this is a common misconception. A hard frost can actually ruin any fruits that haven’t matured yet.

Instead, harvest fruit before it is fully mature and it will continue to ripen off the plant. Wait until it reaches its mature color but is still hard in order to get it before the birds and deer do. Alternately, you may let the fruit fully ripen on the tree if there isn’t a frost coming in your near future. You’ll know it’s ready when it is soft and has reached its mature color, which may vary depending on the cultivar. Non-astringent fruit can be plucked and eaten before it is ripe and it will still be palatable. Further ripening will improve the flavor, making it sweeter. Astringent types can be harvested before they’re mature, but don’t eat them until they soften up. Use a sharp pair of clippers and snip the fruit from the stem just above the calyx. That’s the green, leaf-like bit on the top of the fruit.

If you want to hurry the ripening process off the tree, put the fruit in a bowl with apples or bananas, which give off ethylene gas. This hormone causes fruits to mature faster. The fruit is ready to eat once it feels soft. For astringent types, you want the fruit to be extremely soft to the point it almost feels mushy. Harvest time generally happens sometime from September through December. I know the fruit gets all the attention, but don’t forget the leaves of the tree. These are also edible, and you may harvest them as long as they are green and use them to make tea. It’s delicious, with an herbal flavor containing notes of caramel and nuts. Learn more about how to harvest persimmons in our guide.

Preserving and Storing

Astringent persimmons can’t be stored for very long because they need to already be so ripe once they are deemed edible. Once they reach this stage of softness, eat them within a few days.

If they aren’t ripe yet, you can place them in a bowl with another type of fruit like apples or bananas, which put off ethylene. Non-astringent types can be kept at room temperature for up to a month, or both types may be stored in the refrigerator after picking for up to six weeks (so long as they aren’t stored with other types of produce that put off ethylene, hastening the ripening process). You can also freeze the fruit for up to eight months. Wash it, dry it, and stick it in a bag, and then put it in the freezer. Fruits can be frozen whole or you can slice them, and remove the seeds and calyx.

Dehydrated persimmons are heavenly, and this is an excellent way to preserve a bumper crop. They’re like nature’s candy, if you ask me. Check out this guide on our sister site Foodal for dehydrating fruit if you want to give this option a go. Dried persimmons in Japan are known as hoshigaki. The term simply means “dried persimmon,” but it doesn’t fully capture the art that goes into making this delicacy. Essentially, you peel the astringent fruits and hang them to dry in the sun or over a warm stove. Every few days, you massage the fruits, continuing the process for a month or two until they turn brown and form a sugary crust. Bonus: If, for some reason, you have to harvest astringent persimmons early and you can’t let them ripen up all the way on the tree – perhaps because squirrels are nibbling on them, you won’t be home when they are ripe, or a freeze is in your future – dehydrating or drying them gives them a sweet flavor. To store the leaves, dry them by plucking them off the tree and putting them on a baking sheet in a cool, sheltered area with good air circulation until they feel crisp.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

The astringent aspect of this fruit comes from the tannins that they contain. Some people don’t like the astringency and think it tastes unpleasant, and some need the fruit to be fully ripe and practically jelly-like in consistency to think it tastes good.

The tannins are nature’s way of telling you not to eat too much. If you kept eating despite the mouth-puckering taste, you could develop a blockage in your digestive tract known as a bezoar. My recommendations for prep depend on how you plan to use your persimmons, but it’s always a good idea to wash and peel them before eating. Remove the calyx and any large seeds. As far as using them goes, you haven’t lived until you’ve had persimmon bread, cookies, or puddings. The deliciousness doesn’t stop there, through. Slightly underripe non-astringent varieties can be used like apples or pears, sliced and enjoyed raw in salads or on sandwiches. Try toasting a few slices on a piece of bread with some brie. They’re also tasty chopped up and roasted with white meat like pork, turkey, or chicken. Toss the fresh fruit on top of the meat, or mixed in with any veggies you have roasting with the meat, added towards the end so it doesn’t overcook. Or peel them, slice them into wedges, and bake them in an oven at 350°F for 15 minutes. Then serve them alongside sliced prosciutto, dressed with a drizzle of olive oil. You can also wrap the wedges in the meat and bake everything for 15 minutes. Instead of making peach or mango salsa, try persimmon salsa instead. Try freezing a ripe astringent type and eat it with a spoon, sort of like sorbet. Mash or slice a ripe fruit up and add it to ice cream or oatmeal.

My absolute favorite treat in the world is to bake a meringue, and top it with cream and extremely ripe persimmon. It’s also delicious on yogurt, with honey and a sprinkle of granola. Is that my stomach rumbling? Or yours? I’m not going to argue with that, because I’ve struggled with more than one fruit tree that seemed determined to die on me. But persimmons are an exception.

While I’m off begging and pleading with my pears to do better (not a recommended strategy), my persimmons are growing in the corner, just doing their thing. Most of the time, at least. And if that’s not reason enough to add a few to your yard, the fruit is exceptional. If you’ve only ever had a persimmon from the grocery store, you’ll be knocked off your feet when you take your first bite of a homegrown one. As soon as you do, I can’t wait to hear what you think. Come back and share your experiences – and your recipes! And for more information about growing fruit trees in your garden, check out these guides next:

How to Plant and Grow Asian Pear Trees How to Plant and Grow Loquat Trees How to Grow and Care for Avocado Trees

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Arbico Organics, Bob Wells Nursery, Brighter Blooms, Lily Miller, and VivaGrow Store. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Allison Sidhu and Clare Groom.