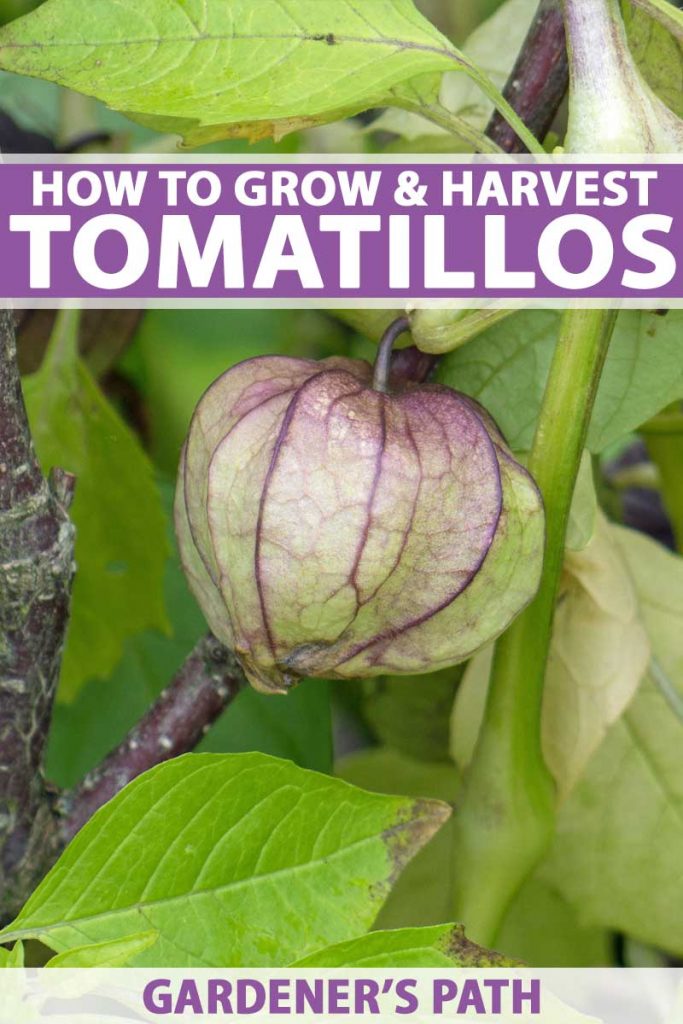

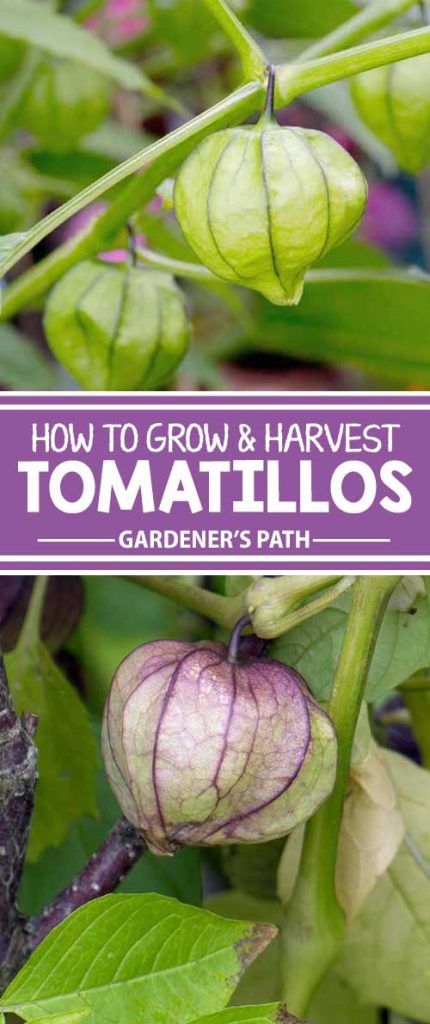

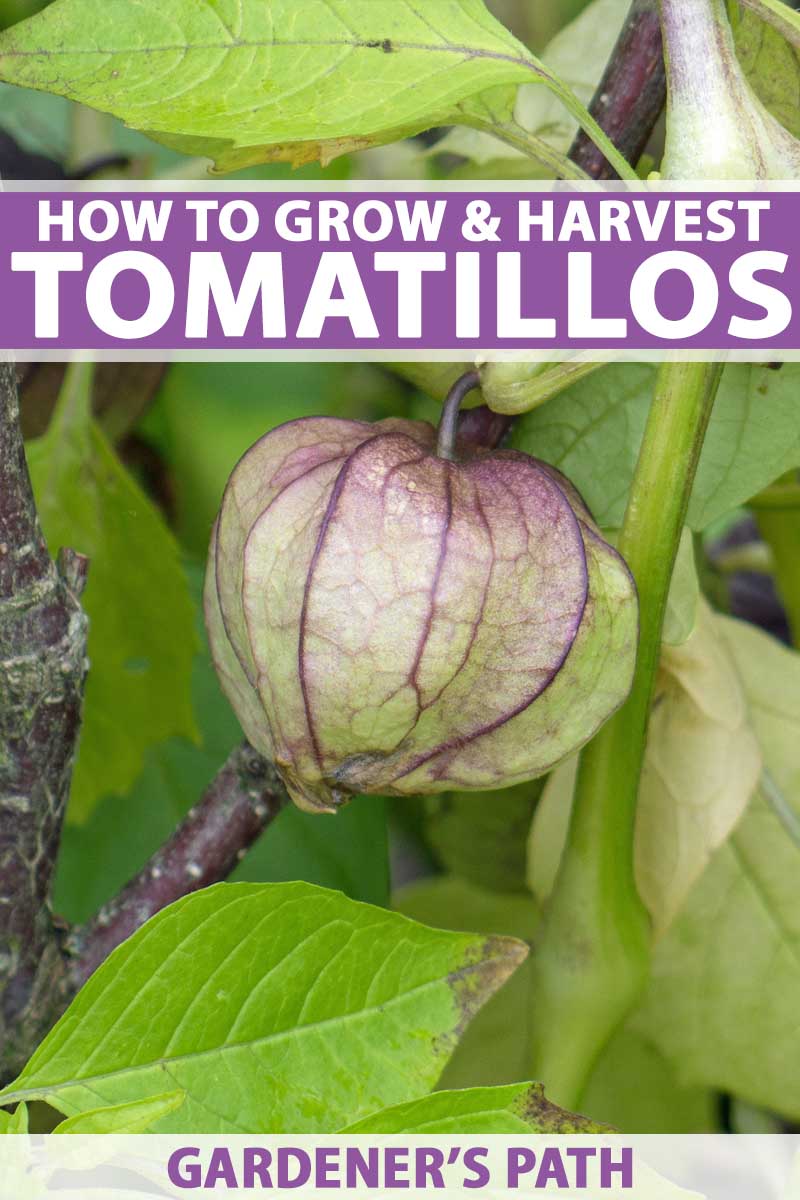

Beneath an intriguing, yet inedible, papery husk lies a fruit that, while mimicking the appearance of a green tomato, tastes nothing like a tomato. Tomatillos’ flavor instead is often described as as “citrusy”, “tart,” “sour,” and “tangy.” Some compare the fruit’s taste to that of a Granny Smith apple or a green grape. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Let’s explore the taxonomy and history of the plant, and then we’ll look at how to grow and harvest it.

The Background File

Tomatillos are part of the nightshade (Solanaceae) family, along with tomatoes and peppers. The leaves look a bit like those of eggplant, another nightshade plant. Nightshade plants are grouped together because they each produce the same particular type of flower. The fruit’s very name is a misnomer. “Tomatillo” means “little tomato” in Spanish, and while they are distantly related, the tomatillo is very definitely not a tomato. Nevertheless, nicknames linking the two tasty fruits abound, with the tomatillo also being referred to as “tomate verde” (green tomato) and “husk tomato.”

Originating in Mexico and Central America, this citrusy plant has been an important food crop for millennia, though the plant has been around for even longer. In fact, in early 2017, scientists writing for the journal “Science” reported on their discovery and analysis of a 52-million-year-old fossilized tomatillo found in the Patagonia region of Argentina. Tomatillo plants grow wild throughout their native regions, and some wild varieties in parts of the midwestern United States, where they — despite their edibility — are derisively referred to as weeds and are considered invasive. Historical records show that numerous North American native tribes used these wild fruits (Physalis longifolia) to treat headache and stomachache, according to the Native Medicinal Research Program at the University of Kansas. Prized for their unusual flavor and bright green color, these tangy fruits are now cultivated and enjoyed around the world. They can be eaten raw but most commonly are cooked. A number of purple types also exist, including Purple Coban, Tiny from Coban, and De Milpa.

And a special variety called Amarylla produces immature green fruit that are only ready to harvest once they turn yellow, contrary to the usual harvesting advice (see below). The Amarylla is known to do well for gardeners in northern zones.

Can I Grow My Own?

In North America, tomatillos are grown as an annual. As their popularity spreads, seedlings are becoming more commonly available at local garden centers, though not always at big box stores. You can also mail order seeds and propagate your own.

If you go the seed route, start them indoors six to eight weeks before the last frost is expected in your area. An important consideration when selecting transplants or starting seeds: Because tomatillos are not self-pollinating, they must be planted in groups of at least two to ensure fruiting. Most gardeners find 2-4 plants produce sufficient fruits for plenty of salsa verde. The plants’ bright yellow flowers will attract bees and other pollinators. You might also add nasturtiums or marigolds as companion plants that will attract pollinators.

Though the tomatillo is a lighter feeder than the tomato, you will nevertheless want to work about two inches of compost into the soil, maintaining a neutral pH close to 7.0. You’ll want to thoroughly aerate your soil to improve drainage, and you should grow tomatillo plants in raised beds if you have heavy clay dirt. Like their cousin the tomato, they want lots of sun, so select an appropriately bright location. And as with tomatoes, you’ll encourage strong, healthy plants if you bury 2/3 of each transplant to enable additional root growth from the stem. Space plants about three feet apart. These semi-determinate plants tend to sprawl – growing to be 3 to 4 feet tall and wide – so you might want to use a trellis, stake, or cage for support. The vines prefer well-drained soil, and can even tolerate moderate drought conditions. They do best, however, with an inch or so of water per week. They certainly won’t grow well in soaking-wet ground. Adding a 2- to 3-inch layer of organic mulch is a good idea to conserve soil moisture and suppress weeds. The vines are well-suited for container growing. Use a 5-gallon pot for each plant. Keep an eye on soil moisture, as container dirt dries out more quickly.

Don’t Get Bugged by Bugs

It’s a good idea to plant onions nearby, to help with pest control.

No particular pest is unique to the tomatillo, but their leaves are susceptible to the usual suspects, such as cucumber beetles, potato beetles and other leaf-loving bugs. Pick them off or use a natural insecticide to keep them away. You may also see aphids, which can be squirted off with a hose.

How Do I Know When They’re Ready?

The fruit is ready to pluck 75-100 days after transplanting. Pick them when they fill out their husks and the husks just begin to split. If the fruit is still small and hard and the husk is still quite loose, it is too early to harvest.

Occasionally, the husk won’t split, but turns brown and leathery; this is also a sign that the fruit is ready to be harvested. If the fruit turns pale yellow, you have waited too long. At this stage, the tasty interior becomes seedier and the flavor loses its distinctive tanginess. When you’ve identified a fruit ready for harvest, it’s best to cut it from the plant, rather than pull it, which might damage the stem. Compost damaged or overripe fruits. You can store harvested tomatillos in their husks at room temperature for up to a week or in the refrigerator either loose or in a paper bag for around three weeks. Avoid storing your harvest in plastic.

Peel away the husk before preparing for consumption. As you peel the green orbs, they will feel sticky. Just wash the fruit to remove the tacky residue. They can also can be frozen whole or sliced, or preserved by canning.

Easy to Grow, Delicious to Eat

Growing tomatillos is a fantastic way to add a new and unusual edible to your kitchen garden. If you’re comfortable growing tomatoes, you should have no trouble growing their green cousins.

Are you intrigued? Ready to introduce a new plant to your spring garden? Create a true salsa garden by installing some tomatillo plants next to your tomatoes and peppers — your family will thank you! Add a comment below to tell us your tale of tomatillos. Photo credit: Shutterstock.