While the Venus flytrap puts on an action-packed show, snapping closed dramatically when it traps insects, the sundew employs more subtle tactics. It quietly produces sap that lures smaller insects in for a taste, and ensnares them more passively, and without as much pomp. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. You’re in the right place to find answers to that question, and to learn all about how to propagate, grow, and care for this amazing plant indoors. Like something from a sci-fi novel, the sundew is a magical, botanical marvel. If you’re looking for a plant that is a true conversation piece, this may be perfect – if you don’t mind a houseplant that needs a little extra attention.

What Is a Sundew?

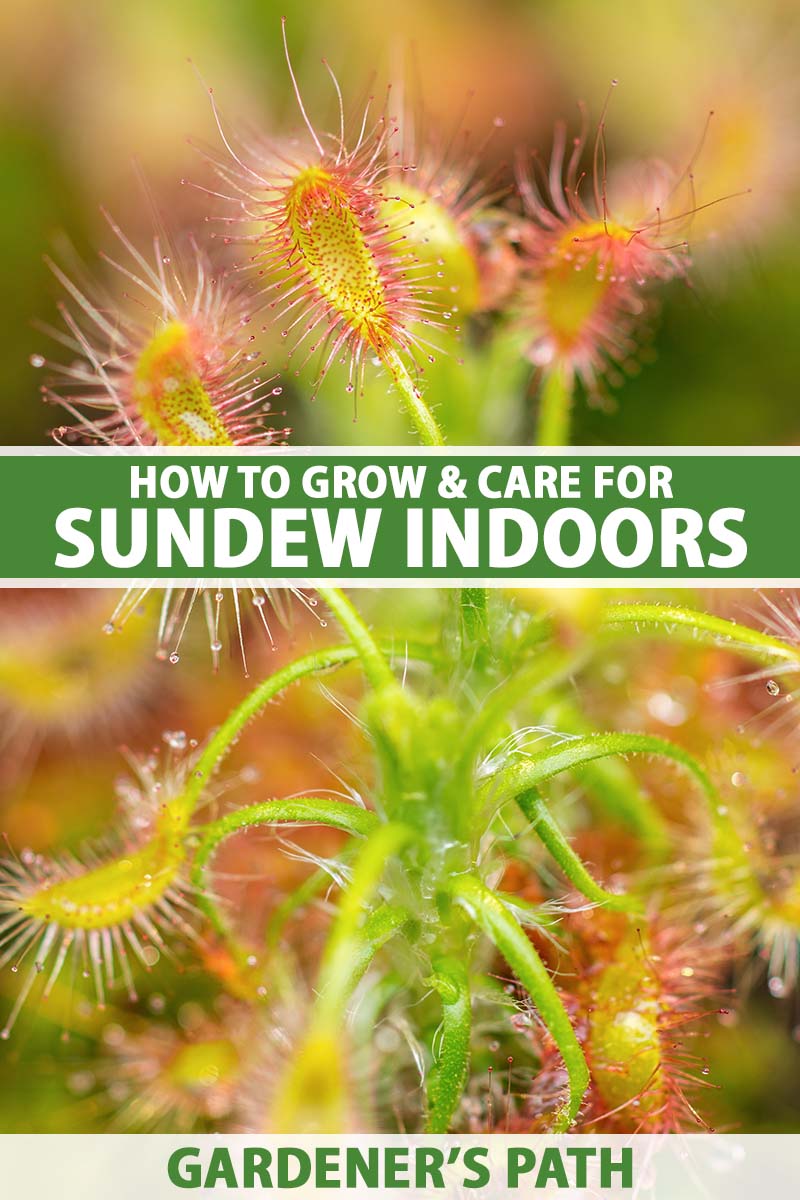

Some carnivorous plants are found only in tiny – and ever-shrinking – regions, where they’re approaching endangered status due to poaching, deforestation, over-development, and destruction of natural habitat. Most of these plants belong to the Droseraceae family, also known as the sundews. Comprised of nearly 200 species, most of which are sundews or “flypaper plants,” it also includes other species such as pitcher plants and the Venus flytrap. Unlike the Venus flytrap, which is the most commonly recognized, fewer sundew species are endangered in the wild. They have a much larger range as well, with various species found growing on almost every continent around the globe. They’re found in the wild throughout the majority of the United States, except for the southwestern portion where the climate is arid. In fact, most perennial species can grow in any wetland areas where winter temperatures drop below 50°F, as they require three to four months of cold temperatures for winter dormancy. Australian sundews, however, reverse this and go dormant in the summer because of the harsh conditions at that time of year. The Australian species D. erythrogyne is one of the largest summer-dormant species, and it’s also a climber, reaching a potential two feet in length. Another variety that’s found in Australia and regarded currently as the largest species in the world is D. gigantea, the giant sundew. This species can reach three feet in height, developing huge tubers underground that sometimes reach over nine feet deep. Leave it to the flora of the Land Down Under to go against the grain! There are also annual varieties that produce hundreds of seeds prior to dying off in the winter, such as D. capillaris, the pink sundew. This type can sometimes have a slightly longer lifespan if the blooms are cut back prior to opening, as annual types typically die after blooming. One commonality between sundew species is their growing environment, which includes bogs, marshes, and fens. All of these habitats share several characteristics, including high water tables, pine needle bedding, and the presence of a peat moss layer of earth. Soil in these areas is almost always nutrient deficient, and this has led to the evolution of plants that develop other, more creative methods of accessing nourishment rather than simply absorbing what they need through their roots. At this juncture in their evolution, sundews have adapted so well to these nutrient-starved environments that fertile soil, or even water that contains dissolved nutrients or minerals, can kill the plants. Remarkable adaptations are exhibited in the structure of the sundew. Rather than having leaves in a traditional sense, theirs are covered in trichomes, or vegetative hairs, each of which is tipped with a gland that oozes with sticky, shiny nectar. Each leaf can be covered in dozens of trichomes, or they may be present on only one side of the leaves as in species such as the Cape sundew, D. capensis. The secretions, which appear as dewdrops on the leaves – hence the name – attract foraging insects that sense the food source and attempt to land to feed from it. Rather than nipping the nectar and going along on their way, they are instead captured in the substance. Many species have leaves that are arranged in a dense rosette, which makes it practically impossible for small insects to escape once they’ve wandered into the plants’ sap. Even if they break free of trichomes on one leaf, they’ll likely get stuck in those on the neighboring leaves. In a bog environment, one of the most abundant insects is the mosquito, which makes up a significant portion of the diet of these plants. They’ve also been observed digesting gnats, aphids, ants, and even small species of bees. The larger the species of sundew, the larger the prey it can handle. Once one of these insects alights on a leaf and becomes glued to the sap, the plant then senses its struggle and responds via a process called thigmonasty. This process is triggered by special cells inside the leaves that sense movement and emit electrical currents, causing them to curl around their prey. Depending upon the species, this can take a few seconds to several hours. After the leaf envelops the insect, the plant is then triggered to secrete digestive enzymes. But if the plant is unhealthy, it may not curl its leaves around the insect. It typically takes a few days to more than a week for these enzymes to fully digest an insect, and the plant can process more than one insect at a time. However, the amount of energy that it requires to generate movement is substantial, and overfeeding may lead to leaf die-off. Because sundew prefers smaller prey insects, it makes an excellent companion to the Venus flytrap, which needs larger prey to trigger its traps to close. They thrive in the same growing conditions, so keeping them together as houseplants works well. In the wild, sundews thrive in sunny environments, but most species benefit from partial sun protection if they may be exposed to harsh sunlight and high heat, with temperatures above 80°F. If they’re overexposed to harsh sunlight, they can burn, or lose color in response. Most sundews produce long stems that can reach eight to 12 inches in height in the spring and summer. Buds form at the tips of these stems. The blossoms may be white, pink, or nearly purple, and are typically under half an inch wide. Some species are self-pollinating, and others are not. Sundews that are well-fed will generally produce more blooms, and if they’re pollinated, they’ll also produce seed. Allowing perennial plants to produce blooms and seed will not harm them as it will with some types of carnivorous plants, but annuals may die off after blooming. While the blooms may loom over the landscape on stems over a foot in height, the plants tend to be rather small for most species. Some, such as D. spatulata, the spoon-leaved sundew, only reach about one to two inches wide at maturity.

Cultivation and History

In the early 1800s, Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish “father of taxonomy,” was introduced to the Venus flytrap. His response was one of angry disbelief, as he felt no plant could be carnivorous because this would go against the will of God. Another well-known botanist, however, was not so offended. After some initial research, Charles Darwin became so enthralled with carnivorous plants, especially Drosera species, that he spent several years studying them. He conducted experiments with D. rotundifolia, feeding them various types of material and observing the results. The sundew was the first of the Drosera genus that he confirmed was in fact digesting insects as a food source, which was a breakthrough in botany. Darwin, however, was late to the game in discovering these plants, as sundews had already been used for centuries in Italian medicine. In the 12th century, a Dr. Mattheus Platearius described his use of the plant to treat patients at the School of Salerno. It’s difficult to tell when sundews were first introduced as houseplants, but during the mid- to late 1800s, carnivorous plants had gained the interest of many well-known botanists. As more species were discovered and described, laypeople were encouraged to give growing them a go, and poachers obliged. Because of the specialized growing conditions they require, hobbyists who perfected indoor habitat replication were able to produce hundreds of plants at a time, which helped to make them more widely available. Today, specialized carnivorous plant growers are found all over the world. Even though this plant appears in the wild on a global scale, each species varies to some degree – whether slightly, or greatly – from the next. Some have circular leaves, some have a more upright habit rather than in a low rosette form, and some resemble a spider’s web. Their coloration varies dramatically as well, with different species exhibiting shades of chartreuse, purple, and scarlet. There appears to be no correlation between the coloration and their ability to attract prey, as scientists once believed, but rather, it relates to how much light they are exposed to. Sundews growing in the wild in some regions face endangerment due to poaching and the destruction of their natural habitats. However, they can also produce seed prolifically, generate plantlets, and split into productive rhizomes, depending on the species, so they’re busy rebuilding their population naturally wherever they’re able to. They’re known to be exceedingly easy to propagate as houseplants as well, and make spectacularly distinctive additions to planters and terrariums. Let’s take a look at the best methods for propagating and growing your own sundew at home.

Propagation

Carnivorous sundew plants can be grown indoors using several methods, including growing them from seed, transplanting plantlets, or rooting leaf cuttings – and it’s far less difficult than you might imagine. Another hard and fast rule for growing these plants pertains to the type of water you’ll need to use when rinsing the potting medium, misting, or watering. Carnivorous Plant Soil Be sure to thoroughly rinse the coir, peat, sand, and perlite with distilled water prior to use. Only distilled water or rainwater is suitable; otherwise, you’ll introduce nutrients and minerals to the soil that will kill the plant. Keep these points in mind as you read on.

From Seed

Both perennial and annual sundews can be propagated by seed, but for annuals, it’s the most reliable method. The seeds can be so tiny that they appear to be something more akin to fine dust or powder, so you’ll want to handle them carefully to avoid losing them. Whether you’ve collected or purchased seed, if you’re not ready to use it immediately, you can store seeds in a container with a lid or a sealed zip-top bag in the refrigerator at about 35°F for several years. Because the seeds must remain wet constantly after planting, you can treat them with a light spray of neem oil to prevent mold or fungi from developing, as these can kill seedlings. Fill four-inch plastic pots with drainage holes with carnivorous potting mix, whether purchased or mixed at home. Thoroughly wet the potting medium with distilled water and press the medium into the container, pushing down so any excess fluid drains off. Carefully scatter the seeds on the soil surface and do not cover them with more than a light dusting of sand. Sand can help to hold the seeds in place until they sprout, which can aid the tiny roots in breaking ground. Mist the seeds and cover the container with a sheet of clear plastic, or place it in a clear storage tote with a lid to retain humidity. Place the container in a dish of water about one-third the depth of the pot and leave it there, making sure to refill it as water is absorbed. Use a grow light or choose a sunny location where the seeds will be exposed to eight hours of direct sunlight per day, where temperatures are constantly in the 75 to 85°F range. If you don’t have a location with consistent temperatures this warm, use a heat mat set to 75°F. Seeds should sprout within two to four weeks, and the seedlings will soon begin to resemble tiny versions of the mature plants. You can allow them to grow in a cluster, or separate them and pot them individually. Some species can grow to maturity in as little as four months.

From Cuttings

Taking leaf cuttings is one of the easiest methods of propagating sundews. Even a tiny specimen may have dozens of leaves, and these can be used to grow more plants. Cut leaves off at the base where they are attached to the central stem. Place them on a wet paper towel to keep them from drying out. Prepare a flat or small pots by filling them with dried sphagnum moss, and water it well. It should feel wet without any standing water that’s draining off. Place the leaf cuttings on the surface of the potting medium so the cut ends are pressed into the moss. Cover the container with a piece of clear plastic wrap or a humidity dome, or place the container in a clear lidded storage tote. Place the cuttings in a location that receives eight hours of direct sunlight, or under a grow light if you don’t have adequate light available. A heat mat can also be useful for keeping the growing environment at a consistent 75 to 85°F. Be sure to keep the potting medium wet, either by misting daily or bottom watering in a shallow dish filled about a third as deep as the pot. Roots will begin to develop within about one to two months.

From Plantlets

Plantlets can develop from parent plants that are sending out offshoots. After two to three months of growth, the plantlets should be mature enough to transplant. If you have a parent plant that has formed offshoots, you can typically divide them easily by removing the plant from its container and gently crumbling the soil off of the roots. A cluster can appear more mounded than an individual plant, and you may notice that some leaves start to die off as they compete with each other for space. Note that the root system can be as long as four inches, even for a tiny specimen, so take care not to damage the roots as you separate them. Pull plants apart carefully where leaves sprout from the central stem – it’s fairly simple to see the rosette pattern that some varieties form. As you divide them, place the plantlets on a wet paper towel or in a shallow dish of distilled water while they await repotting. Select individual pots that are four to six inches deep, and fill them with carnivorous potting medium. Wet it well with distilled water, and press out the excess. A finger poke should be sufficient to make an adequate hole for the root system of each plantlet. Gently place the plantlet inside. Gently compress the soil around the roots, and place the potted plantlets in a location with consistent temperatures in the 75 to 80°F range, where they will receive eight hours of direct sunlight per day. Be sure to seat the pots in a dish of water one-third the depth of the pot, or bottom water every one to two days to keep the soil consistently moist.

How to Grow

As I previously mentioned, there are more than 200 sundew species found all over the world today. As opposed to some plant genera, which can have very similar to nearly identical needs between species, the sundews may vary widely. Sundew varieties can be categorized as tropical, tuberous, rosetted, pygmy, woolly, climbing, fork-leafed, fan-leafed, or winter growing, as is the case with the South African and Australian species. Understanding that all of these species are bog or wetland plants is a good starting point, as this can help to discern some conditions that are fairly universal requirements among them – such as consistently moist soil, moderate to high humidity, and adequate feeding. In this case, rather than providing fertilizer, feeding is constituted entirely of insects. You’ll never need to add fertilizer of any kind, and it can actually damage or kill these plants. Instead, choose insects such as wingless gnats or bloodworms to feed them, for ease of handling. Both gnats and bloodworms can typically be found at pet stores, as they’re also food sources for fish and reptiles. If you’re not too keen on feeding them live insects, some growers suggest trying betta fish food pellets. These have a composition similar to what the plant would receive from an insect-based diet. Be aware that some species need to be fed daily or else they’ll rapidly decline, and ultimately die. Inadequate feeding will also slow or stop growth, making it difficult or impossible for the plant to reach its mature size. Once they reach maturity, they can be fed less often. Well-fed sundews also produce blooms frequently, which is a sign of good health. Plan to feed them at least once per month in the case of young ones, and every two to three months for mature plants. And be sure to research the variety you are growing to understand its feeding requirements. Another important requirement is direct sunlight. You’ll want to make sure your plant is receiving at least six to eight hours per day, whether that’s from a window or a grow light. Those that receive less light may have difficulty producing mucilage, or the sticky sap that exudes from the leaves. Plants that haven’t received enough light may lack color. Most species have red, orange, or purple trichomes in a sunny environment, but change to a flat, dull green without enough light. In addition to food and sunlight, moisture and humidity are extremely important. Plan to keep your potted plants in a dish of water filled to about a third the depth of the pot. Otherwise, you’ll need to bottom water at least every other day to keep the soil adequately wet. In the winter, you can reduce the amount of water that you provide in the dish to one-quarter the depth of the pot, or bottom water every two to three days, but be sure to never let the soil dry out entirely. Switch this to the summer for winter-growing varieties. Since sundews tend to produce fairly deep roots with regard to the overall size of the plant, you’ll need to pot them so they can reach deeply for water. The root system is an adaptation designed for the bog environment where the water table is high, but the ground at the surface is not typically soggy or saturated. As I have mentioned, sundews also need a special potting mix designed for carnivorous plants, consisting of coconut coir or peat moss and perlite or sand. The mix should be porous so it drains readily. They may also be grown in terrariums, but be sure to choose one that allows for the necessary rooting depth. Glass Terrarium Succulent Planter It’s a good choice because it’s tall enough to accommodate many species of sundew, including the stems that grow to hold the blooms above the plant. It also has a ventilation panel that opens at the top. Prism Glass Geometric Terrarium This is another solid choice since it’s tall enough to allow many species to bloom while offering ventilation at the top end. Or you might choose to grow them in a natural-looking planter such as this one, available from Home Depot, for a rustic touch. Natural Cement Planter Note that this planter does not have drainage holes so you’ll either need to add them, or plan to monitor the moisture level carefully. If you decide to mix your own, be sure to thoroughly rinse the peat moss, sand, and perlite with distilled water prior to planting, to be sure that they don’t contain minerals and impurities that can kill your plant. Slightly acidic soil is preferred, so sphagnum moss or pine needles can be spread on the soil surface to increase acidity and keep the soil damp. The soil pH should be between 5.0 and 6.5. You can test this at home. Most sundews prefer spring and summer temperatures between 70 and 90°F, and fall and winter temperatures between 40 and 60°F; however, some perennial varieties need colder temperatures in the winter when they go dormant. Be sure to get to know which species you have or are planning to buy, to understand its requirements.

Growing Tips

Use only potting mix formulated for carnivorous plants, or mix your own using rinsed materials. Water and rinse potting materials only with distilled water or rainwater.Never add fertilizer.Feed live insects or suitable alternative food such as fish food pellets at least once per month.

Maintenance

As I mentioned, some temperate-climate perennial sundew species will go dormant in the winter. They may either die back to the roots, or form a hibernaculum, which is a bud that the new growth will sprout from once dormancy ends. Move dormant plants to a cooler zone when you observe the seasonal die-off so they can rest and store energy for the next growth cycle. Avoid allowing dormant plants to freeze or letting the soil dry out, and keep them protected from temperatures below 32°F. If you have a cool corner in your garage or a spot in the back of your refrigerator where the plant can overwinter in temperatures between 35 and 50°F, those are good options. Leave the plant in the cooler location for two to three months, and then move it back into a warmer area starting with a few hours per day. After three to five days of exposure to warmer temperatures, you can move it back to its usual growing position. When it regrows, you’ll want to trim off any leaves that die and turn brown either from the previous season or as they come in. Avoid getting the dead material wet, as this can lead to botrytis infection, or gray mold. Smaller species don’t generally outgrow their containers unless they start off in one that is very small, but larger species will need repotting every three to four years. It’s best to repot in the spring after they have emerged from dormancy. For one to two days prior to repotting, be sure the roots are kept consistently moist to help avoid transplant shock. Prepare a container one to two inches larger than the current pot. Add enough carnivorous plant potting mix to the container to keep the plant at the level of the rim. Gently turn the plant out of the old pot, place it in the new pot, and backfill with soil around it. Press it gently into place with your hands and return the container to a dish of distilled water. After they bloom, you can allow the pollinated blossoms to go to seed and collect them. Seed pods will need to dry and turn brown to allow time for the seeds to mature fully. Use sharp, clean scissors to snip off the stem below the pods. Hold a piece of paper or a plastic bag below the stem to catch the pods, and be sure to keep them contained so you don’t lose the tiny seeds. Store seeds in a sealed plastic bag in the refrigerator if you can’t use them immediately, or plant them right away. If they’re stored at about 35°F, they can remain viable for several years.

Cultivars and Hybrids to Select

I’m not sure why anyone would go to the trouble of learning about the many different sundew varieties that already exist and still find themselves tempted to breed new cultivars and hybrids, but many horticulturists did exactly that, and the result is even more oddball bug-eating plants! Let’s take a look at just a couple of the varieties you might see on the market today.

D. capensis ‘Alba’

The Cape sundew, D. capensis, is a species found in South Africa. Typically, this species has tall, upright leaves covered in scarlet-red trichomes, but that’s not the case with ‘Alba.’ This variety has been bred for its albino traits, and where the cape sundew is red, ‘Alba’ is bright white. It’s also an easier-care cultivar that many sundew lovers enjoy.

D. capensis x spatulata

This cultivar is a hybrid cross of two species, D. capensis and D. spatulata, the spoon leaf sundew. Both parent species are very popular with carnivorous plant growers and collectors, as is this variety. The leaves of this hybrid appear elongated, combining the shape of the Cape sundew with the low-lying rosette form of the Australian spoon leaf.

Managing Pests and Disease

There are only a few issues of concern for sundew plants. But even though these pests and ailments may sometimes make an appearance, they’re less common than what you might see with many other types of houseplants. We’ll talk about the ones you are most likely to run into here.

Insects

No houseplant or garden plant list is ever complete without the inclusion of one insect pest in particular that you might also see on sundews, though both pests that we’ll discuss are common.

Aphids

Yup, you guessed it. The aphid is seemingly ever-present, and it’s always an unwelcome guest. We, the seasoned gardeners and houseplant-keepers, have fought many battles, both won and lost, against these insects. On sundews, however, it might seem like a strange situation to discover an infestation, watching a bug-eating plant being consumed by bugs. If you notice signs of damage caused by aphids – which can include curling or dying leaves, discoloration, and stunting – the best thing to do is try to remove and then smash them. But for some species, that’s almost impossible because the structure of the plant not only conceals them, but the leaves grow very closely together. Bear in mind that some sundew species can be just one to two inches wide. The best procedure for this plant is a little different than those options that commonly work to deal with infestations on other houseplants. It’s best to submerge the entire plant, pot and all, in distilled water and leave it there for about 24 hours. Take it out and let the soil drain until it’s back to a normal moisture level, and observe the effects. If you see more aphids within a few days, you can submerge the plant again. If submerging your plant fails to rid it of the infestation, you can apply a light spray of neem oil to get rid of the rest.

Fungus Gnats

The presence of mosquito-like gnats, buzzing around plants is a sign of fungus gnat infestation, and the gnats are attracted to damp soil where they’ll lay their eggs. There are many species of fungus gnats belonging to the Sciaridae and Mycetophilidae families, and all are highly attracted to bog plants such as the sundew because of the wet soil they grow best in. At one-sixteenth of an inch in length, they can be hard to spot, so by the time you notice them, they’ve probably already laid eggs in the soil. Their larvae are less than a quarter of an inch long, and even harder to spot since they spend most of their time under the surface of the soil, feeding on plant roots. Shiny, thread-like trails on the soil surface are an indication that larvae are present below. Other signs that you’ll see when the roots are damaged by the larvae include wilting and loss of leaves, caused by a secondary infection known as damping off. You can also add a product containing Bacillus thuringiensis, a type of bacteria that is ingested by the pests as they feed, killing them. This will smother the larvae and discourage adults from landing to lay eggs. Yellow Sticky Traps Sticky traps such as these, available from Arbico Organics, can attract adults. Stick them into the soil near potted plants or inside their terrarium to catch adults and keep them from laying eggs in the soil. Beneficial predatory nematodes can be added to the soil where they’ll seek out the larvae and consume them, ending their life cycle before they mature. Fungus gnats are difficult to eradicate from bog plants, so if you’re still dealing with gnats after trying all of these options, you should repot the plant in fresh soil. Be sure to thoroughly rinse the roots, and disinfect the pot as well, as eggs and larvae can hide in crevices. Read more about fungus gnat control here.

Disease

As with any wetland or water plant, moisture is crucial for survival. But unfortunately, it can also invite disease.

Botrytis

Some pathogens are commonly spread via pest infestation. Aphids and fungus gnats are often responsible for spreading Botrytis cinerea spores, which can colonize readily on sundew plants and lead to infection. Favorable conditions for colonization include humidity, warmth, and standing water. Obviously, this makes sundew plants prime targets. While consistently moist soil is essential, the plant itself should not remain wet for long periods of time. Wilting, the development of brown and black spots, and growth of fuzzy gray mold are signs that an infection has set in. Nipping an infection in the bud is best, so be sure that wetness doesn’t stay on leaves and other plant surfaces where spores can spread for more than a short period of time. You can gently tap the leaves or dab them with a dry paper towel to remove excess moisture, but avoid touching the mucilage as much as possible as you don’t want to trigger the leaves to fold. Plants that are in a terrarium should be kept under constant watch as airflow can be restricted, leading to slower drying times if they get wet. Make sure water is not dripping or settling on plants’ leaves, and opt for a terrarium that has a panel or window that can be left open to increase ventilation. If you see spots of gray, fuzzy mold developing, cut affected portions off with sharp, clean scissors and discard them in the trash. Be sure to sterilize your scissors before using them on any other plants. While fungicides could be applied, they may damage a delicate sundew, so avoid resorting to this if possible.

Root Rot

Consistently moist soil is essential to survival for any sundew, but overwatering is still a possibility. While it sounds like an oxymoron, the reality is that in nature, these plants would reach below the soil surface to access water but they would not be sitting in saturated soil. Soil that feels soupy or releases water when you press your fingers into it is too wet. Oversaturated soil can lead to wilting, loss of leaves, and die-off. A strong, mold-like odor can also emanate from the roots or soil when plants are infected. Fungal and bacterial infections caused by a host of various pathogens, such as Armillaria mellea and Phytophthora oomycetes, are more easily spread in soil that is very wet. Signs of either type of infection are the same as those caused by overwatering. Remove the plant from the soil to take a look at the roots. They should be healthy, white or brown, and firm, with no unpleasant odor or slimy texture present. Trim away any affected parts of the roots or tubers, and remove dead or dying leaves or stems with a sharp, clean pair of scissors. A sulfur-based fungicide or neem extract can be applied sparingly to the roots to combat fungal spores or bacteria. Bag the old soil and discard it in the trash. Disinfect the container or terrarium, and let it dry thoroughly before repotting. Use fresh carnivorous plant mix and distilled water to repot the plant, and avoid overwatering to reduce the likelihood of reinfection.

Best Uses

If you want to add a delightful element of living enchantment to your home, a sundew may be the perfect choice – if you don’t mind the additional caretaking requirements. Sundews can be potted in a container and placed in a sunny window or under a grow light. But there are several other ways to enjoy them inside, whether planted in a terrarium or used as part of a multi-species bog garden that combines various types of carnivorous plants such as Venus flytraps, pitcher plants, and butterwort. You might even be able to add some types of orchids. If you’d like to put your plants to use and reduce the amount of food you’ll need to offer, you might consider moving them outdoors in spring and summer, weather permitting. If temperatures in your region fall between 60 and 90°F at these times of year and you have a sunny place on your porch or patio, they can aid in insect control – they love those annoying mosquitoes and gnats! Be sure to allow time for the plants to acclimate to outdoor conditions over a period of a few days to a week instead of moving them directly into harsh sunlight or an area with a big temperature difference. Any time you move the plants indoors after they’ve been outside, be sure to give them a once-over to make sure you’re not introducing pests into your home. Be prepared for some necessary maintenance and caretaking, of course. But as you’ve learned, it’s all a matter of understanding your plants’ needs. Just like a monstera, maranta, or ficus, these plants will grow best in the hands of someone who has done their homework – and now, that’s you! Do you plan to use a container or terrarium for growing your sundew? Let us know in the comments below! And if you have any questions, we’d be happy to help. If you’re obsessed with carnivorous plants like so many others, have a read these articles next:

How to Grow a Venus Flytrap as a HouseplantHow to Grow Pitcher Plants