While it might look like the mythical King Midas had his way with the landscape, chances are that those yellow blooms were goldenrod. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. While these plants are often seen growing in spots where they planted themselves, they can also be a much welcomed, intentional member of your flower garden or landscape. We’re going to provide some tips for growing goldenrods so you can choose the species or cultivar that will fit into your landscape design plans – and one that will be at home in your growing conditions. That way, you can use these North American native species to your advantage – and theirs as well. Ready to get started? While there are plants from several different genera which go by the common name “goldenrod,” in this article we’re going to be looking at those that are currently classified in the genus Solidago, as well as one species that has since been reclassified.

What Is Goldenrod?

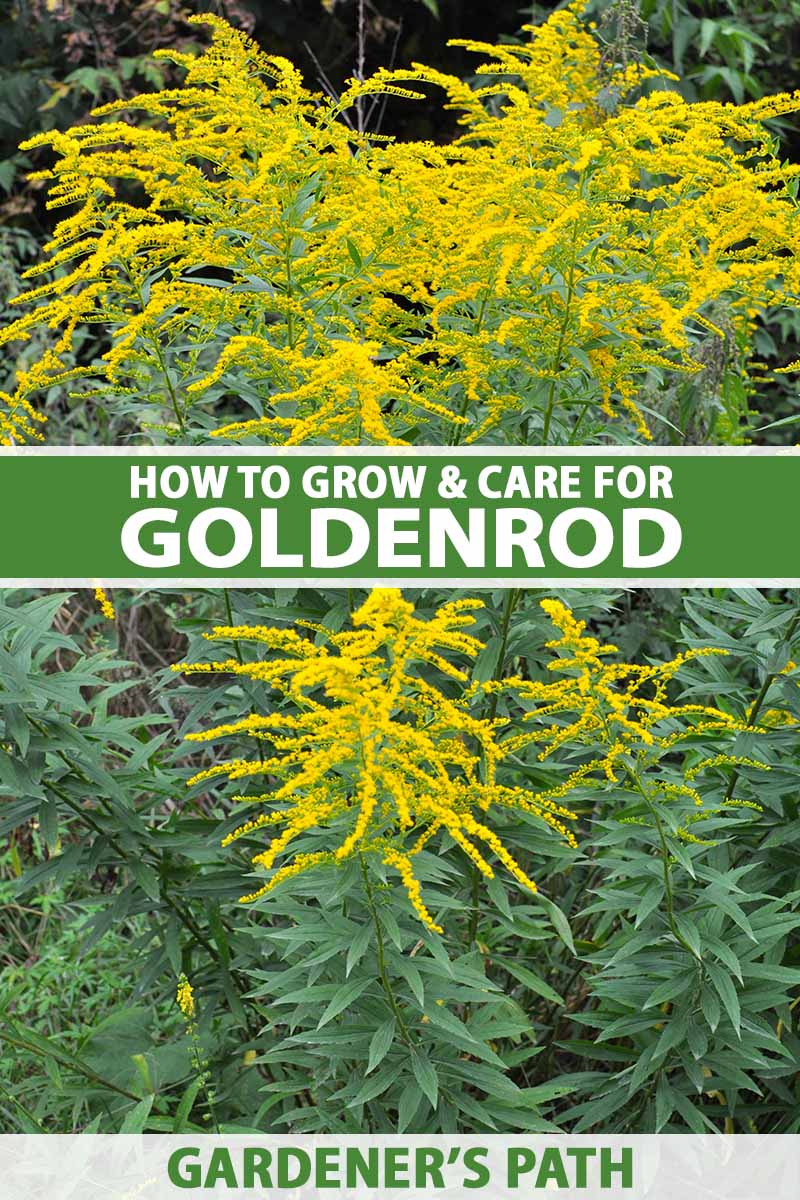

Goldenrod is the common name used for many species of wildflowers, most of which are classified under the genus Solidago, a group made up of about 100 to 120 different species. Some of these species have been reclassified and belong to different genera now, but are still widely referred to as solidagos. Goldenrods tend to produce large clusters of small flowers which are usually golden yellow, though there are some white and bicolored forms as well. The inflorescences have different shapes depending on the species or cultivar – some are held in wand-like panicles, others in flat-topped corymbs. And some clusters are held upright, while others arch delicately. Leaves are alternate, and tend to be lance-shaped or oblong, reaching four to 12 inches in length. Foliage color can vary, with some leaves that are green, some grayish green, and still others with reddish veins. Some have serrated leaf margins, while others have leaf margins that are smooth. Texture can also vary, with some goldenrods having hairy foliage, and others smooth. There is also variation in their growth habits. Some species have leaves more concentrated at the ground in the form of a basal rosette, and others have leaves evenly distributed along flower stalks. Goldenrod heights can range from six inches to eight feet, depending on the species. Underground, solidagos have rhizomes, and some species’ rhizomes can spread extensively – forming colonies up to 20 feet wide – while others are clump-forming and more restrained. If you’re thinking all this information is really nice, but your allergies won’t allow you to entertain the thought of keeping such plants in your yard, let’s take a moment to clear the record for the much-maligned goldenrods. Goldenrods aren’t actually responsible for the late summer and early fall allergies that they often get blamed for. They just happen to bloom at the same time as the real culprit – ragweed, a plant with inconspicuous flowers. Unlike ragweed’s small particles of airborne pollen, Solidago pollen is large and sticky, made for transporting by insects rather than the wind.

Cultivation and History

Solidago species are wide-ranging throughout the Northern Hemisphere and parts of the Southern Hemisphere, and can be found from North America to South America, as well as in Eurasia and northwest Africa. However, most species of this genus are native to North America – and there is a species of Solidago native to almost every county in the continental US. Goldenrods grow in a wide variety of habitats. Some are specialists growing in just one type of niche while others are generalists, able to adapt to different soil conditions, amounts of sunlight, and moisture levels. The most widespread goldenrods tend to be natives of meadows and prairies, but some types are adapted to coastal areas, bogs, moist woodlands, or dry sand dunes. Goldenrods are members of the Asteraceae or sunflower family, and are related to common garden flowers such as marigolds, cosmos, and zinnias. They’re also related to other US native wildflowers such as joe-pye weed, purple coneflower, and blazing star. Also known by the names “Aaron’s rod” and “woundwort,” goldenrods make excellent wildflowers for pollinators. However, that’s far from being their only use. To start with, their bright golden flowers can be used as a natural dye. Solidago species also have a broad history of ethnobotanical uses, being used to treat a large assortment of illnesses by many different native peoples. For instance, goldenrods were used by the Miwok, Paiute, Shoshoni, Cherokee, and Creek as cold remedies. In fact, the healing properties of goldenrods are encoded in their genus name, Solidago, which means “to make whole.”

Propagation

Goldenrods can be propagated from seed or through division. We’ll look at both methods, as well as how to transplant young starts.

From Seed

Goldenrods tend to produce huge amounts of seeds, but for some of these species, fertility is low and not all seeds are viable. So when growing from seed, sow several seeds for each specimen you hope to grow. If you end up with too many seedlings, you can always thin excess plants later. Solidago species tend to need cold, moist stratification to germinate, so direct-sow seeds in the fall or store them in moist sand in the fridge for two months prior to planting. To direct sow, first remove weeds from the planting area to allow young seedlings to get good a start without too much competition. When growing a goldenrod in its native region, you shouldn’t need any soil amendments. However, be sure to refer to growing recommendations for your particular species or cultivar before you get started. When you look up growing info for your species or cultivar, check the spacing required. Depending on your selection, goldenrods might need to be spaced as little as one foot apart or as much as four feet apart. Press the seeds into the surface of the soil, either without covering them at all, or covering only lightly – these seeds need light to germinate. Keep the soil moist but not soggy until they germinate, which can take up to three weeks. Once the young plants have a few sets of true leaves, thin them as needed, leaving one or two seedlings for each sowing area. Lacking rainfall, water regularly until plants are established. Rather than direct sowing, seeds can also be sown in pots for transplanting later, and started indoors or in a greenhouse or cold frame. For this method, sow seeds in late winter. For this project, along with seeds, you’ll need seed-starting medium, nursery pots, something to hold in humidity, and possibly a heat mat. Be sure to harden off young goldenrods before transplanting, placing them outdoors in a protected location for a short amount of time, and gradually increasing their outdoor time and exposure to direct sunlight, wind, and cold temperatures until they can withstand conditions for a full day. Deep pots with grooves along the edges called “root trainers” will encourage the goldenrod’s roots to grow down instead of tangling among themselves. And since they are hinged, these pots make it easy to remove the transplants when it’s time to relocate them to the ground. 32-Cell Deep Rootrainers with Holding Tray and Dome You can purchase packs of 32-cell Deep Rootrainers with a holding tray and humidity dome from Gardener’s Supply. Fill pots with growing medium, leaving an inch of space at the top to facilitate watering. Sow seeds on the soil surface since they require light to germinate, placing at least five seeds per cell. Water gently with a spray bottle, then cover each pot with a plastic bag, or the entire tray with a dome, in order to keep in humidity. Provide full sun or use a grow lamp and keep seeds warm, preferably at 80 to 86°F to achieve the best germination rates, using a heat mat if needed. Jump Start Heat Mat Expect seeds to germinate within one to three weeks. As the seedlings grow, keep the growing medium moist but not soggy. Once the seedlings have a few sets of true leaves, thin them to two plants per pot or cell.

From Division

Division is generally considered the easiest method of propagating solidagos – especially since many goldenrods spread so eagerly. Plan to make your divisions in late winter or early spring for best results, preferably on a cloudy day, so this operation will be easier on your plants. Strong spreaders such as S. canadensis will need to be divided every two years, while hybrids can be divided every four or five years. Prior to dividing, water the parent plant a couple of days in a row prior to the big day, so surrounding soil is moist, but not soggy. When you’re ready to divide, first prepare the area where the divisions will go – dig your holes and have them ready and waiting so your uprooted goldenrods don’t have to wait around while you dig. Once the holes are ready, use a sharp spade to separate divisions from the plant. Cut off small sections that have at least two stems attached with intact roots, and transplant these into their new holes. Keep reading for instructions on this part of the process. Fill in the hole left behind by the missing plant material with some compost. You’ll find more tips on dividing perennials in our article.

From Transplants

Before transplanting young starts or divisions, it will help to plan out your design, perhaps with the help of a gardening journal. Make sure to provide adequate spacing between specimens – usually two or three feet will do, but be sure to consult the mature size of your species or cultivar. Choose a cloudy day for this task, if possible, to make this transition easier for the transplants, and prepare the planting area first by removing weeds. When growing a native goldenrod in its natural habitat, no amendments should be needed. When planting a non-native species, check the goldenrod’s growing requirements and compare with your soil type to decide if you need to add amendments during transplanting. Read our article on understanding your garden soil to explore this topic further. Dig a hole twice as wide as the transplant and about an inch or two deeper. Remove the transplant from its nursery pot, then loosen up the goldenrod’s roots by rubbing your hand along the side of the root ball. If the specimen is quite pot bound, you can use a hori hori or the side of the plant tag to cut through the outer roots to help loosen them up. When transplanting divisions, you won’t need to loosen the plants’ roots. If there’s any loose soil in the nursery pot, mix it with the soil you removed from the hole. This will help water pass more easily between the two different soil mediums. Situate the plant in the hole. In arid climates, you can situate the plant a bit lower than the surrounding soil surface so it is growing in a small crater, which will help catch and retain water. In non-arid locations, make sure to keep the top of the root ball level with the soil surface to avoid root and crown rot. Once the goldenrod is properly situated in its hole, backfill with soil, being careful not to cover the crown of the plant – the part of the plant where the stems meet the roots. Water in the transplants, allowing the water to fill in the hole. Once the water has drained completely, water them one more time for good measure. Make sure transplants receive adequate rainwater or provide irrigation regularly until they are established.

How to Grow

There are many different species of goldenrod, and these have different soil, light, and water requirements. In order to provide your Solidago with the best care, it’s important to know which species you are working with since their growing requirements differ dramatically. For instance, S. rigida (also known as stiff goldenrod), and S. ptarmicoides can grow in full sun and dry to medium soil, while S. canadensis, S. rugosa, and S. ohioensis (commonly known as Ohio goldenrod) prefer moist conditions in full sun. S. multiradiata requires part shade and dry, alkaline conditions. Most goldenrods prefer well-draining soil, but there are a few exceptions. For best results, choose a species native to your region and plant it where it can benefit from the sun, soil, and water conditions it prefers. Likewise, some goldenrods are aggressive spreaders while others are more restrained. Depending on your gardening plans, you’ll want to choose the type whose behavior meets your landscaping requirements. You’ll find more tips for cultivating different types of solidagos in our dedicated growing guides, as well as suggested cultivars for different uses a bit later in the article. Keep reading to learn more.

Growing Tips

Choose a goldenrod which is native to your region.Select a species or cultivar that won’t spread aggressively if you have limited space.Provide your selected goldenrod with the required sun, water, and soil to meet its needs.

Pruning and Maintenance

Solidagos don’t require much maintenance, but there are a few seasonal tasks which can keep your stand of goldenrod looking its best. In winter, consider allowing dead growth to remain in place to serve as habitat and provide food for local wildlife. In mid- to late spring, prune back established specimens to two inches tall as the plant is waking up from dormancy. Also in spring, divide spreading types every two to five years, depending on the species or cultivar. During the growing season, taller types may need staking. You can accomplish this task in much the same way as you would trellis your tomatoes – check out our article on the Florida weave for instructions. Some goldenrods can spread aggressively via self-seeding. Check your species to find out if this is an issue or not, and if self-seeding is not desired, deadhead faded flower heads in autumn rather than leaving them on the plants. There’s no need to fertilize these plants, and fertilizer can feed weeds which will compete with these ornamentals.

Cultivars to Select

There are many different species of goldenrod that have different forms, uses, and native ranges. To start with, we’re going to have a look at a few cultivated varieties to wet your Solidago whistle. This compact cultivar was another top-rated selection in the Chicago Botanic Garden’s goldenrod trials, showing excellent resistance to powdery mildew. With an explosion of arching, golden flower clusters that can reach 18 inches long, ‘Fireworks’ blooms from late summer to fall. ‘Fireworks’ has dark burgundy foliage in spring, turning dark green in summer. This variety was released by the North Carolina Botanical Garden and has a shrub-like growth habit, reaching three to four feet tall and up to six feet wide. ‘Fireworks’ was the top-rated selection in the Chicago Botanic Garden’s goldenrod trials in 1993, and it was also awarded the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award for Garden Merit in 2012. But ‘Fireworks’ is not just showy – it also has excellent resistance to both powdery mildew and rust, and is hardy in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 9. This cultivar will thrive in moist to wet soil conditions in full sun or light shade. While the straight species S. rugosa has an aggressively spreading nature, ‘Fireworks’ is a slow spreader and can be used as a landscaping plant without fear of it taking over. ‘Fireworks’ Live Plant Live ‘Fireworks’ plants are available for purchase from Burpee. You can learn more about growing rough goldenrod in our guide. (coming soon!)

Golden Baby

‘Golden Baby,’ another top-rated selection in the Chicago Botanic Garden’s goldenrod trials, is an early-blooming and compact Solidago covered with golden yellow blooms. Also known as ‘Goldkind,’ plants reach 28 inches tall and 30 inches wide with an upright growth habit. ‘Golden Baby’ is a cultivar of S. canadensis and it has a long bloom time, flowering from midsummer to fall. This cultivar is hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 8, and grows best in full sun with dry to medium wet soil. It will thrive in sandy, loamy, clayey, or caliche soil types. As a clump former, this cultivar is well-behaved in gardens and landscapes, lacking the aggressively spreading nature of the straight species. ‘Golden Baby’ Seeds

Golden Fleece

‘Golden Fleece’ is a cultivar of S. sphacelate that grows like a dense ground cover. It sports small yellow flowers from late summer to fall, reaches two to three feet tall, and has heart-shaped basal leaves. ‘Golden Fleece’ is hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 8.

Lemore

Our next selection is something of an outlier among goldenrods. ‘Lemore’ was previously considered to be a naturally occurring intergeneric cross between a Solidago species and an Aster species, and was designated x Solidaster luteus. It was considered a natural hybrid of Aster ptarmicoides and Solidago missouriensis. In the meantime, A. ptarmicoides, a type of flat-topped goldenrod also known as “upland white aster,” was reclassified as a goldenrod, making ‘Lemore’ an interspecies cross, not an intergeneric one. Now the official name of our selection for scientific purposes is Solidago x luteus ‘Lemore.’ And now that we’ve dealt with this goldenrod’s identity crisis, perhaps you’d like to know what it looks like? Panicles of flowers have cream to pale yellow petals with yellow centers and look like small daisies. This clump-forming hybrid has narrow, medium-green leaves, and reaches up to three feet tall and two feet wide. ‘Lemore’ received the RHS Award for Garden Merit in 1993. Grow ‘Lemore’ in full sun. It will thrive with well-draining sandy, loamy, or chalky soil.

Managing Pests and Disease

With the resilience that most native plants show, for the most part, solidagos are fairly resistant to pest and disease problems. Serrated leaves are lance shaped on plants that reach a diminutive eight to 14 inches tall, with a 12- to 18-inch spread. This clump former requires full sun, tolerates average, sandy, and clay soils that are dry to wet, and is hardy in Zones 5 to 9. ‘Little Lemon’ Live Plants You’ll find ‘Little Lemon’ for purchase as a live plant from Nature Hills Nursery. There are many more types of goldenrods to choose from – learn more about different types of goldenrods you can choose from here.

Herbivores

Deer and rabbits may nibble on young specimens but tend to ignore mature Solidago specimens, so protect seedlings and new transplants. You’ll find tips on deer-proofing your garden and keeping rabbits out in our articles.

Insects

As for creepy-crawly critters, lace bugs (Tingidae) and spider mites might set up camp but these don’t usually constitute a worry. Gall insects sometimes take up residency in goldenrods, causing bulbous growths in stems, but local bird populations should keep damage in check. After all, part of the fun of growing native plants is seeing the communities of wildlife that have developed partnerships with them! Blister beetles (Epicauta spp.) are pollinators of goldenrod but they can sometimes be destructive, eating both the pollen and the stigmas of the flowers. However, I have a population of blister beetles that appear in my garden every year and they never do any noticeable damage. So don’t feel the need to go on the attack at the first sight of one of these little beetles. For cases when blister beetles or other pests become not just a presence but a problem in your Solidago patch, be sure to take advice from our article on integrated pest management.

Disease

When it comes to disease, rust, powdery mildew, and leaf spot can show up on these species. To prevent infection, follow recommended spacing guidelines to ensure air movement around plants. You might also consider starting with a disease-resistant species or cultivar. Other steps you can take to prevent disease include being sure to avoid overwatering and over-fertilizing.

Best Uses

When landscaping with goldenrod, it’s important to choose a species or cultivar that can properly fit the role you want it to fill. Some species, such as S. canadensis, can be aggressive, forming colonies 10 to 20 feet across. These selections will be put to good use in where their spread will be a virtue, such as in meadows or other large-scale wildflower gardens where they can naturalize. Find tips for growing a native wildflower landscape in our article. Once you have selected the right type for your needs, remember that most species are late bloomers. Taller types will be well placed at the back of a planting where their green mass of foliage can provide a backdrop for earlier bloomers. For more confined spaces, clumping species or cultivars will behave nicely in a border or cottage garden. Goldenrods can also be used in cut flower gardens, and they make excellent, brightly colored fillers for fresh flower arrangements. Other uses include planting in pollinator gardens or butterfly gardens, providing forage for migratory species with their late-season blooms. Some goldenrods are host species to butterflies and moths, such as the wavy-lined emerald moth (Synchlora aerata), so landscaping with these plants can provide much-needed habitat and food for wildlife. And while wildlife care might be one of your priorities, you wouldn’t be amiss to consider aesthetics as well. Goldenrods look lovely when combined with either purple asters or blue asters, which are also late-season bloomers. The color of goldenrods tends to match the golden centers of asters just perfectly, while the textures of the two flowers contrast, providing visual interest. And one final tip – many species of Solidago are tolerant of juglone toxin, making this perennial a great choice for using near black walnut and pecan trees. Remember to choose a species or cultivar well-suited to your climate as well as your landscaping needs, then sit back and enjoy the golden aftereffects of your green thumb. Which goldenrod species or cultivar is your favorite? Do you think any of them can rival the delightful ‘Fireworks’? And what are your plans for this wildflower in your own garden or landscaping project? Be sure to let us know in the comments section below. And before you finish your landscaping plans, you might want to check out these other wildflower growing guides next:

How to Grow and Care for CoreopsisHow to Grow and Care for Prairie OnionHow to Grow Black-Eyed Susans, a Garden Favorite