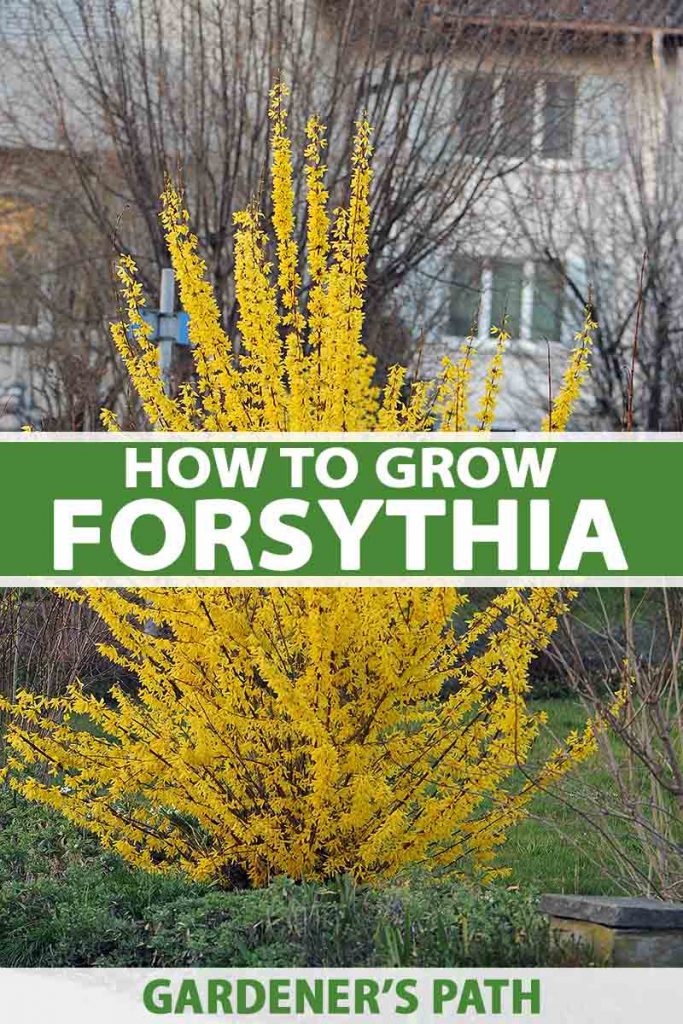

Suited to gardeners in USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 8, these plants are fast-growing and range in height from 12 inches to 10 feet tall. In this article, you’ll learn how to cultivate and maintain forsythia in your outdoor living space. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Let’s find out how this ornamental shrub made its way to the American garden.

Cultivation and History

The history of forsythia as outlined by members of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum reveals popularity among gardeners progressing through Japan, China, Europe, and Korea, before becoming a botanical attraction and finally a garden staple in the United States. Here in the Northeast where I live, it has naturalized to the point where many folks presume it is a native species. In the late 1700s, a Dutch expedition of plant collectors travelled to Japan. One was Carl Thunberg, a student of the prominent Swedish botanist and taxonomist, Carl Linnaeus. He brought back a shrub with arching branches and yellow flowers that was thought to be a lilac, and classified it as Syringa suspensa. In the 1800s, it was decided that the plant was not actually a lilac, and the Forsythia genus was created. The new species was called Forsythia suspensa, in honor of William Forsythe, a Scottish botanist who was a founding member of the Royal Horticultural Society, and Director of the Royal Garden at Kensington. Dutch cultivation continued into the mid-1800s, when Scottish botanist Robert Fortune made a trip to China for the Horticultural Society of London.

He brought back a specimen classified as F. viridissima, with upright branches and yellow flowers tinged with green, that was found to be less cold hardy than F. suspensa. In the late 1800s, a plant was discovered in a German botanical garden that appeared to be the result of an unintentional cross between the two known forsythia species. It was named Forsythia x intermedia, and would become the basis for many of today’s cultivated varieties.

At the end of the 19th century, a species was discovered growing in Albania. It had fewer flowers and less ornamental appeal than other types, and was named F. europaea. It remains the only known species not of Asian origin. In the 1920s and ‘30s, new species were identified, including the exceptionally showy F. viridissima var. koreana. By 1940, the cultivated variety F. viridissima ‘Bronxensis’ was on display in the New York Botanical Garden. Today, common border forsythia, F. x intermedia, and its many named cultivars, are the most readily available plants on the market for the home gardener. They are hardy shrubs that tolerate a variety of soils and exhibit excellent drought and salt tolerance.

Propagation

Forsythia is easy to cultivate and grows fast. Larger types may put on as much as 24 inches of new growth in one year. Brooke Beebe and Carolyn Summers from The Native Plant Center at Westchester Community College lists forsythia as a common invasive species, although the USDA does not make this designation. Forsythia is stoloniferous, which means when a branch comes in contact with the soil it can take root and start another bush.

For beginning gardeners, or those who think they don’t have a green thumb, this is an amazing plant to experiment with to build confidence. You’ll know what I mean when you read the following seven – yes seven – ways to get your own plant started:

Bare Rootstock Burlap Bagged Rootstock with Soil By Division Layering From Seed Nursery Pots Stem Cuttings

Let’s take a look at each method.

Bare Rootstock

Online nurseries often supply bare rootstock because it is lightweight and cost effective to ship through the mail. It consists of a rooted stem with all of the soil removed. When you receive it, in the fall, it needs to be watered and planted as soon as possible. To do this, set the roots in a bucket of water while you work your garden soil to a depth of about 12 inches. Amend the soil with compost, leaf mulch, or sand as needed to ensure good drainage. Settle the bare roots into the soil so that the crown – where the roots and stem meet – is about an inch above ground level. Backfill with soil and tamp it down. Water well. Tamp again to remove air pockets in the soil.

Burlap Bagged Rootstock with Soil

The roots and soil, with at least one established stem, are contained in a biodegradable burlap sack that should be planted directly into the ground. This is the quickest, easiest method, but also the most expensive. Prepare a bed of soil as described above. Place the entire biodegradable bag into the soil so that the crown, where the stem meets the roots, is about an inch above ground level. Backfill with soil and tamp it down. Water well, then tamp the soil again to remove air pockets. Burlap bagged rootstock is best planted in the fall.

By Division

Dividing plants works very well with soft, herbaceous perennials, but it’s a little more difficult with woody shrubs. The process, which is best done after blooming or in the fall, involves digging straight down through the roots of an established plant to separate it into two or more plants. It requires strength to force the shovel down, break the roots, and lift the mound of soil and plant from the ground in order to transplant it elsewhere. In addition, you may have to trim down some stiff old canes to be able to work your shovel into the plant to do the job. For more information on this process, see our guide to dividing perennials. Once you have a section divided, transplant it to the desired location. Prepare the soil as described above. Set the plant into the soil so that the crown is about an inch above ground level. Backfill with soil and tamp it down, water well, and then tamp again to remove any air pockets.

From Seed

Growing forsythia from seed is generally not recommended, as viability and germination rates are uncertain. Cultivated varieties, especially hybrids, can’t be counted on to replicate the quality or traits of a parent plant. If you do decide to sow seeds, here’s how to do it: You may start seeds indoors six to eight weeks before the last average frost date, or direct sow them after the date has passed. Sow seeds quarter of an inch deep in potting soil and put them in a warm place, out of direct sunshine. Keep them moist, but not soggy. Thin the seedlings to one per starter pot or egg carton cell, and transplant them outdoors when they have at least two sets of true leaves. Place them in soil that has been prepared as above. The soil in the starter pot should be level with the ground soil. Space the seedlings according to their mature dimensions. Plant dwarf varieties one to two feet apart, moderately-sized hedge plants four to six feet apart, and the largest varieties eight to 10 feet apart. Tamp the soil and water gently, but thoroughly.

Layering

Layering is a way to make a new plant by bending the stem of an established plant to the ground and letting it take root. This process is usually done in the spring or early summer. Choose a long branch that bends easily. Look for a fresh, young cane with new growth. Bend it to the ground. Scrape about an inch of the stem, eight to 12 inches from the tip, where it touches the soil to break its cortex, the outer layer. Make a shallow depression, about 1 inch deep, in the soil beneath the bent, scraped stem. Push the stem gently into the depression and cover with soil Weigh the soil down over the stem with a small rock or brick, and keep the soil moist, but not waterlogged. In the fall, provided new growth appears, the roots will have formed and you may detach the new plant from its mother by cutting the stem that joins them. If you left your layering a little bit late, and you see no signs of fresh growth, leave it to overwinter and detach and transplant the following spring. Dig the new plant up, going down about 10 inches, and leaving a generous amount of soil attached. Transplant it to a location of your choice, where you have prepared the soil as described above. Place it in the ground so that the soil clinging to the roots is even with the ground. Backfill and tamp the soil down. Water well, and tamp again to remove air pockets.

Nursery Pots

Garden centers often have pots ranging from quart to gallon sizes that contain one or more rooted stems in potting medium. The stems may be short or tall, depending upon their age, and whether or not they have been pruned. Work the soil as described above. Unpot the plant and set it down so that the pot soil is at ground level. Backfill with soil and tamp it down, water well, and tamp again to remove any pockets of air.

Stem Cuttings

Stems placed directly into the ground can sprout roots, especially with a little help from some powdered rooting hormone. For best results, take stem cuttings in the spring. Cut a fresh, green cane at its point of origin, just above the soil line. Cut the stem into sections of about six inches long, and strip the leaves from the bottom three inches of each section. Remember to keep the cuttings oriented the same way as they were growing. Dip the bottom cut end of each individual cutting into rooting hormone powder. Use a long, narrow hand weeding tool, like you use for digging dandelions, to make a narrow hole a little wider than a cane and about three inches deep. Place a cutting into it and tamp the soil tightly around the stem before watering. New growth is evidence of successful root formation and should appear within four to six weeks. Read our full guide to forsythia propagation here.

How to Grow

There are two good times to plant forsythia – after it blooms, and just prior to winter dormancy. Once you’ve decided on a method of propagation, you need to find a location for your new shrub.

Some dwarf selections are two feet tall and wide, while some full-size varieties top out at eight to 10 feet tall and 10 to 12 feet wide. Be sure to take mature dimensions into account when deciding on a location. Choose a site with full sun. It is possible to grow forsythia in part shade, but you may have fewer blossoms. Organically-rich soil is best, but even clay is okay, provided it drains well. To improve drainage, incorporate leaf mulch or sand to loosen it up. The ideal pH may vary from a slightly acidic 6.5 to a slightly alkaline 7.5.

If you want to know your soil’s characteristics with certainty, you may contact the local extension of a land grant university about conducting a soil test. In the absence of a soaking rain, water each week during the growing season. Too much or too little water may cause yellowing of the leaves.

Growing Tips

Forsythia is a favorite of mine. When I see the buds popping, I get excited for the gardening days ahead.

Here are three tips for success:

Use mature dimensions to guide your site selection. If you don’t know what variety you have, plant it as a stand-alone specimen and let it reveal its size over the next few years.

You’ll have the showiest flowers in a location with full sun, but if all you’ve got is part shade, you should still have enough to enjoy.

Soil composition may vary from organically-rich to clay, but good drainage is essential. Amend as needed to improve drainage and prevent standing water, which can cause root rot.

Pruning and Maintenance

As mentioned, different forsythia varieties are available in sizes ranging from 12 inches to 10 feet. Take care to allow room for mature dimensions when choosing planting sites.

That being said, you have two options with this fast-growing shrub: Let it grow naturally, unimpeded and untrimmed. Prune it to a certain height and width, to fit neatly into a desired space, like a hedge. The best time to prune is immediately after flowering. This is because flower buds begin to form soon after the blossoms drop, and by summer’s end, they are in place for next year. If you were to prune at any other time, you’d cut them off and have few to no flowers the following spring. Now that you know when to prune, let me say that even if you choose a natural style, you should still prune occasionally. Remove dead or damaged stems to improve appearance and maintain good plant health. Restore youthful vigor to older bushes by randomly cutting one-third of the old wood stems to the ground every three years or so.

Hedges are a bit trickier. Prune deeply after flowering to maintain the desired shape. Pruning periodically throughout the growing season is not an option. This is because forsythia begins to set next spring’s buds soon after flowering. Pruning too late or too often is likely to cause poor flowering next bloom time. As for cutting techniques, pruning to the ground encourages the growth of long, airy canes, and is well-suited to a rounded mound with arching branches. Conversely, cutting mid-stem above a pair of leaves results in compact, branching growth more suited to well-controlled, but naturalistic border shrubs.

You may want to trim the lower branches to prevent self-layering, as it can create a ground cover you may or may not want. As for sharply manicured hedges, take care not to let the center of the shrub die. Constantly lopping off the top and sides tends to foster tip growth, but the middle receives little if any sun, and the wood there may become hard and lifeless. Promote fresh inner growth by periodically cutting down a few hardwood stems at their point of origin, to be replaced by fresh growth. Learn more about pruning forsythia shrubs here.

Other forsythia maintenance includes the option to fertilize once just before bloom time with a well-balanced, all-purpose, slow-release fertilizer, per package instructions. You may also apply a layer of mulch in the spring and/or fall. It helps with moisture retention and inhibits the growth of weeds. Place it about six inches out from the roots to avoid rotting. It’s actually Korean Ablelialeaf, Abeliophyllum distichum, a fragrant spring flower that is also in the olive family and grows and looks very much like forsythia. Occasionally, your plants may experience a false spring and bud out prematurely. Read our guide, How to Care for Cold-Damaged Forsythia, for tips on preventing and fixing freezing damage to your shrubs.

Cultivars to Select

There are 11 different species of forsythia. There was a time in the early 20th century when the upright, green stem variety F. viridissima was the reigning queen in American gardens. Today, Forsythia x intermedia cultivars take center stage, with a host of options from which to choose. Here are a few to whet your appetite for this bright yellow harbinger of spring!

Bronxensis

Straight from the New York Botanical Garden of 1940, F. viridissima ‘Bronxensis’ is a dwarf variety that tops out at a petite two to three feet tall.

‘Bronxensis’ Great for mass planting as a ground cover, a friendly low-profile hedge, or mixed border companion, this petite shrub offers the beauty of large varieties in a manageable package. Its bright yellow blossoms appear a little later in spring than most, and its leaves are lush green in summer and bronze in autumn. Find this cultivar now from Nature Hills Nursery. Choose from one- to two-foot bare rootstock, or potted rootstock in a #3 container.

Gold Tide® Courtasol

This compact Forsythia x intermedia cultivar reaches a mature height of 24 to 30 inches, with a spread of four feet. Well suited to foundation and border plantings, its lemon-yellow blossoms bid a cheerful welcome beside walkways and accented by bulb flowers.

Gold Tide® ‘Courtasol’ Find this cultivar now from Nature Hills Nursery. Choose from a one- to two-foot length of bare root, or rootstock potted in a #3 container.

Lynwood Gold

Generous clusters of bold yellow blooms line the upright branches of this six- to eight-foot Forsythia x intermedia variety. With spreads of eight to 10 feet, it makes an imposing privacy screen or specimen planting.

‘Lynwood Gold’ The foliage provides a cool backdrop of green in the summer months, before bronzing in the fall. Find this cultivar now from Nature Hills Nursery. Bare rootstock measures two to three feet.

Magical® Gold

Upright stems laden with yellow blossoms reach a compact three to four feet tall and wide. This Forsythia x intermedia cultivar is an ideal choice for hedging and smaller space gardening, where good control is desired.

Magical® ‘Gold’ Also known as ‘Kolgold,’ a noteworthy feature of this variety is that it blooms on both old and new wood, for even more luscious blooms. Find starter plants now from Burpee. While shopping, you may come across what you believe is a white forsythia.

Managing Pests and Disease

As a non-native plant, forsythia is less prone to infestation by local insect pests and the diseases they carry. Check out our supplemental guide: 11 of the Best Forsythia Varieties for Glorious Spring Color. It is one of the rare plants that is unaffected by black walnut Juglone toxicity, deer, or Japanese beetles. Adequate drainage deters water-loving pests, such as snails and slugs, and inhibits root rot. Diligent weeding, or the application of weed-inhibiting mulch six inches from the stems, also helps keep pests away. However, even with best practices, there are a couple of issues that may arise while growing this shrub. While pests aren’t usually a problem, there are some diseases to be aware of, including:

Galls

If you notice knob-like clusters of nodules on the stems of your plants, they may be galls. It can be difficult for the home gardener to identify the exact cause. It could be stem gall caused by the Phomopsis fungus, or crown gall caused by Agrobacterium tumefaciens – or a genetic deficit. Whatever the cause, these have the potential to disfigure and weaken plants. The only solution is to cut off the affected branches. Read more about managing galls on forsythia here.

Leaf Spot

Unsightly brown or black spots on the foliage may be caused by a fungus called Anthracnose. It can thrive in plants that are very dense, as the result of a buildup of humidity. Space plants well to maintain good airflow. If you have dense plantings, prune occasionally to allow air to penetrate the center of plants. And, don’t forget the importance of good drainage. Pinch off affected leaves. Apply a fungicide to inhibit further damage.

Root Rot

This is a condition caused by microorganisms called Phytophthora that resemble fungi. They may prey on the roots and foliage of woody plants, especially when conditions are too wet. Telltale signs are saturated ground, stunted growth, wilting, and rotting roots. Avoid this condition by planting in soil with proper drainage and maintaining adequate airflow. There is no treatment and affected plants must be dug up and destroyed. Do not throw infected plant matter on the compost pile, to avoid further spread.

Twig Blight

Twig blight, another problem that may arise from too much moisture, is caused by a fungus called Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. It appears as a white coating on the outside of the stems. They may also appear black on the inside. Avoid it with proper drainage and good airflow. Remove affected branches and apply fungicide. Inhibit its spread by pruning to increase airflow, and always water at the soil level. Always remember to sanitize cutting tools after removing stems that are damaged by pests or disease.

Best Uses

Flowering plants for the early spring garden all pair well with vibrant forsythia. From hellebores and snowdrop to tulip and hyacinth, it’s the perfect backdrop to a panorama of multicolor blooms.

Use a large variety as a stand-alone specimen in a garden island of its own. Or, plant a series of bushes along fences and property perimeters, where birds and small wildlife can take refuge. Smaller types play well in mixed perennial and bulb beds and borders, where they add bold color in spring and punctuate summer plantings with their attractive, lance-like, serrated green leaves.

Create mixed shrub plantings with early rhododendron, flowering quince, and pussy willow, for a pretty place to take spring holiday photos with the family. A versatile shrub that grows fast is a gardener’s best friend, when it comes to blocking an undesirable view or creating a privacy screen for the enjoyment of outdoor space.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

Your Forsythia, Your Way

Transitional flowers like forsythia are as bold as they are beautiful. They burst open on a false-spring day only to find themselves laden with snow the next. But no matter, they cling hopefully for two weeks or more, before reluctantly yielding to a profusion of serrated green foliage. In the fall, many varieties bronze to shades of gold and burgundy, often remaining attached well into winter, with next spring’s swollen buds already visible. It’s time to introduce a bush or two of one of spring’s brightest and most cheerful heralds to your landscape. Whether you cultivate tousled mounds or manicured hedges, you can count on this vigorous plant to deliver for many years to come. Are you growing forsythia in your garden? Let us know in the comments below. If you’re looking for more flowering shrubs to grow in your garden you may enjoy reading the following:

Tips for Growing Weeping Forsythia Beautiful Blooms: Add Azaleas to the Garden Growing Delicately Blooming Lilacs Grow Mellow Yellow ‘Ogon’ Spirea, a Shrub for All Seasons

Photos by Nan Schiller © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Burpee and Nature Hills Nursery. Top uncredited image by Nan Schiller. Other uncredited photos: Shutterstock.