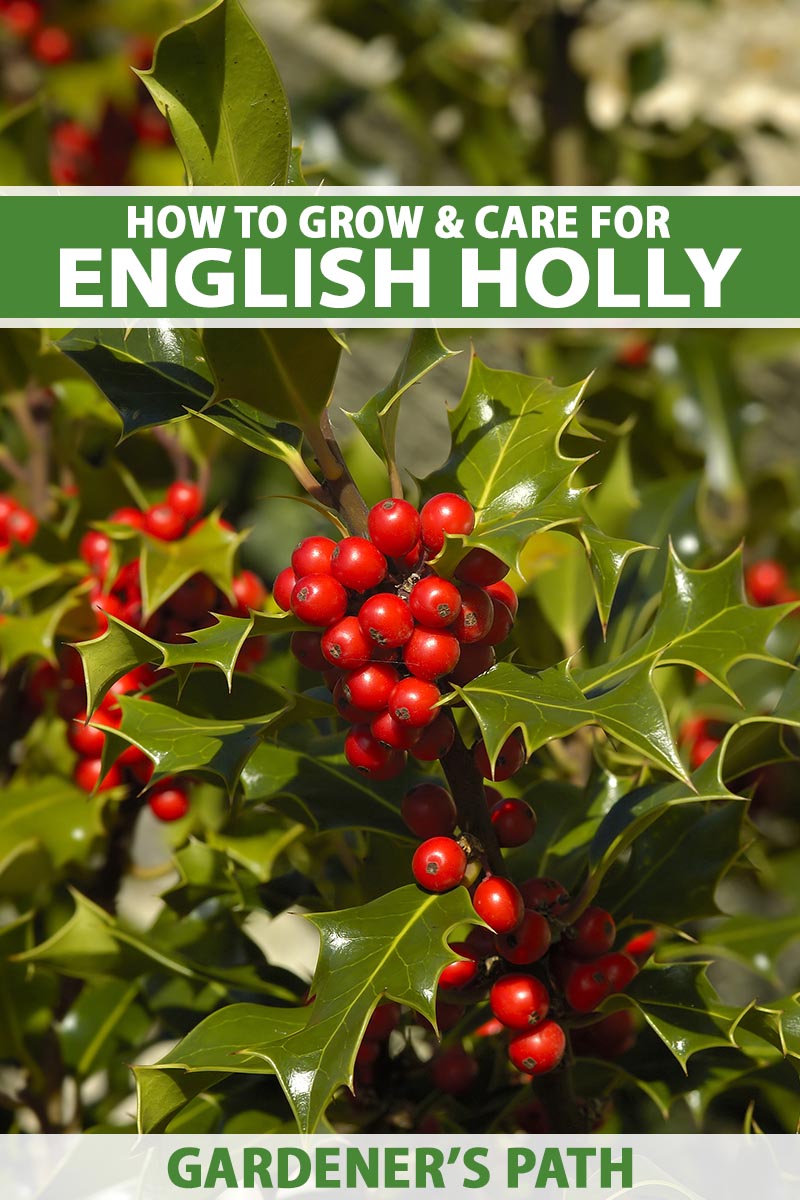

English, aka common, holly (Ilex aquifolium) is native to Europe, north Africa, and western Asia, and its sprigs are spiny, glossy green or variegated, and full of wreath-ready red berries in winter. It’s got the looks you think of when “The Holly and The Ivy” pours forth from the radio or old-school record player, and has been featured on many a Christmas card and school child’s holiday coloring page. It is the essential holiday holly in England, and some of us gardeners in the States prefer its looks to those of our own American holly, which isn’t quite as bold. Both the American and English types grow nice and tall, usually more than 30 feet, which means lots of branches for decor. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. This type of holly is not as cold-hardy as the American type, nor does it thrive in hot weather. It grows best only in USDA Hardiness Zones 7 to 9. And though I hate to sound disparaging, it can be invasive, due to its ability to be propagated when animals carry the seeds hither and yon, and also by runners when growing wild. It’s listed as invasive in some parts of California, Oregon, and Washington, for example. If you’re gardening in an area where it can grow happily, and you have the space for a hedge or a couple of specimens that could grow to 50 feet and spread 25 feet, this could be the holly for you. To get a better idea of whether it will work, and if this shrub or tree would truly please you once it’s planted, I’ll take you through some background followed by the best ways to grow and care for English holly. Here’s what to expect:

What Is English Holly?

A flowering evergreen, this is one of 560 species in the Ilex, or holly, genus. This is the only genus in the Aquifoliaceae family. Like other holly species, I. aquifolium is dioecious, meaning separate male and female plants are required in order to ensure pollination and the production of berries. Species plants and all cultivars of I. aquifolium have glossy foliage that’s usually dark green, and the leaves have thorns. Some varieties are grown primarily for their variegated foliage, while others are prized for the red berries that can remain on the plants from November through March. They also produce inconspicuous, white, scented flower clusters in spring and early summer. These attract pollinators, though only the females yield the berries that draw songbird diners, particularly in the barren winter months. As a plant that’s tolerant of air pollution, it does well along roadsides or in urban areas. But keep in mind that it may not be suitable for spaces that get a lot of foot traffic, since those spiny leaves are sharp!

Cultivation and History

Common or English holly also shares the “Christmas holly” moniker with the American variety, I. opaca. No part of the plant should be ingested, and children should be cautioned never to eat a berry of any kind that hasn’t come directly from a trusted adult.

The plant has inspired folklore and spiritual beliefs in Europe since ancient times. According to pagan winter solstice custom, the tree symbolized the waning sun and the boughs were used to decorate homes. In ancient Rome, people gave holly wreaths as Saturnalia gifts, while the Druids were said to consider it sacred due to its ability to stay green throughout the winter. The origin of placing a ring of holly on the door is Irish, and the spines on the leaves were said to snag evil spirits before they could gain entry to the home. The name “holly” may have come from Christians who adapted Saturnalia traditions to suit their own religious practice, deeming this prickly-leafed evergreen the “holy tree.” Some believers still hold that the thorns symbolize those on the crown worn by Jesus, and the red berries his blood spilled at crucifixion. In the modern day, commercial growers in the northwestern US produce this type to supply decorators and florists. For those who want to follow their example at home, growing directions are coming right up.

Propagation

I hate to strike a sour note in this holly-jolly tune, but I have to let you know that it’s not a good idea to grow I. aquifolium from seed. Not only can seeds take up to a year to germinate, the sowing approach means you won’t know whether you have male or female plants for at least a couple of years, when they start to produce flowers. And while seeds are widely available online, it’s impossible to tell whether you’re actually planting your desired variety until long after they sprout. It’s just not practical to wait many months for germination, and a couple of years after that to see if you’ve grown seedlings that will someday be able to produce berries. Happily, you can buy plants from nurseries, and there is a reliable alternative that’s inexpensive and straightforward. These evergreens are fairly simple to propagate from cuttings, following these steps:

From Cuttings

The best cuttings to work with will come from the new growth, and you can either take them from the dormant trees in winter, or from the new wood on actively growing trees in late spring or early summer. Bear in mind that you’ll need at least one male plant if you want these hollies to produce berries. Rooted cuttings are clones of the parent plants, and as such, cuttings taken from female plants will be female and those taken from male plants will be males. Before you take your cuttings, prepare the pots. You can use three- to four-inch nursery pots, provided they have drainage holes in the bottom. Just make sure to sanitize them with a 1:10 ratio of bleach to water (one part bleach to nine parts water), if they have been used before. I like to use clear, 16-ounce plastic cups to root cuttings, since they’re affordable and readily available, and it’s easy to see the forming roots inside. You’ll need to poke drainage holes in the bottom of each cup before adding the growing medium. Fill your pots three-quarters full of a 50-50, pre-moistened mix of peat moss or a suitable alternative, and perlite. Wear gloves and long sleeves to make the cuts without getting cut yourself! Those spiny leaves are sharp. Identify a branch with new growth, and cut a six- to eight-inch length of stem using clean clippers or pruners. Cover the tops with plastic wrap or a humidity dome, and place the cuttings in a room that is 60°F or warmer, in a spot with indirect sunlight. You’ll want to use a rooting hormone, like Bontone II Rooting Powder. It’s available from Arbico Organics. Bontone II Rooting Powder Dip each cut end that’s been stripped of leaves and bark in the powder, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Then jab each cutting, root powder side down, into its own prepared pot. Keep the soil moist with a spray bottle, and you should see roots forming in four to eight weeks. When the roots are a few inches long and are holding the plants steady, move each cutting to its own 12-inch container of growing medium. Keep them where they will receive at least six hours of indirect sunlight per day until it’s time to transplant.

Transplanting

Once your cuttings are established or you’ve found the variety you’d like to grow online or at a local nursery, it will be time to prepare a site where they’ll thrive – we’ll cover this in the next section. Transplanting in winter when plants are dormant is usually best, as long as the ground is diggable. Here’s how to transplant the trees or shrubs: Measure the container the start or shrub is growing in, and then dig a hole to the same depth. The width of the hole should be about three times that of the root ball, so you may need to adjust a bit once you’ve taken the plant out of its container. Break up any lumps or remove any rocks from the hole and the soil that you’ve removed. Native soil should be used to fill the hole back up after the plant is seated in its new home, but you can amend this with sand or compost to improve drainage and fertility. Separate the plant from the sides of the container using a trowel, garden pick, or spade. Then ease the plant out, being careful not to break the roots by tugging too hard. If the plant is stuck firmly inside the pot, use scissors to cut the container away, being careful not to sever any roots in the process. Once the plant’s out of the container, use your fingers to gently loosen the feeder roots so they point down instead of tangling. You may knock quite a bit of the potting soil loose when you do this, and that’s okay. Set the root ball inside the waiting hole, positioning the top of the root ball about an inch above the soil line. You may need to take the plant back out and fill in the hole a bit more with some of the dirt you removed so the root ball will sit high enough. Backfill to cover the roots and fill the hole around the plant. Water thoroughly, and get ready to give your transplants a bit of extra TLC in the following weeks. Care directions are coming up next.

How to Grow

An important growing tip for these hollies is to always plant one male per every eight females if you’d like the plants to produce berries. And plant females within 50 feet or so of the male for best results. Bees will often travel long distances to pollinate flowers. Though many gardeners delight in the sight of vibrant red berries each winter when they only have females planted on their own property, there’s no easy way to tell whether this will be the case for you in advance – unless you’re certain about the presence of other male hollies growing nearby. Plant varieties of I. aquifolium where they’ll get six hours of full sun per day, or choose a location in part shade. They’ll tolerate even more shade but they won’t grow as quickly, or produce as many flowers or berries, with less sun exposure. They can’t tolerate too much heat or direct sunlight, and will benefit from afternoon shade in warmer climates. These evergreens also require protection from wintry gusts, particularly when they are young. Choose a protected area, or build a wind barrier for the first couple of winters after transplanting, by setting stakes in the ground a few inches away around the perimeter of your transplants, and wrapping them with burlap. Don’t allow the material to touch the plants, as this can cause damage. Remove it after the bouts of cold, gusty winds have ceased in the spring. Also be sure to choose a spot with well-draining soil. These evergreens can thrive in average soil as long as it’s somewhat acidic, preferably with a pH between 3.5 and 6.8. In the beginning, these evergreens need more frequent watering in the absence of rain. It’s best to water them deeply every day for a week after you’ve transplanted if the weather is clear, and then switch to twice a week until the plants are well established. Hoffman Blue Magic Aluminum Sulfate Be sure to provide ample spacing – plant at least five feet apart to create a hedge, and 15 to 25 feet apart for specimen trees. If you plan to prune your holly to enjoy it as a shrub of moderate size, it will need a bit less space, about 10 feet between it and the nearest neighbor as long as you prune for airflow as needed. After that, they’ll still need weekly watering when the weather is hot or dry, about two inches total. Check precipitation levels with a rain gauge. You’ll know they need water when the top inch of the soil is dry to the touch, or when a moisture meter indicates the plant is thirsty! To help retain moisture, apply a one- to two-inch layer of mulch, leaving a couple of inches between the crown and the mulch to discourage rotting or waterborne diseases.

Growing Tips

Plant at least one male within 50 feet of females to ensure berry production.Provide small transplants with protection from winter winds, or choose a protected area for planting.Plant in well-draining, acidic soil.Provide sufficient water in the absence of rain, until shrubs or trees become established.

Pruning and Maintenance

Once taller than 10 feet, pruning this type of holly becomes fairly difficult, and must involve safety measures in addition to loppers, a ladder, and another person to spot. Never prune a tall tree alone, in case you lose your balance! In general, unless you’re going for a specific shape, you won’t need to prune the specimens you choose to grow as trees. But the hedges and varieties you’re trying to train as smaller 10- to 15-foot shrubs are another matter entirely. Make sure to prune annually, in late winter, just before the plant begins growing again after its dormant period. Use sharpened loppers, slip on some thick gardening gloves, and wear long sleeves and pants so you won’t be scratched by the spines on the leaves. Start by lopping off any dead branches, then move to cutting the unruly portions of branches growing sideways or towards the trunk, instead of growing in that shapely pyramid these hollies are known for. Also pare off any branch portions that have become tangled. Finally, move to shaping the rest of the shrub as needed. Mature plants can tolerate hard pruning. Prune just above new leaf buds so the holly will continue to flourish in subsequent weeks, when spring has sprung.

Cultivars and Hybrids to Select

When you’re seeking an I. aquifolium to grow, there are two main types that are extra appealing. Espoma Holly Tone This will keep the soil at the proper pH, and encourage healthy growth. The first are the ones that produce berries in addition to the leathery, glossy leaves, while others are celebrated mainly for their variegated foliage. If you’re a fan of the foliage and you’re okay with potentially skipping the show of berries, there’s no reason to worry about planting both male and female specimens. Two of the cultivars I recommend here are English holly hybrids that have been bred with other species to overcome drawbacks of growing the standard variety, with better cold resistance or a shorter stature. If you’re in it for the berries, the best pollinator will always be a male of the same species as the female. But sometimes, a male of a different species can provide suitable pollen. For example, a female English holly may be pollinated by an accessible male American holly, if you’re already growing one of those. You’ll also come across “self-pollinating” versions for sale. Though these plants are dioecious and truly self-pollinating cultivars do not exist, this term is used here to indicate that the grower has kindly placed both male and female plants in the same pot. There are a few cultivars of other holly species that are genuinely parthenocarpic, meaning they will produce fruit without the need for pollination, but none of them are of the English holly variety. Here are three popular options to consider:

Managing Pests and Disease

It may not be able to hang in severe cold or prolonged high heat, but I. aquifolium doesn’t fall prey to many diseases or insects. Many choose this cultivar for the beauty of its dark-green leaves that have off-white edges. This variety grows 15 feet or taller, and spreads eight to 12 feet.

Dragon Lady

A hardy hybrid, I. x aquipernyi ‘Dragon Lady’ is a cross between I. aquifolium and I. pernyi, and this narrow variety grows 20 feet tall and spreads six feet. A female plant, ‘Dragon Lady’ has abundant bright red berries and tough, sharp leaves recommended for property borders and defensive landscaping. This cultivar requires no pruning to keep its formal symmetrical shape. ‘Dragon Lady’ More cold hardy than the species plant, this holly is suited to Zones 5 to 8. ‘Dragon Lady’ is available in one-gallon containers from Home Depot.

Royal Family Holly Combo

This is not one, but two different hybrids that have I. aquifolium as a parent plant. The Royal Family combines a female ‘Blue Princess’ with a suitable male pollinator, ‘Blue Prince.’ Royal Family Combo Unlike traditional English holly, these two can grow in much colder climates down to Zone 4. They’re also a bit shorter and thinner, reaching 10 to 15 feet tall and eight to 10 feet wide. The Royal Family combo is available from Nature Hills Nursery in #1 or #3 containers. There are just a few serious conditions to watch out for, and a couple of bugs that may make an appearance.

Pests

According to plant pathologists at the North Carolina State Extension, a few insects may infest English holly, but the plants usually don’t suffer ill effects even after prolonged infestations. So while you don’t need to anticipate plagues, you should still be on the lookout for a few bugs. Here are the main ones:

Holly Leaf Miners

The larvae of this small fly, Phytomyza ilicicola, create blotches on the leaves when they feed. The spots are unattractive, though they won’t hurt your plant overall. You can spot the damage by looking for small raised bumps on the leaves. The first line of treatment is just plucking the affected leaves from the plant and tossing them in the trash. You may need to graduate to a spray if that doesn’t take care of the problem. Learn more methods of prevention and control in our leaf miner guide.

Scale

White blobs of Japanese wax scale (Ceroplastes ceriferus) may crop up on the wood, and cottony masses of tea scale (Fiorinia theae) may appear on the lower leaf surfaces of I. aquifolium. It’s not a big deal to remove just a few with a damp cloth or cotton balls dipped in rubbing alcohol, but in the case of more extensive infestations, see our guide to controlling scale for additional tips.

Spider Mites

The Southern red mite, Oligonychus ilicis, is quite fond of feeding on holly leaves. You probably won’t be able to spot this tiny insect. Instead, look for a telltale sign of its presence – miniature webs on the undersides of the foliage. Get rid of any leaves the mites have damaged, and then double down by spraying with neem oil once a week or so, until all vestiges of the spider mites have disappeared. If the problem persists, consult our guide on spider mite detection and treatment for more solutions.

Disease

Be on the lookout for these three I. aquifolium diseases:

Black Root Rot

The fungus Thielaviopsis basicola causes this malady. It will spread quickly when the wind disperses its spores. One of the main causes of this disease is too much moisture in the soil. Once it starts, it turns the plant’s roots brown, starting at the tips. It will cause the infected holly to languish over time, and eventually die off completely. If your plant sustains black root rot, the best solution is just to remove it and replace it with a resistant species such as Chinese (Ilex cornuta), Yaupon (I. vomitoria), or American holly (I. opaca). The Japanese species (I. crenata) is not a suitable substitute, as it is very susceptible to black root rot. Check out our guide to learn more about root rot in trees and shrubs.

Powdery Mildew

Blech! When you spot a characteristic floury sprinkling on the foliage, Golovinomyces orontiiis is making itself known. You can usually just remove the damaged leaves and then spray the rest of the foliage with copper fungicide to take care of the problem. For more homemade and organic powdery mildew solutions, consult our guide.

Tar Spot

Tar spot, also known as leaf spot, is an accurate description for this holly disease. It’s caused by a fungus called Coniothyrium ilicinum that creates tiny yellow-brown spots on the leaves. The evidence will show up in winter or early spring, progress to a red-brown by summer, and become sooty black by autumn. This malady doesn’t threaten your plant’s life, but it is pretty ugly. To discourage it from spreading, clip any diseased leaves. Then spray the remaining foliage with copper fungicide, following the manufacturer’s directions.

Best Uses

Left to their own devices, these hollies tower over the landscape. They are classified as “slow growing,” at just a few feet a year, but will eventually reach mature heights of 30 to 50 feet. Full-size I. aquifolium plants require plenty of space, so they are best grown as specimen trees, or part of a hedge of hollies planted side by side. They can spread up to 25 feet and you’ll need at least two, a male and a female, if you want the evergreens to produce berries. This species is also a songbird magnet. Cardinals may nest in the dense branches, too, if you plant them near a natural source of water or provide one. Make sure to grow them somewhere near a window if possible too, so you can enjoy the sight if songbirds start snacking there. You can also prune and train (or should I say restrain?) this variety to grow as a 10- to 15-foot shrub to plant in a border or closer to the house. Berry-producing females add color to an otherwise bleak landscape with fruit that lasts from autumn well into winter. Sprigs and boughs make a festive addition to wreaths, swags, and winter floral arrangements. Protect your fingers and arms from the prickers by donning a pair of heavy gloves before cutting the foliage. And place the cut branches in a simple arrangement in a vase or pitcher, instead of using them in an arrangement that involves lots of manipulation. Those spines can hurt, and the risk of incurring a jab increases with every sprig you cut, touch, or manipulate. Young, potted evergreens make appealing additions to indoor or outdoor holiday decor. Ahead of transplanting, place them on a bench, porch, or to the side of the hearth as festive accents, or decorate them with ribbons, tiny ornaments, and fairy lights for use as a centerpiece or small alternative Christmas tree. How about you? Does English holly warm your heart with its traditional berries and hardiness? Or are you one of the homeowners who’s trying hard to keep it from taking over? We’d love to hear about your experiences via the comments section below, or to field further questions. And if you’d like to learn about some other types that may suit your gardening or landscape needs, here are some helpful holly guides to read next:

How to Plant and Grow Oak Leaf HollyHow to Grow and Care for Winterberry HollyMust-Have Tips for Growing Inkberry Holly