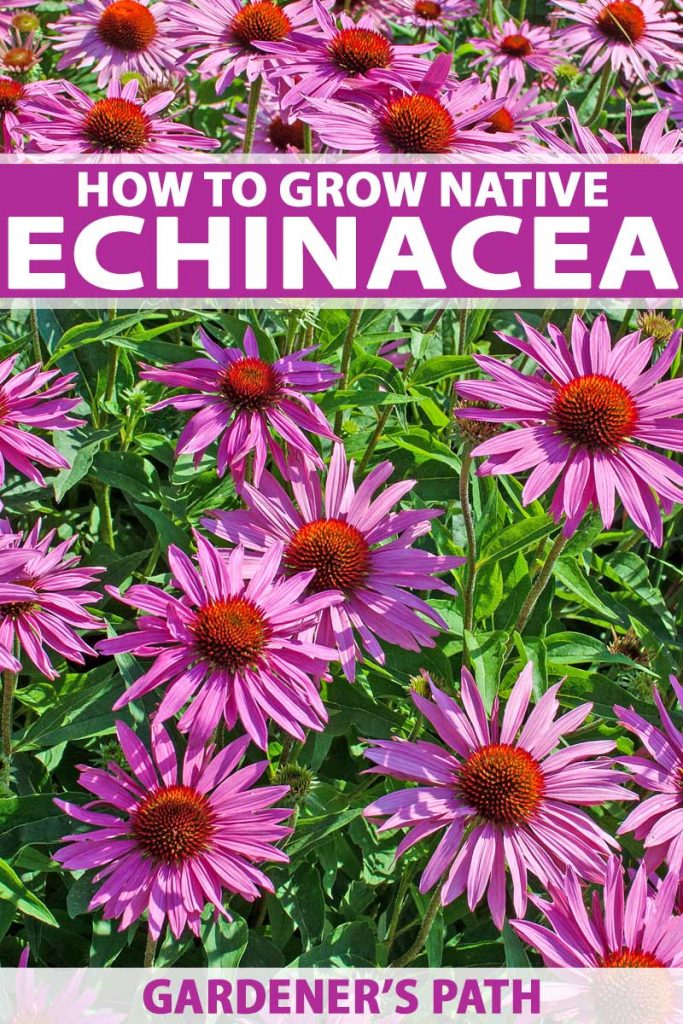

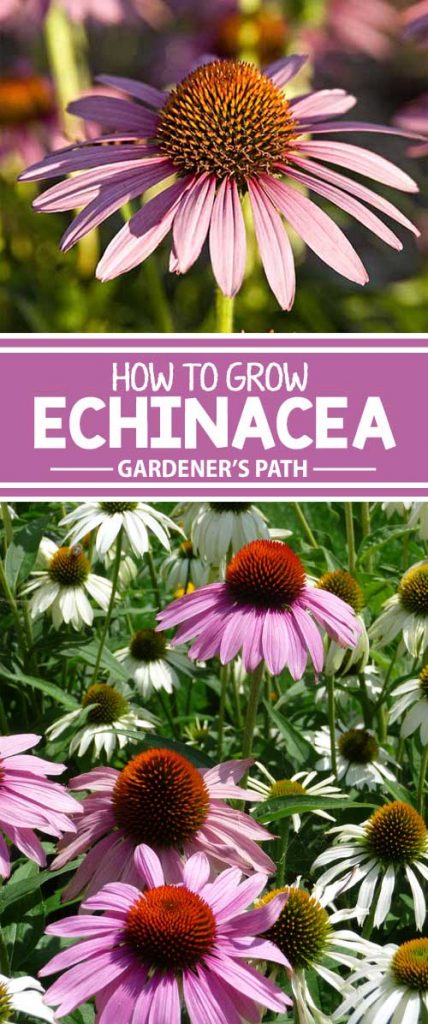

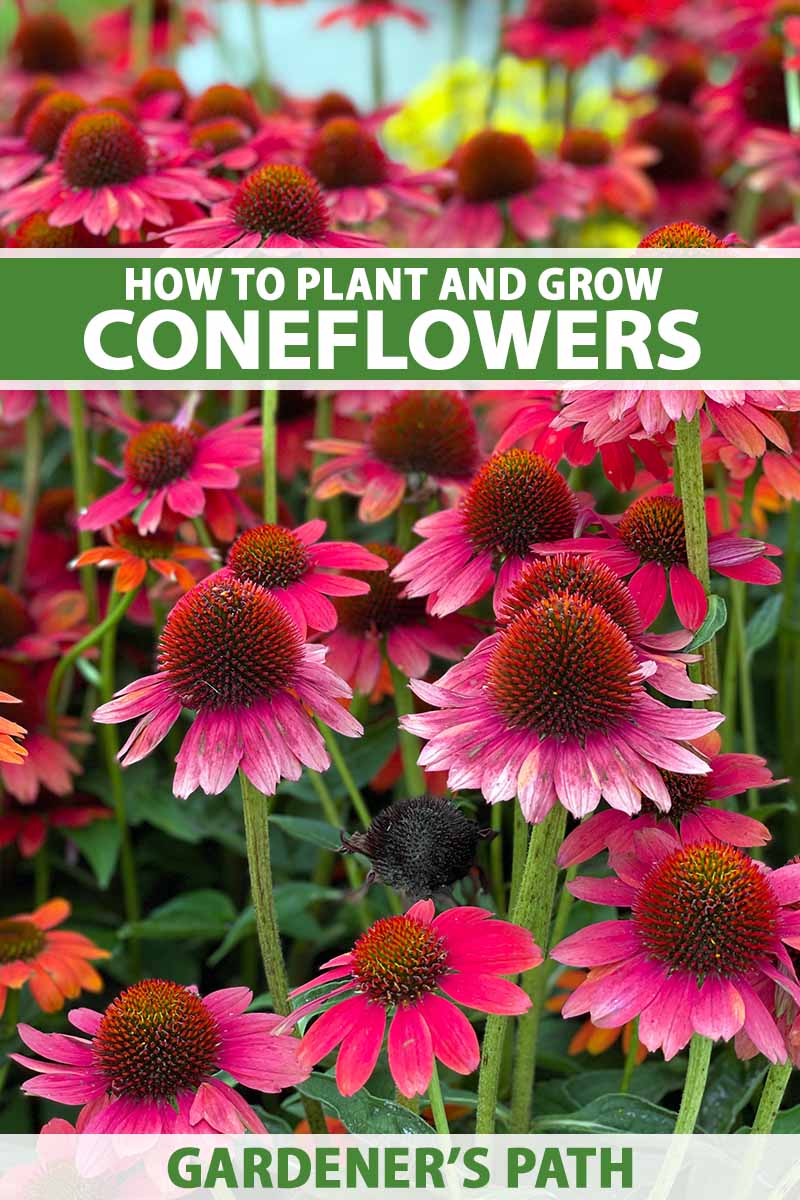

It makes sense, then, that this popular perennial has transitioned from a humble prairie flower to a mainstay across the country. It’s hard to comprehend how many plants we use in the US that aren’t native here. Most of the things filling our gardens come from other places, not to mention the many foreign plants growing in our wilderness areas. But the coneflower is a true American original. Native to the plains region, you can find them growing wild everywhere east of the Rockies except for New Hampshire and Vermont, and they’re cultivated from coast to coast. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. You can even find showy double blossoms if you want something a bit more striking. Whether you’re curious to know how to care for your coneflowers or you want to explore adding them to your garden for the first time, this guide has you covered. Up ahead, here’s what you can expect: Honestly, these plants are so easy to care for that you could plop them just about anywhere and ignore them and they’d probably still thrive. But you want your coneflowers to be the best they can be, right? Then let’s not wait any longer to jump into all the details!

Cultivation and History

Plants in the Echinacea genus are part of the same botanical family as daisies and sunflowers. This family is named Asteraceae, also called Compositae. The botanical name Echinacea comes from the Greek word echinos, which means hedgehog. When you look at the spiky little cone at the center of the petals, you can see why the plant was given this name. The leaves are lance-shaped and alternate, with three or five veins. The entire plant, except for the colorful petals, is surprisingly stiff. The leaves and stems are usually covered in fine, stiff hairs, as well. If you’ve never felt a coneflower leaf, next time you pass a plant, touch one. They are firm and rough, as are the stems and the center of the flowers. Maybe that’s why the Lakota people call coneflowers ica’hpehu, which means “something used to knock something down.” Like other members of the Asteraceae family, the flowers (called capitulas) are actually made up of a cluster of individual blooms called ray and disc florets. Each one of those petals you see is, botanically speaking, a single flower. The ray florets are the colorful petals that line the exterior of the head. The disc florets are the stiff inner parts that stick out of the cone and give the plant its hedgehog-like reputation. They don’t look like traditional flowers, but if you look closely, you can see the extended stigma with little bits of pollen at the top of the flower. If you were to dissect the capitula and pull out some of the disc florets, you can see that they look a bit like petals. The ray florets mature first, followed by the disc florets which mature sequentially in whorls, starting at the exterior. Each day, one whorl opens up at the beginning of the day. In the fall, these florets mature into seeds. If you picture a sunflower, with its halo of yellow ray florets and its center of seeds, it’s the same idea. By the way, the ray florets are just there to attract pollinators with their colorful appearance. They don’t carry pollen and they can’t be pollinated or produce seed. Until recently, coneflowers weren’t admired for their scent. In Potawatomi, the plant is called ashosikwimia’kuk. That roughly translates to “smells like muskrat scent.” This unpleasant aroma seems to apply more to wild species than cultivated types. I took a whiff of several of the E. purpurea cultivars growing in my garden and found them to have a very faint sweet scent if I got up close. However, there are a few cultivars today that have a more enticing scent. ‘Fragrant Angel’ and ‘Tangerine Dream,’ for instance, have a strong, sweet fragrance. All species of echinacea have long taproots except for E. purpurea and E. laevigata. That means these two species do better with a bit more water and they transplant better than others. Species with taproots have long, thick roots that can grow down to eight feet deep and an inch in diameter. There are nine recognized species, though E. purpurea is by far the most common and the one that most of the hybrids and cultivars you can purchase at garden stores are derived from. However, coneflowers cross-pollinate readily with one another, so you will find natural varieties out there that don’t entirely fit the description of one species. The other species include the narrow-leaf coneflower (E. angustifolia), which is one of the most important species for medicinal use amongst native populations and has the largest natural range. It looks similar to the common purple coneflower. Smooth coneflower (E. laevigata) is currently federally listed as endangered. This one has extremely narrow ray florets in light purple to pink, and the stems are smooth rather than hairy. Tennessee coneflower (E. tennesseensis) was once listed as endangered, but conservation efforts have helped bring it back from the brink. You can now find it throughout its native range, which is limited to an area within a 14-mile radius near Nashville, Tennessee. Similar in color to purple coneflower, it stands out because the ray florets are erect rather than drooping as with most other species. Narrow-leaved purple (E. serotina) is native to Louisiana and Arkansas, and has very stiff hairs on its narrow leaves. Pale purple (E. pallida) has pale pink ray florets that are up to three inches long and extremely narrow. Sanguine purple (E. sanguinea) has pink or purple ray florets that droop. Wavyleaf purple (E. simulata) looks identical to the pale purple species and was determined by botanists to be a different species using genetic testing. Yellow (E. paradoxa) has yellow ray florets, and Topeka purple coneflower (E. atrorubens) has deep purple ray florets that fade to pale pink. All species except E. purpurea and E. angustifolia are at some level of risk or considered vulnerable in their native range, and are possibly extinct in some parts of their former range. That’s why many experts caution people not to harvest wild coneflowers unless they are certain of which species they are taking. Since all of these species look fairly similar, it can be hard to tell. Echinacea has been valued for its medicinal uses for centuries, and native people used these plants for a number of different purposes. These uses continue today in most tribes. For instance, according to the book “Native American Medicinal Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary” by Daniel E. Moerman, Blackfoot people chew the roots to ease toothaches, as do Cheyenne tribes, who also use the leaves and roots topically to relieve pain. The Lakota use a poultice of echinacea to reduce swelling, and chew the roots to ease an upset stomach. Omaha populations use the mashed root as a dressing for treating burns and for eye problems, which is why they call it inshtoghate-hi, meaning eyewash. The Pawnee also use it as an eyewash and to treat ailments in horses. The Teton, Sioux, Winnebago, Montana, and Ponca people all also use this plant in similar ways to those described above. The pale purple coneflower is also used by Cheyenne and Dakota tribes for various medicinal purposes, including easing the pain of toothaches and arthritis, treating boils and headaches, preventing thirst, relieving sore throats, alleviating cold symptoms, and healing snake bites. We’ve all been desperate enough to reach for anything in the cold and flu aisle to ease the misery of illness. But most reputable studies so far haven’t found that echinacea has any impact on an existing cold. Native American Medicinal Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary These days, the plant’s reputation as a medicinal wonder has spread far and wide. No doubt you’ve seen store shelves lined with products containing echinacea to treat cold symptoms. It may, however, be helpful in preventing one. The herb also has antibacterial and antioxidant properties. That said, there doesn’t seem to be any harm in using echinacea, especially the stuff you grow in your own garden. Researchers have found that the natural bacteria present and the composition of the soil can impact the efficacy of this well-known medicinal wonder. Using the stuff you grow is doubly smart, since there is no regulatory body overseeing supplements such as echinacea. If you grow it yourself, you can be sure of what you’re getting. However, pregnant women and those with chronic conditions should check with their doctor before using echinacea. It’s not exactly clear when echinacea made the transition from wildflower to popular garden and drugstore feature, but we do know that members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the early 19th century were introduced to echinacea while visiting a Mandan village. Merriweather Lewis sent some coneflower roots to President Thomas Jefferson, who had funded their expedition. The explorers had been asked to send anything back that they considered economically or scientifically significant. Over the course of the next century, it became an important part of the toolbox of early pharmacists and was used to treat snake bites, colds, and flu symptoms. Today, it continues to be one of the most popular medicinal supplements in the US. Many of the plants supplying the trade are grown in India and China.

Propagation

You can start this fantastic flower from seed, nursery starts, stem cuttings, or by division. If your neighbor has an enviable clump or two, take over a homemade chocolate cake or some seeds and cuttings of your own, and ask for a share.

From Seed

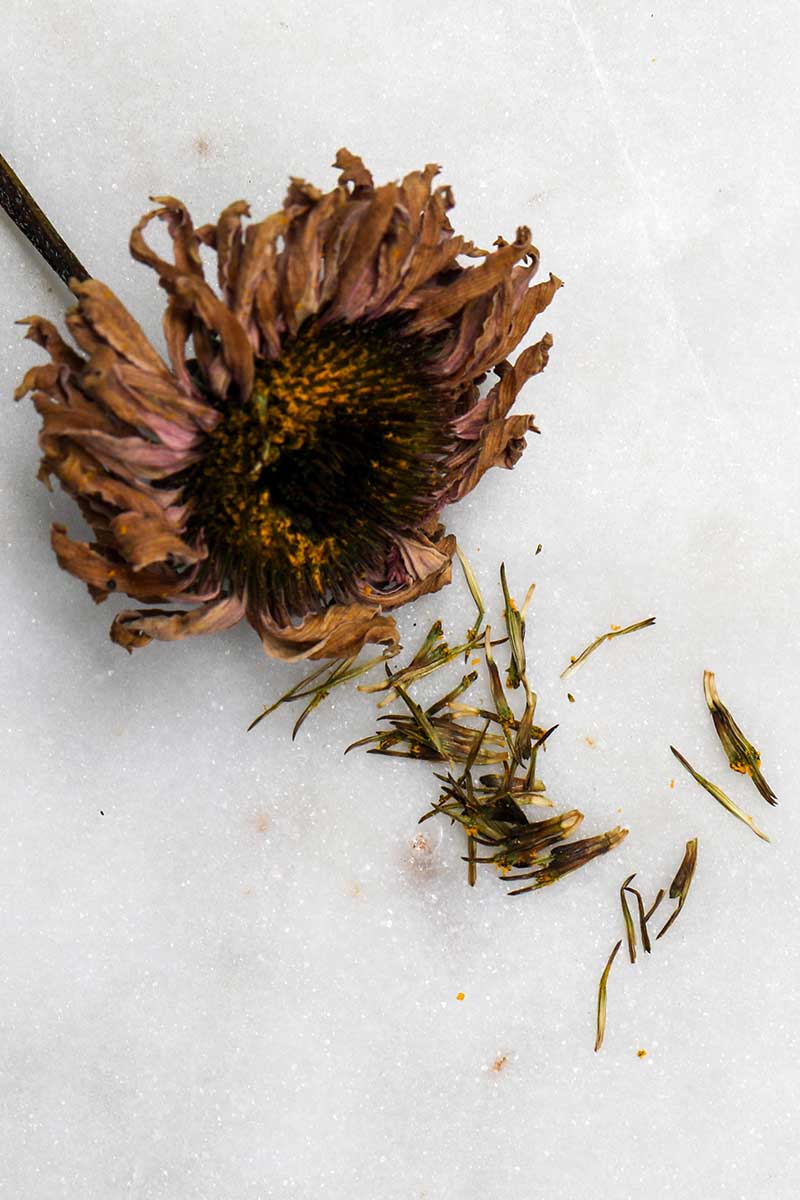

If you’re planting seeds, sow them at a depth of 1/8 inch and expect a 15- to 30-day germination period. Seeds should be spaced 18 inches apart. If you plan to collect the seeds from your coneflowers to plant next year, be aware that these species may hybridize. If you don’t want your purpurea to cross-pollinate with a nearby angustifolia, don’t grow them within a mile of each other. On the other hand, lots of happy accidents have produced some pretty impressive coneflowers. The first known double coneflower, now sold as ‘Razzmatazz,’ spontaneously occurred in a Dutch garden. If you collect wild seeds, be aware that germination rates can be low, with some species growing successfully from gathered seed at rates as low as 10 percent. For the best chance of germination, whether you’re using gathered or purchased seed, put the seeds through a period of cold stratification first. Before you start the process, soak the seeds in water for 24 hours. If you live in an area with temperatures near or below freezing for two months out of every winter, you can simply put the seeds in a rodent-proof container with a mesh or wire top filled with moist sand, and put them outside where they will receive moisture. Otherwise, you can put them in moist sand in a resealable container and place them in your refrigerator for 60 to 90 days. Keep the soil moist (but not wet) at all times. Once you’ve stratified the seeds, you can put them in a seeding medium in seed trays or directly in the garden as soon as the soil can be worked in the spring. The soil should be well-draining. Echinacea prefers cool soil. Too warm and the seeds won’t germinate. That means that a cool basement or garage might be your best bet if you aren’t starting them outdoors. Be aware that echinacea grown from seed might not flower for up to three years, and species other than E. purpurea have a low germination rate. If you’ve started the seeds indoors, don’t put them out into the garden until the seedlings have developed three true leaves and the chance of frost has passed.

From Divisions

Dividing a small plant works reliably with the purpurea species. Other Echinacea species have long taproots, and trying to divide them is a challenge. That said, if you have a large clump, regardless of the species, you can dig part of the clump up and move it to a new section of your yard. Taproot types typically only produce one flower per root, so you can divide a clump with multiple flowers because it likely has multiple roots as well. Keep in mind that if you want to transplant a species with a taproot, you do run the risk of damaging the root. However, a new top will often emerge from any remaining piece of the taproot that’s left in the ground if the plant was mature. Researchers working for the Kansas Biological Survey have found that even when foragers removed the top six inches of the root, a quarter of all the plants they observed resprouted in the first year. To divide, take a spade and shove it down into the soil at the point where you want to separate the plant. Then, dig around the perimeter at the drip line and lift the plant out of the ground. Plant as you would a transplant, and fill the remaining hole with fresh soil.

From Seedlings

Nurseries are overrun with coneflower seedlings during the summer. You can find them in a range of beautiful colors and shapes. Regardless of the species you are growing, it never hurts to work some well-rotted compost into your soil. Compost both improves drainage in clay soil, and increases water retention in sandy soil. To plant, dig a hole slightly wider and deeper than the container that it is growing in. Loosen the sides of the container by pressing them, and then gently pull out the plant. Place the echinacea in the hole and fill in around it with soil. Tamp the loose soil down and water deeply. This settles the soil and gives the plant a good drink.

From Stem Cuttings

Basal stem cuttings can be taken in the spring from new growth. As the plants mature over the summer, the stems hollow out and you can’t use them to take cuttings any longer. In the spring, cut a four- to six-inch-long piece of stem near the soil line. Dip it in powdered rooting hormone and place the cutting in a mix of a soilless potting medium in a six-inch pot. Keep the medium moist, adding more water when the top half-inch of the medium dries out. New roots should form in the next week or so, and new leaf growth should emerge shortly after that. Once you see that several new leaves have formed, you can put the plant out in the garden. Don’t be disappointed if some of your cuttings fail to root. It’s a good idea with this plant to start a few more than you think you’ll need.

How to Grow

One of the many great things about coneflowers is that they aren’t fussy. They prefer full sun, but partial sun won’t phase them. The soil pH should be between 6.0 and 7.0 in a perfect world, but they’ll do fine somewhat out of this range. In the wild, you mostly find echinacea in prairies and disturbed areas like roadsides and abandoned fields. You’ll see them growing in clay, limestone, sandstone, and sandy soil, in forests and in barren areas. That’s a hint about how tolerant they are to a broad range of environmental conditions. Unless you have heavy clay or desert-like conditions in your garden, you should be able to grow this plant. Moisture is another important consideration. They absolutely can’t handle soil that drains poorly, or standing water on their roots. A moderate amount of moisture is ideal, but they can easily survive in some drought. Plants need about an inch of water a week to look their best, so if nature doesn’t provide, you’ll need to supplement the water they receive. Overwatering will deprive the roots of oxygen and cause the leaves to turn brown starting at the tips before the entire plant dies. All that said, cultivated plants in the purpurea species are less tolerant of harsh environments. Their fibrous roots aren’t as well-adapted to drought conditions or low-nutrient soils. If you want to plant coneflowers for xeriscaping, choose a species with taproots. Keep in mind that most advice you’ll find out there on growing coneflowers applies to the purpurea species. Taproot species require less water and fewer nutrients, but they certainly won’t turn down regular water and food if it’s provided.

Growing Tips

Plant in full or partial sun.Provide an inch of water a week.Soil should be well-draining.

Maintenance

Side dress once a year with rotted compost or manure when the flowers start to form in the spring. These plants don’t benefit from lots of added nutrients. You don’t need to deadhead or prune coneflowers necessarily, though there are some benefits to doing so (as well as some potential downsides). Deadheading can encourage new flowers, but it deprives wildlife – and you! – of the seeds. You can divide mature specimens if desired, but it isn’t necessary for the health of the plant.

Managing Pests and Disease

Part of the appeal of coneflowers is that they’re tough. They can survive adverse environmental conditions and are rarely troubled by pests and diseases.

Hot Papaya

‘Hot Papaya’ features vibrant orange and red double blooms, with some of the largest blossoms out there, on a 34-inch-tall plant. ‘Hot Papaya’ To add this standout cultivar to your garden, you can find it available from Nature Hills Nursery in a #1 container.

Magnus

If you want a classic-looking coneflower, ‘Magnus’ is a stunner. It’s easy to see why this one nabbed the “Plant of the Year” award from the Perennial Plant Association in 1998. ‘Magnus’ It has long, pale purple “petals” that last throughout the summer on a four-foot-tall plant. Nature Hills Nursery carries this classic in #1 containers.

Pink Double Delight

While coneflowers are gorgeous for their simple, architectural forms, if you want something a little more frilly and showy, ‘Pink Double Delight’ has hot pink double flowers that are quite large – up to five inches across! ‘Pink Double Delight’ The plant itself grows to about 30 inches tall. Burpee carries live plants if you’re dreaming of adding these pink delights to your space.

Sombrero Lemon Yellow

‘Sombrero Lemon Yellow’ is – you guessed it – a yellow cultivar that almost resembles a small sunflower. This compact plant reaches up to 20 inches tall at maturity. ‘Sombrero Lemon Yellow’ Pop on over to Burpee to purchase a live plant to add a little sunshine to your life.

White Swan

If you like white flowers, ‘White Swan’ is as graceful and snowy-white as its moniker suggests. The blooms can be four inches across and the plant tops out at 12 inches tall. ‘White Swan’ To add ‘White Swan’ to your garden, Eden Brothers supplies seeds in single packets, or ounce, quarter-pound, or one-pound packages. Discover even more of our favorite colorful coneflower cultivars in our roundup.

Herbivores

It’s not often you’ll face herbivore problems with coneflowers. That’s partially because they’re so tough and stiff, and this deters animals browsing for a green to nibble on. The exception is hungry deer. Deer will eat young coneflowers, but only if nothing else tasty is around. Because coneflowers pop up so early in the spring, they can sometimes be one of the only things poking out of the ground. I always put small wire “tents” over my coneflowers until the plants start to mature and, more importantly, until other things have popped up in or near my yard in the spring that I know the deer will go for first. If you need tips for controlling deer in your garden, we have a guide to help you out.

Insects

If you’re growing one of the uncultivated echinacea species, encounters with pests are rare. For purpurea cultivars, here are the insects you might see:

Aphids

Aphids are common garden pests and they’re opportunists. Many of the common species such as green peach (Myzus persicae) or brown ambrosia aphids (Uroleucon ambrosiae) will suck on these plants. They don’t typically cause a lot of damage to echinacea, though they can spread powdery mildew. If you want to be rid of them, our guide to aphids can help. Aphis echinaceae is a specialist aphid that visits uncultivated species. Scientists are currently researching whether or not specialist aphids have a negative or neutral impact on native plants, and preliminary findings show that this aphid species has no negative impact. It’s hard to determine what kind of aphid is attacking your echinacea, but if the aphids that appear on your species plant are light green and you’re gardening in the Midwest, it’s possible that it’s this species. Regardless, unless your plant is showing a negative effect like yellowing leaves, you can leave them alone.

Leafhoppers

The aster leafhopper (Macrosteles quadrilineatus) is a pale green insect with clear wings and six dark spots on its body. While feeding can cause white stippling on the leaves of your plant, that’s not the real concern with this pest. Leafhoppers can also introduce aster yellows, a disease that causes phyllody, which results in abnormal growth. Phyllody is caused by a disruption of the hormones in the plant, which can be driven by infections from viruses, bacteria, or fungi, or insect damage. We’ll talk about this disease a little more later on, but suffice to say that you don’t want these bugs around. Remove all debris in the garden in the fall so these insects don’t have a place to overwinter. You might also want to use floating row covers starting in the early spring if you know leafhoppers are a problem in your area. Assassin bugs will kill the larvae, and an insecticidal spray containing pyrethrin can take down the adults.

Japanese Beetles

Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica) are metallic beetles that are about half an inch long at maturity. They’re easy to recognize with their copper wings, and shimmery green head and thorax. The grubs are white or cream-colored and up to an inch long. When they attack in groups, they can be downright devastating to most plants, but on coneflowers, the damage is usually minimal. They aren’t a preferred meal for the beetles, since the leaves are tough. Still, if you don’t like the look of the holes that they leave behind in the foliage, it’s best to get rid of them. Pick off any that you see and drown them in soapy water. You’ll need to do this every day for a few weeks during an infestation to be sure you got rid of them all.

Disease

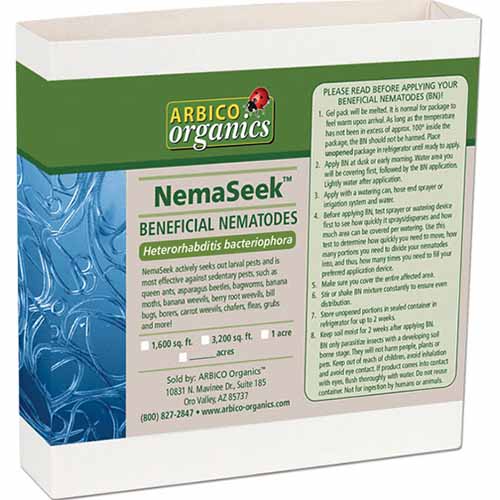

I have never had to deal with diseases on my coneflowers personally, and it’s not because I’m lucky. These plants are simply quite resistant to most problems. Still, they aren’t immune. NemaSeek Beneficial Nematodes You mix it with water and apply it to the soil in the spring, and again whenever the beetles are present. Arbico Organics carries this product in five, 10, 50, 250, and 500 million count containers. Read more about eradicating Japanese beetles from the garden in our guide.

Aster Yellows

Aster yellows is an infection caused by aster yellow phytoplasmas (AYP), organisms similar to bacteria, usually seen in purpurea species plants and cultivars that causes some pretty funky symptoms. Other species rarely contract this disease. The leaves and stalks might be twisted or the ray florets can be discolored. Often, they’ll turn green. The plant can also send up growths from the base of the flowers that look a lot like tiny green flowers. These are actually clusters of leaves at the end of a long stem. The stems might turn red or yellow, and they’ll stop producing flowers. There is no cure, and this disease can spread to other coneflowers or even other plants. Controlling leafhoppers is the best prevention method, and you should dispose of any impacted plants in the trash. I know, it sucks. Read more about aster yellows here.

Fusarium Blight

Fusarium wilt or blight is caused by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. When a coneflower plant is impacted by the fungus, it will have dark patches along the leaf margins. You might also notice that it starts wilting during the heat of the day. Eventually, the leaves turn yellow and may even die off.

Powdery Mildew

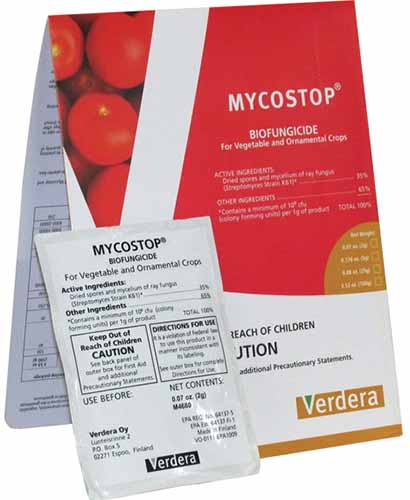

If it looks like your echinacea is covered in flour, your plant probably has powdery mildew (or else someone is playing a prank on you). Mycostop Biofungicide You can buy packages of five or 25 grams of this powerful organic fungicide at Arbico Organics. Caused by the fungus Erysiphe cichoracearum, if left unchecked, it can cause the foliage to turn brown and die. To learn more about treating this common garden problem, though it’s not so common on coneflowers, read our guide.

Best Uses

Coneflowers work well as both container and garden specimens. They’re particularly pretty when paired with things like ornamental grasses, salvia, or members of the daisy family such as black-eyed Susans. Just don’t plant them near anything that needs a ton of water such as fuchsias, irises, sweet woodruff, or daylilies. They also make nice cut flowers for display. To collect seeds, snip off the mature seed heads. The ray florets will turn yellow or brown and then fall off when they’re ready. The heads will swell and become rounder. Put them in a spot with good air circulation to let them dry. Then, gently rub the seeds loose and store them in a paper envelope in a cool, dark place. If you’re growing a double-headed variety, know that you’ll have fewer seeds available to collect. The double head is made up of more ray florets, and with fewer disc florets, plants produce fewer seeds. Keep in mind that hybrid plants won’t grow true from seed. I like to leave the seed heads in the garden for some architectural interest that lasts throughout the winter – or until the birds nab them. If you’d like to use the roots, you have many options. To harvest the roots of taproot species, wait four years for them to mature. Then, dig up the entire plant and cut away the foliage. Clean the root with cool water and a scrub brush. Slice the root when you are ready to use it, otherwise store it whole in a cool, dark place for up to four months. To dry the roots, slice them into half-inch pieces and place them on a screen in a cool, sheltered spot with good air circulation. The roots should be dry and ready for storage in an airtight container in about three weeks. Throw out any pieces that develop mold. A common medicinal method is to make a tincture out of the roots and seed heads. Simply put the fresh or dried plant parts in a jar and cover them with 80-proof alcohol such as vodka. Seal the jar and let it sit in a cool dark spot for a month, shaking it occasionally to agitate the contents. Strain and you’re ready to go. You can also chew on the raw roots. They have a bit of a bite and leave a tingly feeling in your mouth. Scientists have found that taking echinacea supplements can reduce the chances of catching a cold by up to 50 percent! Fresh roots can also be mashed to make a poultice. The flowers can be used to make tea, and you can use the ray florets in salads or to garnish drinks. No word on whether these plains natives will attract bison to your yard, but you’ll certainly have lots of butterflies stopping by. Are you growing coneflowers? Let us know in the comments section below, and feel free to share a picture! And for more information on growing coneflowers, take a look at these guides next:

Tips for Growing Coneflowers in ContainersShould You Deadhead Coneflowers?