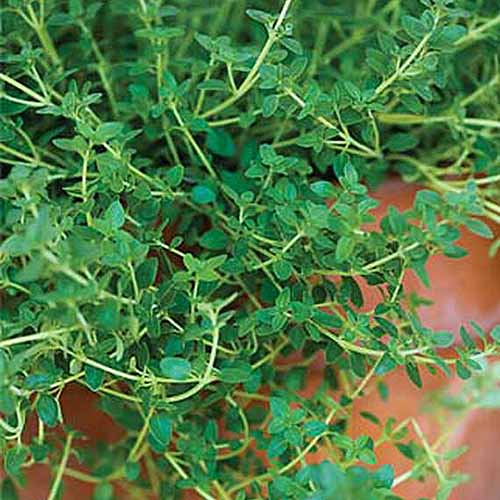

The perennial culinary herb has always been associated with the scents and flavor notes of the season for me because of how prolific it is in my gardens at this time of year. Thyme is a name given to many herbs in the Thymus genus, which is made up of over 350 species, but the most common one used for culinary and ornamental purposes is T. vulgaris, which we’ll focus on here. The three most popular varieties of T. vulgaris are English, French, and German thyme. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Read on to learn about growing this versatile, easygoing herb and its long and storied past.

Cultivation and History

Thyme has been utilized by humans for over two millennia, and its existence as a species predates homo sapiens, with evidence discovered in fossil remains that are over five million years old.

One of the earliest known uses of this herb was in ancient Egypt, where it was used for embalming the dead and was thought to assist them on their way as they passed on to the next life. Ancient Romans believed it to be a useful antidote to poison. Emperors would often include this herb in their meals and even scented their baths with it. It was also during this era that it was established as a symbol of courage. Later, in the Middle Ages, soldiers were often given bouquets that included thyme as they were sent into battle. And prior to the advent of modern medicine, due to its natural antiseptic properties, thyme oil was used to medicate bandages. What was little understood then can be confirmed by science today, with the active ingredient thymol showing distinct antibacterial activity in studies. T. vulgaris has also been hybridized with other species in the genus to create new varieties including my own personal favorite, lemon thyme (T. citriodorus).

Propagation

Thyme can be propagated easily from cuttings, layering, divisions, or seeds.

From Cuttings

Simply take a three-inch cutting from the tip of a stem and remove the lower third of leaves from the cutting.

While not mandatory, rooting hormone can be applied, which will increase the speed of rooting and your chances of success. Whether you use gel or powder, remove just enough from its container to dip the bottom third of the cutting in so as not to contaminate your rooting hormone. To prevent any bacterial or fungal infections, plant the cuttings in a well-draining, sterile potting medium one inch deep. You can use sterile sand mixed with one-third potting soil or vermiculite, for example, or cactus potting soil. Make the hole first with your finger so you don’t rub the rooting hormone off in the soil, submerge the cutting, gently tamp the soil around it, and water. At this time, you can transplant the newly rooted plants to a suitable place outdoors or into four-inch pots.

Viagrow Humidity Dome To minimize watering requirements and maintain a moist environment I recommend the use of a humidity dome like this one from Viagrow, available at Home Depot. By the time you see new growth, roots should also be emerging, which will take about four to six weeks. When planting outdoors, the best time to transplant is in springtime after the last frost. Space them 12 to 24 inches apart throughout your landscape as companions to other plants, or as part of your herb garden.

By Layering

As soon as the stems hit the ground, they begin sending out roots. This makes them perfect for layering. Take a long stem and simply secure it to the soil with a stake, which can be fashioned from a small branching or V-shaped twig, ensuring that there are at least four inches between the tip of the stem and the stake. The tip will begin to grow upright from the stake, and in about a month, sufficient roots will have formed. When the plant seems securely rooted, sever the rooted stem from the rest of the plant, dig up your new plant, and transplant it into an appropriate space in the garden or into a four-inch pot.

Via Divisions

If you’re growing your T. vulgaris in a container, this technique may work best for you, but divisions are also possible from garden plants.

Look for stems that are woody. These will be your main branches that will serve as the initial trunks of the separated pieces. Thyme roots are fairly shallow, so you’ll be able to easily unearth them by digging under the plant by less than a foot. Get at least two stems per section of roots and use a sharp knife to cut the roots from each section you’re dividing. Plant these new plants at least 12 inches apart in the garden or in four-inch pots, ensuring that the root system of each is completely buried beneath the surface.

From Seed

Thyme grows moderately well from seed, which you can purchase or harvest yourself.

Garden Rich Root & Grow To help plants become established, fertilize with a transplant fertilizer like Garden Rich Root & Grow from Bonide that’s available from Home Depot, following the instructions on the package. Learn more about dividing perennials in this guide. Harvest seeds from plants in the fall once flowers have dried up and seed heads have turned brown. It’s best to germinate seeds indoors in a controlled space at around 70°F, in indirect light. To start from seed, prepare trays with moistened seed starting mix. Surface sow or just barely cover seeds, planting at least five times more seeds than the total number of plants you wish to grow, as germination can be erratic. Keep the soil moist but not soggy, watering the seeds with a spray bottle or the misting attachment on a hose to ensure that the seeds are not flooded with the deluge from a watering can. It takes around 14-28 days for seeds to germinate. Once the seedlings are about four inches tall, with around four true leaves, they are ready for transplanting into their permanent container or garden location. Keep young plants well-weeded, especially as they become established, as they can be easily overwhelmed by larger, more aggressive plants.

How to Grow

Thyme is drought resistant and thrives on neglect. Originating from the Mediterranean, it typically grows on dry, sandy, and/or rocky well-draining soil in the wild, in full sun.

As with all plants, the closer you can come to recreating the conditions of its natural habitat, the better it will do. This plant needs little if any fertilization. In fact, fertilizing with too much nitrogen may cause faster growth at the expense of flavor. Although many sources list T. vulgaris as growing only in Zones 5 and up as a perennial, other sources confirm my own experience that certain varieties can grow outdoors year-round in Zone 4, or even Zone 3.

Neptune’s Harvest Fish Fertilizer Neptune’s Harvest fish emulsion, available from Arbico Organics, would work nicely. As always, make sure not to overfertilize and consider testing your soil before indiscriminately fertilizing your plants. Thyme prefers a neutral pH but will tolerate soil that’s between 6.5 and 8.5 on the pH scale. This plant also does well indoors as long as it receives at least six hours of direct light per day, with eight hours being ideal. When cultivating in a container, a low strength fertilizer such as AgroThrive™ General Purpose Fertilizer, available from Arbico Organics can be applied once per month.

AgroThrive™ General Purpose Fertilizer Thyme should be protected with a heavy mulch in colder climates in USDA Hardiness Zones 4-6 to survive the winter outdoors.

However, it is even more important in colder zones to plant plants in sandy, well-draining soil as thyme hates being embedded in ice when the ground freezes – something I learned the hard way when I lost all my plants in a silty part of my garden one winter. Thyme is known to grow quickly, especially the creeping cultivars. Ensure that plants are spaced at around 12 to 24 inches apart, depending on the specific variety.

Companion Planting

These plants are good neighbors. They are thought to provide natural pest control with their aroma and essential oils, and they attract pollinators when they’re in bloom.

Good companion plants for thyme include:

Brassicas

Members of the Brassica genus such as cabbage, kale, brussels sprouts, broccoli, and cauliflower are susceptible to aphids, flea beetles, cabbage moths, cabbage loopers, and cabbage worms, which are thought to be repelled by thyme. It also attracts beneficial insects such as ladybugs that feed on aphids.

Nightshades

Nightshade plants such as tomatoes, eggplant, and potatoes are prone to certain pests that thyme repels. It attracts hoverflies and ladybugs whose larvae eat aphids, and parasitic wasps whose larvae eat tomato hornworms, for example. Thyme is also said to enhance the flavor of these crops, though I could find no studies supporting this.

Roses

Roses are often attacked by aphids and black flies, which may be controlled by ladybugs and parasitic wasps that are attracted to thyme.

Strawberries and Other Fruiting Plants

As an excellent ground cover, T. vulgaris helps prevent weeds from choking out strawberry plants. It also keeps moisture in the soil by providing a living mulch that helps to prevent water evaporation. Thyme is also known to ward off damaging worms, such as corn earworms and cabbage worms. In fact, because this herb attracts and supports many types of pollinators when it is in bloom, it works well near any fruiting plant that is pollinated by insects, including the nightshades described above, fruit and nut trees, and more.

While it certainly sounds like the Miss Congeniality of herbs, note that any plant that requires especially moist soil should not be planted with thyme, since it doesn’t do as well in overly wet soil.

Growing Tips

Grow in a full sun location. Plant in well-draining soil. Water only when the soil is dry.

Pruning and Maintenance

Pruning thyme encourages new growth and branching, which gives you a fuller plant. Generally, the more you trim your plant, the faster it will grow.

However, never cut more than one-third of your plant in a one-month period during the growing season, and always leave at least five inches of growth intact. Thyme also needs to be weeded more often than some plants since it doesn’t grow very densely and its leaves are relatively small, casting little shade to block out the weeds.

Cultivars to Select

Diseases are also rare if planted in well-draining soil, but fungal diseases can be a problem occasionally.

English/Common

As its name suggests, English or common thyme is the most common variety of this species in cultivation, and it is often sold dried for culinary use. If not otherwise indicated, recipes generally call for English thyme. It is best used for seasoning meats and stews and is known to have a stronger flavor than the German or French varieties. Like most other T. vulgaris varieties, the English type has small light purple flowers, though it has slightly pointier leaves than the other varieties, and a reddish stem.

Common Thyme It grows five to 18 inches in height with a spread of up to 16 inches and is suitable for Zones 4-8, though some sources list it as growing best in Zones 5-11. Potted plants in sets of three, or packets of 1800 seeds are available from Burpee.

French/Summer

Often used in French and French-influenced cooking, this is the type used in herbes de Provence blends. With a subtler flavor profile than its English counterpart, French thyme is more suited to cuisine requiring more delicate flavors such as seafood and quiches. It’s known to have a more pronounced sweetness and slightly less mint and clove notes than the others.

French Thyme French thyme grows eight to 12 inches tall and wide, is less cold hardy than German and English types, and is suited to USDA Hardiness Zones 5-11. Seeds are available at True Leaf Market and packs of four plants in quart-sized containers are available at Home Depot.

German/Winter

German thyme is very similar to the English variety, though it’s slightly more cold hardy, has more rounded leaves, and lacks the red stem of English and French types. Its flavor is less intense than that of the English type, though not as subtle as the French.

German Thyme German thyme grows 12 to 18 inches high and wide, and is at home Zones 4-9, though some sources say it can be grown down to Zone 3. Plants are available from Home Depot.

Managing Pests and Disease

Thyme does not tend to be bothered by insects much, though the most likely pests are spider mites and aphids.

Insects

I have never seen insects of any kind bothering my thyme plants, but others have reported the possibility of aphids and spider mites becoming a problem.

Aphids

These small white, brown, or black bugs tend to gather on the underside of leaves or on the tips of stems. They weaken plants by sucking out their juices and can spread disease through their saliva. A scrub down with one part rubbing alcohol and one part water using a cloth, followed by an insecticidal soap or neem oil spray is effective and should be done weekly until they are gone. Read more about fighting aphids in your garden here.

Spider Mites

Spider mites, as their name implies, are small spider-like mites. It’s easy to tell if your plants have spider mites as there will be a fine web covering their leaves andstems. They suck the juices out of your plants as well and can be controlled in the same manner as aphids.

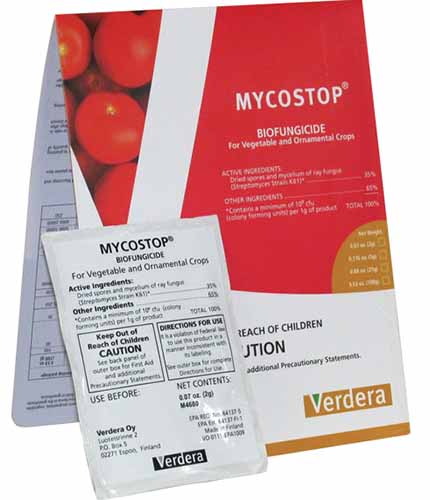

Disease

Thyme is most commonly affected by fungal diseases, including botrytis rot (Botrytis cinerea), root rot (Rhizoctonia solani), and Alternaria blight (Alternaria brassicicola). Warm, damp conditions often encourage the growth of these fungi. Treatment options for these fungal diseases are similar, and include the following:

Remove infected areas using sharp, clean scissors, pruning shears, or a knife. Bottom water plants via trays placed under your pots, or at the base of the plant without getting any water on leaves. Prune and/or stake your plants into an upright position to improve air circulation. Mulch underneath the plants, to prevent fungal spores in the soil from splashing onto the leaves. Provide supplementary irrigation infrequently, if at all, and only in the early morning if needed, to allow soil time to dry during the day. If your soil is not well-draining, consider transferring your plants to a different location with more suitable soil, preparing it ahead of time if needed by amending with sand and/or perlite.

Harvesting

You can snip off sprigs of thyme as needed. However, a mass harvest can be done yearly during the summer. Pick right before the flowers begin to bloom for the best flavor.

Mycostop Biofungicide For more serious cases, you may want to consider using a biofungicide such as Mycostop’s mycelium-based fungicide available from Arbico Organics.

The best time of day to harvest is early in the morning, after the dew has dried. This is the time when the aromatic and flavorful essential oils are the most concentrated.

Preserving

Fresh thyme lasts about a week, but it can be preserved for months – or even longer. Nothing beats the flavor of fresh herbs, but when you have too much harvest to use fresh or the season is ending, you can preserve this versatile herb by drying, freezing, or infusing it in oil. Our sister site, Foodal, has a helpful guide to making tasty herbed oils.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Not only is thyme delicious, but it’s also packed with an impressive list of vitamins and minerals.

It’s rich in vitamins C and A. It also contains fiber, iron, manganese, copper, calcium, and riboflavin. Thyme is a culinary mainstay around the globe. Used in both fresh and dried form, this herb can withstand long cooking times and high temperatures and maintain its flavor. Learn more on our sister site, Foodal. It’s used as part of bouquet garni in French Provençal cooking, dry rubs for English roasts, in Arabic stews, and even in desserts.

Landscape Uses

While thyme is best known for its culinary uses, it’s also a beautiful plant that fits beautifully in a fragrant ornamental garden.

In landscaping, thyme serves as a fast-growing ground cover or a border plant for the front of your beds. As mentioned above, they also make great companion plants, deterring pests and attracting bees that help pollinate neighboring plants and ladybugs that eat pests like aphids.

Medicinal Uses

Traditional medicinal uses of thyme include the treatment of depression, epilepsy, nightmares, headaches, and coughs – and many of these uses now have scientific backing. Some research has shown that certain active ingredients in thyme such as thymol and carvacrol have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiseptic properties. At least one study even showed that an extract exhibited antiviral activity against respiratory viruses. A compound called thymol extracted from thyme oil is also an active ingredient in commercially available mouthwashes, and is used in hand sanitizers and acne treatments for its antibacterial properties. Whether you go for the classic English thyme with its more potent flavor, the more subtle flavored French type, the hardy German variety, or other hybrids, this herb has a lot to offer in your garden and your kitchen.

If you already grow it, I’d love to hear about your good (or challenging) times with thyme. Leave your photos, comments, or questions below! And for more information about growing herbs in your garden, check out these guides next:

The Top 5 Mediterranean Herbs: Growing, Eating, and Healing Spring Care Tips for Your Herb Garden Tips for Growing Herbs in Containers

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Arbico Organics, Burpee, and Home Depot. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. The staff at Gardener’s Path are not medical professionals and this article should not be construed as medical advice intended to assess, diagnose, prescribe, or promise cure. Gardener’s Path and Ask the Experts, LLC assume no liability for the use or misuse of the material presented above. Always consult with a medical professional before changing your diet or using plant-based remedies or supplements for health and wellness.