It’s related to the native burning bush, E. atropurpureus, as well as native bittersweet, Celastrus scandens, and its highly invasive non-native counterpart, C. orbiculatus. The non-native burning bush, E. alatus, is not to be confused with Mexican fireweed, Bassia scoparia, which is considered an invasive plant in several states. Although it is an herbaceous plant and not a woody shrub, it too is commonly called a burning bush. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Non-native E. alatus grows in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 8. It can reach heights of 15 to 20 feet with a spread of eight to 12 feet. Compact varieties may be as small as six to eight feet tall and four to six feet wide. Let me explain. Growing non-native plants is often frowned upon because they can become invasive, taking over the landscape, choking out native plants, and doing little to nothing to support endemic species. Although, in all fairness, there are highly aggressive native plants that can do the same thing, like smooth sumac, Rhus glabra. But I digress. Across almost half of the United States, from the Northeast to the South and Midwest, E. alatus is classified as invasive. And in some states, like Massachusetts and New Hampshire, it is actually banned, due to the potential for prolific spreading via seed dispersal. There are numerous Euonymus species related to E. alatus. Unfortunately, many have invasive tendencies, like E. grandiflorus and E. europaeus, which have deep purple autumn leaves, as well as the equally invasive ground cover E. fortunei, also known as winter creeper. Why are we going to tell you how to grow an invasive plant? Because for more than half of our US-based readers and a great many of our international ones, E. alatus is not considered problematic. Please check with your local agricultural extension to determine if there are restrictions on planting non-native burning bushes in your region before attempting to do so. For those folks in regions with restrictions, we offer an alternative species, a burning bush that’s native to the Eastern United States, E. atropurpureus. You may find it is often called the Eastern or American wahoo. This native species is very similar to its non-native cousin, with regard to cultural requirements and size. A dull red shade, this plant’s best feature is its ornamental fruit. E. atropurpureus thrives in Zones 3 to 7, and supports biodiversity and local wildlife. Mature dimensions are 12 to 20 feet tall and 15 to 25 feet wide. For our readers in locales without restrictions, you have the option to plant either type. Regardless of your choice, this article will guide you in planting and caring for burning bushes, both non-native and native. Here’s what’s in store:

Cultivation and History

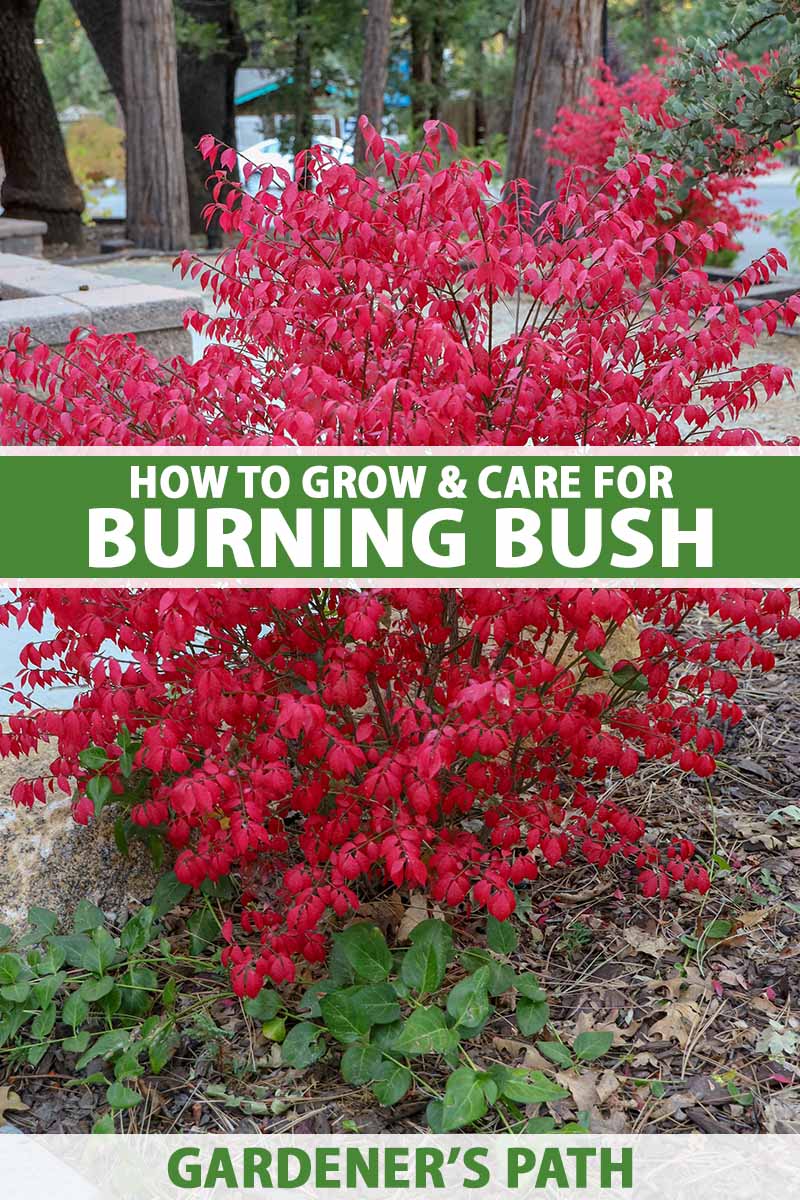

The showy burning bush, E. alatus, is of Asian origin, and was likely imported to North America in the 1860s to be used as an ornamental garden specimen. It is one of over 170 species of Euonymus, which in some regions, such as the United Kingdom, are commonly called “spindle trees.” Among them are deciduous trees and shrubs, as well as evergreens and ground covers. In addition to burning bush, E. alatus is also known as winged euonymus, winged burning bush, or winged spindle tree, because of a unique feature of the stems. They have flattened extensions like little propellers, which are described as corky and wing-like. Historically, Euonymus stems were prized for use as knitting needles and thread spindles, hence the common name. What wasn’t clear when these plants arrived on our shores was that they would jump their manicured beds via self-sowing, and over time, North American birds would recognize the fruits of these foreign shrubs as food, and contribute to widespread seed distribution. Fast-forward to today, when nearly half the nation has experienced disruption to native plantlife thanks to this deceptive autumn beauty that makes it impossible for endemic species to compete for survival. Again, I’d like to reiterate the importance of contacting your local agricultural extension for advice and information about possible restrictions before planting. Prior to their spectacular autumnal display, burning bushes have elliptical green leaves, and nondescript greenish-yellow blossoms appear in early spring. In addition to their fall colors, burning bushes have pinkish pendant or hanging fruits that open like flower petals to reveal orange-red arils containing black seeds. While they may have had a historical role in Native American medicine, the fruits are toxic and should not be consumed by people or pets. As the weather cools in the fall, the green foliage of summer shades to scarlet. The fruits drop off, scattering seeds that will sprout next year. This deciduous shrub then drops its leaves, revealing bare “winged” stems that add structural and textural interest to the coming winter landscape. Now, let’s look at how to start growing a shrub at home.

Propagation

Although the burning bush produces seeds, cultivated varieties that are hybrids of two or more different species may not reproduce “true,” resulting in progeny that varies in quality and physical traits. In addition, propagating seeds is the slowest way to start a new shrub. Faster and better ways to begin are with soft wood cuttings, or starter plants purchased from a nursery. Here’s how:

From a Cutting

In early summer, when the first flush of new growth is well underway, you can take cuttings from the growing tips of an established shrub for rooting. Use clean pruners to snip off a length of stem that’s about four or five inches long. Pinch off the lower leaves so that the bottom three inches of the stem are bare. Dip the freshly cut stem into rooting hormone powder. Fill a six-inch-deep, well-draining container about three-quarters full with a sterile potting medium. Make a three-inch-deep hole in the center of the potting medium with a pencil or dibber. Place the dipped stem in the hole and tamp the medium securely around it. Water well, and thereafter whenever the top two inches of the soil feel dry. Use a moisture meter to help with this task. Tamp the soil down and water until it drips out the bottom of the container. Water a second time, and when the draining stops, place the pot in a sunny place, either indoors or outdoors. New growth is evidence of rooting success and readiness for planting in the ground. When the cuttings are ready, prepare the garden soil by working it down eight to ten inches until it is friable, or crumbly. Unpot the rooted cutting and settle it into the soil so that its crown, where the roots and stem meet, sits slightly above ground level. Backfill, tamp the soil down, and water. Apply a one-inch layer of mulch around, but not touching, the transplanted cutting to aid in moisture retention, keep weeds down, and insulate the root zone.

From a Transplant

Early spring and fall are the best times to plant a nursery shrub. When you buy one, it may be about 18 months old and sold in a quart-size pot, or two years of age or older and growing in a two-gallon container. To transplant, use a long-handled, pointed garden shovel that you can step on. Dig a hole at least twice as wide and twice as deep as the pot the shrub is in. Work the shrub out of its nursery pot, and gently loosen the roots. Place the shrub into the hole so that the crown is slightly above ground level. Refill the hole, taking care to keep the shrub vertical. Tamp down and water well. Apply a three-inch layer of mulch in a circle around the shrub. It should start about four inches away from the stems to avoid rot and extend out about 10 inches, to help retain moisture and keep the roots cool.

How to Grow

E. alatus and E. atropurpureus grow best in full sun to part shade. These species can tolerate full shade, but the color will not be as vibrant. The ideal soil is of average quality, drains well, and has a pH of 6.0 to 7.5. However, a variety of soils and pH levels may be tolerated, provided the drainage is good. To understand your soil, contact your local agricultural extension about conducting soil tests for the various parts of your landscape. Where acidity is too great, lime is often all that is needed to “sweeten” soil, and conversely, where alkalinity is higher than desired, the addition of compost or aged manure may be all that’s needed. To plant a single shrub, choose a location with room for a mature spread of eight to 12 feet. If you’re going to create a hedge, closer spacing of five to six feet is acceptable. If you have black walnut trees, don’t worry. This shrub tolerates juglone toxicity. Transplanted cuttings and nursery plants need even moisture during their transition to the landscape, but should never be in soggy ground. Once established, they require an inch of supplemental water each week, in the absence of rain. The growth rate of a burning bush is about one to two feet per year. Mature shrubs have above average drought tolerance.

Growing Tips

There’s not a lot to remember when you grow your own shrub. The following tips will put you on the road to success:

Maintain even moisture when rooting cuttings, and transplanting cuttings and nursery starts to the landscape.Provide a location with full sun, or sacrifice some color in shaded locations.Be sure that your soil, whatever type it is, drains well.Remember that E. alatus is a prolific self-sower that is considered invasive in almost half of the US. Native E. atropurpureus also self-sows with vigor.In rare instances, burning bushes may not turn red. We cover this in a separate guide.

Pruning and Maintenance

E. alatus, and its native counterpart E. atropurpureus, are low-maintenance garden residents. In early spring, rake away any remaining bits of last year’s mulch. Apply a well-balanced, all-purpose, slow-release granular fertilizer per package instructions. I usually sprinkle it in a ring around mine, and then lightly water it into the soil. While the soil is still moist, apply a new three-inch layer of mulch, remembering not to let it touch the stems. Other than that, maintenance needs are minimal. Use clean pruners to cut dead branches, so your shrub can refocus its efforts on feeding the healthy ones. Prune off any damaged branches and remove all debris, to avoid attracting and harboring pests and pathogens. In addition, you may want to prune your shrubs to maintain a formal hedge, or remove wayward branches such as those that block a walkway, for example. And if naturalizing plants via self-sowing is not what you have in mind, you’ll want to be vigilant about plucking unwanted seedlings in the spring.

Cultivars to Select

If you buy a non-native shrub, you will receive a cultivated variety that has been developed from one or more species for landscaping use. And as there are no sterile cultivars available to date, self-sowing is to be expected. Here are two varieties to consider growing in regions where they are not prohibited:

Managing Pests and Disease

When it comes to anticipating issues with insects and pathogens, there are few to worry about with E. alatus. ‘Chicago Fire’ Like the glowing embers of an autumn bonfire, the scarlet foliage of this type adorns branches that rise to mature heights of eight to 10 feet with a spread of six to eight feet. Find ‘Chicago Fire’ plants from Nature Hills Nursery now in #3 containers.

Compactus

E. alatus ‘Compactus’ lives up to its name as a smaller version of this fall favorite. Nature Hills Nursery offers it under the name ‘Compacta.’ ‘Compacta’ Topping out at a moderate six to eight feet tall with a spread of four to six feet, this type offers the small-space gardener the opportunity to enjoy a specimen planting that won’t overwhelm a garden scheme. Find ‘Compacta’ plants from Nature Hills Nursery in #3 containers. Nature Hills Nursery employs Plant Sentry™ to block shipments to areas where this shrub is prohibited. If you are interested in growing native E. atropurpureus, please contact your local native plant society for sourcing information. In the event of severely dry conditions, spider mites may pose a threat. You can read about detecting and controlling spider mites in our guide. Taking care of infestations is important, especially as they may spread plant diseases with their piercing mouthparts. On the flip side, conditions that are too wet may also invite trouble, in the form of a disease called twig blight. This condition causes the thinnest stems at the tips of woody plants to die back, and is caused by parasitic Cytospora fungi that winters over in plant debris and activates with wetness. It may be accompanied by chlorosis, or yellowing of the leaves. Pruning off affected branch portions and treating with a fungicide early in the season may restore good health. Also, Euonymus plants in general are prone to powdery mildew, a fungal condition that may be treatable with a copper-based fungicide. As for native E. atropurpureus, there are also few pest and disease concerns. One pest that favors it is scale, a sap-sucking insect that secretes sticky honeydew, leaving a trail that is prime breeding ground for a fungal condition called sooty mold. You can learn more about scale here. And finally, you might want to read up on deterring deer, because they find the foliage of both E. alatus and E. atropurpureus to be very appetizing.

Best Uses

Burning bush makes a striking stand-alone specimen, especially when cloaked in its signature scarlet. It also makes an eye-catching focal point when it stands in contrast to green shrubs in a mixed group. The dense branches of E. alatus make an outstanding formal or informal hedge when planted around patios and along property perimeters. E. atropurpureus has airier branches that are suited to informal, unmanicured hedging. And if you need to soften the sharp edges of architectural elements, like walls and fences, burning bush fits the bill, merging garden spaces and building materials with dramatic effect. Where it is not classified as invasive, you can let shrubs of either species naturalize to create an expansive drift that explodes into a profusion of crimson every fall. If you live in a locale where E. alatus is prohibited for its invasiveness, or even if you don’t, consider planting native E. atropurpureus instead, and help support biodiversity and wildlife that depend upon endemic plants for their survival. You’ll find more information about choosing native alternatives to non-native shrubs in “Midwestern Native Shrubs and Trees” by Charlotte Adelman and Bernard L. Schwartz, a book we have reviewed and that you can read about here. If you grow burning bushes and would like to share your thoughts, or if you have any questions that we can help with, please leave us a message in the comments section below. We hope you’ve found this guide informative. For further reading on creating a robust fall landscape, we suggest the following:

11 of the Best Cold Temperature Ornamental Plants for the Fall Garden15 of the Best Woody Shrubs for Fall ColorFall Garden Planting Design Guide: Create a Cozy & Inviting Autumn Oasis