But it wasn’t just any sand. It was sand my dad had brought back from a trip to Honduras for me, to sate my obsession with turquoise-watered and white-sanded beaches. I wanted nothing more than to take a dip in the clear, warm waters of the Caribbean. When I was thirteen years old, my wish came true. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. And I was also introduced to a thrilling array of plants and fruits I’d never seen before: slimy-sweet guineps, purple-white star apples, stately birds of paradise, and violet clumps of agapanthus.

The orchards and gardens of the island were unforgettable. Sadly for me, most of the gorgeous vegetation that flourishes in warm places like Jamaica fails to grow here in Alaska. But many of these plants thrive in places where my family lives, like southern California and Arizona. And if you live in USDA Hardiness Zones 6-11, this guide can help you try your hand at growing graceful, cheery agapanthus flowers. Here’s what I’ll cover:

What Is Agapanthus?

The name Agapanthus comes from the combination of the Greek words agape (love) and anthos (flower). So they’re pretty much a love flower. Flower of love. Lovely flower. You get the idea. With their lance-like leaves and tall, three-foot stems, spring- and summer-blooming agapanthus reminds me of allium flowers – which makes sense, since they’re in the same botanical family.

They also remind me somewhat of lilies, with their upright stalks and round umbels of trumpet-shaped blooms. And I’m not alone. Though they’re not in the same family as lilies, agapanthus are often called “lily of the Nile” or “African lily.” In South Africa, they’re also called blue lily, isicakathi by the Xhosa people, and ubani by the Zulu. The first reason for these names is that the flower is native to the southern African countries of Swaziland, Mozambique, South Africa, and Lesotho; the second is that in the 1900s, botanists originally classified the appealing flower as a member of the Liliaceae family. But it’s now recognized as belonging to the Amaryllidaceae family, which has three distinct subfamilies: The most prominent species within the lonely Agapanthus genus are A. africanus, A. praecox, A. orientalis, and A. inapertus. Dozens of cultivated and naturally occurring hybrids are derived from these species. Most cultivars feature blooms in shades of blue, violet, and white.

Depending on the species, foliage can be deciduous or evergreen. And while the flowering plant is native to southern African countries, it has naturalized all over the world, including in the United States, Jamaica, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, and the UK. In fact, this plant naturalizes and spreads so well and is so resistant to pests, disease, and death in general that some gardeners consider it a weed.

But others value its tenacity: in hot desert regions of the world, it’s often the only green for miles. It’s also somewhat fire-resistant. While it does burn eventually, the thick, sap-filled leaves take a long time to do so. A border of agapanthus, therefore, has been known to help slow a fire. Plus, it’s hard to deny their beauty. A pathway bordered by the vibrant, globe-shaped blooms is quite divine indeed.

Cultivation and History

Not much is known about the history of this plant, but at some point in the middle of the 17th century traders brought evergreen varieties from the southern African coast to Europe – and later to the US. In the 19th century it was introduced to Australia and New Zealand.

The deciduous type of agapanthus wasn’t discovered by colonists (though it was well-known to local people) until the early 18th century. Unlike the coastal evergreen variety, deciduous species grow wild in the mountainous regions of southern Africa. As a result, deciduous cultivars thrive in areas with cooler winter temperatures. Think USDA Hardiness Zone 6. But evergreen cultivars suffer in any type of cold and are best grown in Zones 8 through 11, unless you’d like to keep them as houseplants for part of the year. While evergreen varieties can’t stay outside during the winter, they make excellent indoor potted plants during the cold season.

People in some cultures use the rhizomatous root system for medicinal and spiritual purposes. Xhosa women of South Africa make a necklace out of the roots to help keep pregnant women and their unborn babies safe from harm. Zulu women put the plant’s anti-inflammatory properties to good use by making traditional medicine to alleviate chest pain, heart disease, coughs, and edema.

Propagation

The two ways to propagate agapanthus are from seed and by root division. It takes some patience to grow them from seed, as they won’t flower for two to three years.

Bear in mind that seeds saved from an existing plant won’t necessarily produce true to the parent plant. But it can be a fun project to try, since they’re easy to care for. Planting root divisions is the quickest way to get gorgeous blooms in your yard.

From Seed

The seeds take a while to get going, so it’s best to start them indoors where they won’t be bothered by bugs, critters, and the weather. The beauty of this method is that no matter which growing zone you live in, you can start agapanthus seeds indoors at any time. All you need is a seed tray with separate cells, potting mix, a spray bottle, and some sand or perlite. Fill each seed cell with potting mix, spray with water, and place one or two of the flat seeds on the soil. They don’t need to be buried or poked down into the mix. Cover with a fine layer of soil and a thin layer of sand or perlite for a total cover of about 1/8 of an inch. Set the tray in a warm location out of direct sunlight, or in a greenhouse, and voila! All you have to do from now until germination is keep the seeds warm and moist (but not wet). Now, be warned that germination can take just a few weeks in warm conditions and up to three months in colder areas. So don’t let any amount of chill sneak into the area where you’ve placed your seed trays! Once they do germinate, keep the soil evenly moist, but not waterlogged. Heat Mat for Seed Germination An easy way to encourage your seeds to germinate more quickly is to place a heat mat underneath the seed tray, like this one from the Home Depot. The ideal temperature for germination is 70-80°F. When the seedlings each have three to four true leaves, you can transplant them to six or eight-inch pots filled with a mixture of organically-rich potting soil and sand. Or, use garden soil amended with well-rotted compost and sand. The key is to keep the soil loose and well-draining. Agapanthus plants grow well in pots because they actually enjoy being a bit root bound. They’ll reward you with extra blooms if you let them get nice and tight and cozy. You can leave them in the six or eight-inch pots indefinitely, or you can transplant them out to the garden or into a larger container when the leaves reach a height of six to eight inches. Go for a minimum of eight inches wide and deep for a single plant. If you started your seeds in late summer or fall, keep them in containers indoors until the following spring.

By Root Division

So where can you get a root division? First off, if you’re purchasing a bare root plant from a nursery, it came from a root division. A root division is a clone of the parent plant, so if you have a particular cultivar you would like to replicate, it’s best to divide the plant instead of saving seeds. You can plant divisions in the fall or the spring. Just note that deciduous cultivars will remain dormant throughout the winter. So if you plant them in the fall, don’t worry if you don’t see any new growth right away. You’ll need to wear gloves when you handle your agapanthus, as the sap from the leaves and rhizomes can cause skin irritation. To start, you will need to dig up the entire plant. To do this, dig six to eight inches deep around the outside of an existing clump, leaving a margin of about six inches, depending on the size of the clump. With a knife, cut the tuberous root ball in half between the shoots, so you don’t injure any new growth. Take each of these sections and cut it in two. In the end, you’ll have four new pieces, each with at least one or two shoots attached. Instead of repotting or replanting them right away, leave the new divisions outdoors, uncovered and out of direct sunlight, for 24 hours. This allows the roots to stop bleeding sap and begin healing over the cut sections. If you plant the new divisions too soon, the damp soil could get into those wounded roots and cause them to rot. Make sure the soil is loose, rich, and well-draining. It never hurts to amend the area with sand or perlite, and compost. Dig a hole that’s just deep and wide enough to fit the root ball. Set the roots inside the hole and backfill with the soil, sand, and compost mixture. Cover the entire root ball, but allow any shoots to poke up above the surface. That’s all there is to it! If you’re planting in the spring, you’ll want to give the plant one inch of water per week until it’s established. When it’s happily producing lots of leaves and flowers, you can provide just a half-inch of water a week. Agapanthus are famous for their drought tolerance and prefer not to have wet feet. But if you’re putting the division in the ground during autumn, it’s best to water it once and then let it be.

How to Grow

If you pick up a potted lily of the Nile from a nursery, or you’re ready to set out the plants you started from seed, plant them out in the fall or spring. Pick a location in full sun or part shade. Particularly in hotter areas, these plants can benefit from some afternoon shade.

Dig a hole just deep and wide enough for the root ball, and set it inside. Backfill and provide one inch of water per week, until the plant is established and you see evidence of new growth. After that, slow watering to half an inch every week. Avoid overhead watering whenever possible, and consider using drip irrigation to prevent spraying excess water on the foliage, which can lead to fungal infection. If you’re planting several of these beauties together, make sure to place them 24 inches apart, as they’ll spread up to 36 inches as they mature.

Don’t worry if they all eventually start rubbing their long, skinny elbows together. This means they’ve got a large, extra-tangly group of rhizomes supporting them from below the soil, and they love this type of closeness. These flowers can thrive in any soil pH between 5.5 and 7.5, and they don’t need much fertilizer. A dose of a 5-5-5 NPK fertilizer applied in the spring, and then again two months later, is enough to keep them happy for a whole year.

Growing Tips

Make sure plants get plenty of sun Provide organically-rich, well-draining soil Water one inch a week until established, and then slow to half an inch

Pruning and Maintenance

Knowing when and how to prune and maintain your agapanthus can keep plants healthy and vigorous, and also prevents them from becoming invasive. The most important thing to do is watch the blooming flowers closely. As the flowers start to die back, deadhead them to prevent them from going to seed. If they develop seed pods before you can catch them, it’s important to remove the entire head before the pods can open and fling seeds all over your yard and beyond.

You’ll need some gloves and a pair of pruning shears. You can then dispose of the pods in the garbage. Just be sure not to dump the flower heads anywhere that they could potentially get outside and start spreading in places where you don’t want them. Deciduous varieties will go dormant in the fall, but you’ll want to let the leaves remain on the plant until they’re completely dead and brown. This allows the leaves to continue to photosynthesize and send energy into the rhizomes for winter storage. Once all the leaves are brown and dead, gently pull or cut them off the plant. Come springtime, the plant will produce new foliage and flowers, aided by the stored energy reserves. If your agapanthus are healthy with lots of fresh foliage every spring for deciduous cultivars, or year-round for evergreens, there’s no need to divide them. But if you notice patches of yellowed, dead leaves, or if the plant is not flowering, it might mean the roots are too congested.

To fix this issue, divide the plant, according to the instructions described above. It’s recommended to divide deciduous varieties every six to eight years, and evergreen types every four to five years.

Cultivars to Select

There are a large number of agapanthus cultivars available in a variety of different colors. Here are three of my favorites.

Black Pantha

To set off your lighter agapanthus with something lovely and dark, try ‘Black Pantha’ (A. orientalis), which features black buds that open into dark violet flowers.

‘Black Pantha’ This evergreen cultivar grows best in Zones 8 to 11 and grows up to 36 inches tall. Best of all, the blooms can last up to two weeks in a vase! You can find plants available at Burpee.

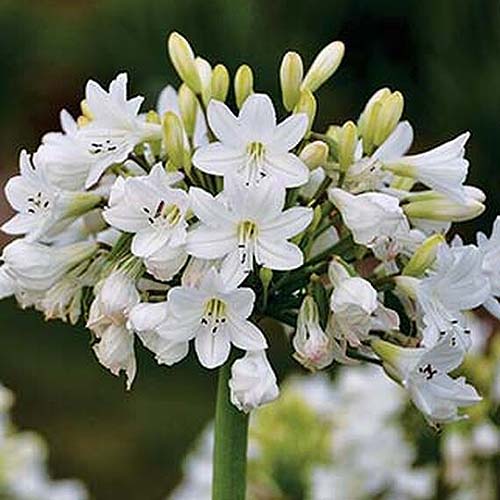

Galaxy White

Do you love your balmy clime but secretly wish snow fell at least sometimes? Fear not, because Agapanthus x. ‘Galaxy White’ is here to deliver five-inch, snow-white globes of flowers – without all the cold that comes with real snow.

‘Galaxy White’ These deciduous hybrid beauties reach heights of up to 44 inches, and thrive in Zones 6-11. Find either a bare root or a potted plant available at Burpee.

Little Galaxy

If you need a starry-eyed pick-me-up, plant deciduous Agapanthus x. ‘Little Galaxy’ in any garden from Zone 6 to 11. The light indigo flowers burst from the green stems with a joy you can’t help but share when you look at them.

‘Little Galaxy’ Reaching a height of just 24 inches, ‘Little Galaxy’ is smaller than the typical 36-inch cultivars, but its two- to three-inch globes of blossoms are the same size as those of some taller varieties. The bell-shaped flowers feature a dark blue stripe down the center of each petal for a gorgeously textured look. Find bare root plants available at Burpee.

Managing Pests and Disease

Remember when I said that agapanthus resists many afflictions, including death itself? Check out our “25 of the Best Agapanthus Varieties for Your Garden” for more cultivar selections. While those with invasive clumps may bemoan this fact, it does have an upside for gardeners who love them: they are reliably pest and disease resistant. Deer don’t trouble them, and they’re poisonous to rabbits, who will naturally give them a wide berth. The plants can sometimes fall prey to fungal diseases like powdery mildew, botrytis, or anthracnose, but if you avoid overhead watering, these usually won’t be a problem.

Monterey Liquid Copper Fungicide If you do notice the white spots of powdery mildew, the silvery coating of botrytis, or the telltale brown spots of anthracnose, remove affected leaves and spray the rest of the plant with a copper fungicide, like this one from Arbico Organics. Another issue that can develop is root rot. Are the leaves turning yellow and ceasing to grow? Root rot, caused by various species of bacteria and fungi that thrive in wet, boggy soil, might be the culprit. Resist over-watering, as plants may develop root rot as a result. By providing well-draining soil and the appropriate amount of moisture, you’ll likely avoid any issues. You can read more about identifying and treating agapanthus diseases here. As far as pests go, keep an eye out for slugs and snails. They don’t tend to kill the plant, but they do chew through the leaves and can affect its overall health.

Corry’s Slug and Snail Killer My favorite anti-slug weapon is Corry’s Slug and Snail Killer, available from the Home Depot.

Best Uses

These striking, upright flowers look lovely in a perennial flower bed, and they make a dreamy border. Mix and match different colors for an extraordinary display. The evergreen foliage provides year-round interest.

Indoors, potted agapanthus can liven up a sunny room. Wouldn’t it be divine to keep a pot of them next to a bright window in a dining room?

Quick Reference Growing Guide

The Prettiest Lily that Isn’t a Lily

I’ll never forget seeing those bright clusters of agapanthus flowers in Jamaica. One day, I’ll go back and show my son that bit of island magic.

Now you can have some of that magic in your own garden, too. Even if you don’t live in the Caribbean. Do you have any agapanthus stories, questions, or concerns to share? We’d love to hear them in the comments below. And for more inspiration for your flower garden, check out these guides next:

How to Grow and Care for Alstroemeria (Peruvian Lily) How to Grow and Care for Dreamy Delphiniums How to Grow Cleome (Spider Flower)

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Arbico Organics, Burpee, and Home Depot. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.