There was no waiting until I saw leaves with damage. No room for surprise web-covered flowers. No one else to blame if they did get out of control. Managing populations of these pinhead-sized plant suckers meant keeping close tabs on them, so every week I waded through greenhouse hydrangea plants taller than me, flipping leaves and shaking stems over my white clipboard. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. We’ve got you covered with everything you need to know! Here’s what we’ll talk about:

What Are Spider Mites?

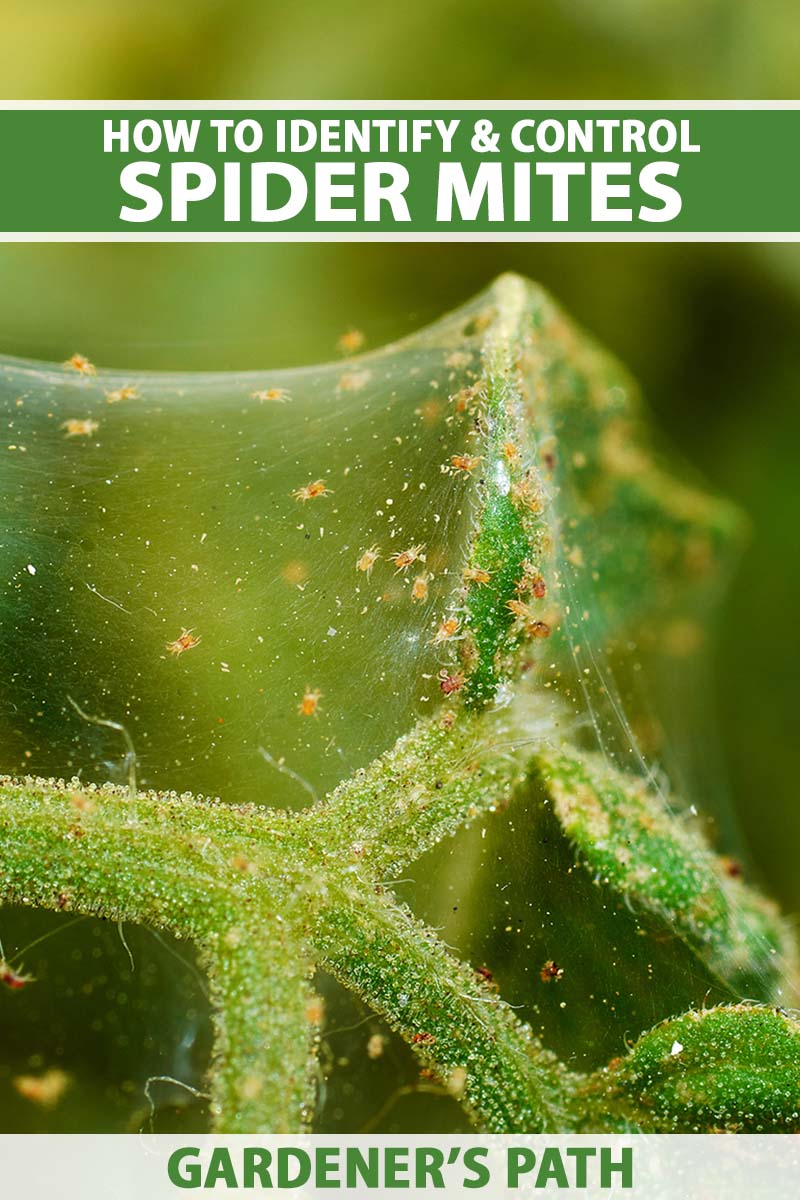

Spider mites are a common, prolific, and damaging group of pests that affect a very wide variety of flora, including coniferous trees, fruit and other deciduous trees, vines, berries, vegetables, and ornamentals. They are not insects! Think ticks, and you’re close. As arachnids, these tiny, eight-legged creatures are in an entirely different class from insects. Why are they called spider mites? Like Charlotte, they produce fine webbing, which not only protects them, but also helps these wingless creatures to disperse. We’ll talk about that more later. Belonging to the family Tetranychidae, most pest species are in the Tetranuchus and Oligonychus genera. Some are picky about their host types, while others will suck on nearly anything that’s green. With some exceptions, most species love hot, dry conditions and are especially prevalent in the summer, and in warm indoor spaces such as greenhouses. Plants that are under water stress and growing in dusty areas are very susceptible to infestation and damage. You’ll usually find these nearly microscopic arachnids feeding on the undersides of leaves, piercing the cells with their tiny needle-like mouthparts, and sucking them dry. This results in characteristic stippling damage (yellow or white dots) on the upper surface of leaves. As the damage worsens, the leaf will take on a bronze sheen, turn red or yellow, and eventually drop off. For fruit trees, leaf loss will contribute to reduced yields in the same year if the damage is done early in the summer. Unchecked feeding throughout the summer and fall can result in longer-lasting damage, lowering yields the following year. Annual vegetables will show significant yield losses if populations are large enough for premature leaf drop to occur. And on legumes such as beans and peas, feeding on pods causes direct crop loss. For perennial ornamentals such as roses, the main effects are aesthetic: stippled or bronzed leaves, leaf loss, and webbing are unsightly. Though unlikely to kill perennials, large populations can sometimes kill annual ornamentals such as marigolds and impatiens.

Identification

If the underside of a leaf looks dusty, look closer. If the dust particles are moving, it’s probably some type of Tetranychidae! In general, these arachnids are tiny, about half a millimeter to one millimeter long. To have a good look at them, use a hand lens with 10x magnification or more. They have oval bodies covered in translucent or light-colored bristles, eight legs, and two small red eye spots on their heads. Adult females are slightly larger than the males. In the immature stages prior to maturity, they look like tinier versions of the adults, though for a short period the newly hatched larvae only have six legs. The eggs, often laid individually near leaf veins and visible only under a microscope, look like miniscule water droplets. They start out spherical and clear, and turn a cream color before hatching. Certain species overwinter as mated adult females or eggs, and both will turn red-orange for the season. The different species are very hard to tell apart in the field, and a good hand lens or microscope is often needed to properly identify them. Luckily, species identification is often unnecessary, as the damage symptoms, biology, and life cycle are similar across species. It is handy to know the differences between some common species, though, especially when it comes to choosing a biological control agent, as these can be more effective predators of certain species over others. Tetranychus urticae, the globally infamous two-spotted spider mite, is the most common. It has a broad host range and will happily feed on over 200 plant species, from fruits and vegetables to ornamentals. The adults have tan bodies with two large, dark green or brown spots on either side. The spruce spider mite, Oligonychus ununguis, loves conifers and prefers the cool seasons, mainly active in the spring and fall. Adults are a dark green or brown color, fading to a lighter brown towards the head. Panonychus ulmi, the European red spider mite, is a common fruit pest. The females are red with bristles that have white bases, making it look like they have white spots. The males are very tiny, just over a quarter of a millimeter long, and have yellow tapered bodies tinged with red. Another cool weather lover, the southern red mite, Oligonychus ilicis, is mainly a pest of broad-leaved evergreens. It has a burgundy body and yellow legs. Tetranychus cinnabarinus, the carmine spider mite, has a bright red, sometimes purplish body, and loves vegetables and strawberries.

Biology and Life Cycle

The life cycle of these pests has four stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. The nymph stage also has two instars, which are known as protonymphs and deutonymphs. In optimal conditions, it only takes these pests eight days to complete the entire life cycle from egg to sexually mature adult. Adult females live for several weeks, and can lay 20 eggs per day. Laid on the underside of leaves and near veins, the eggs can hatch in as little as three days. Females do not need to mate to lay viable eggs. Unfertilized eggs produce males, which are haploid (i.e. they only have a single set of unpaired chromosomes). Females are diploid, only produced through sexual reproduction, and these have a set of chromosomes from each parent. Larvae and nymphs are also known collectively as immatures. These look like small, lighter colored versions of the adults. First, the six-legged instar known as the larva emerges. From there, the protonymph and deutonymph immatures have eight legs like the adults. These aptly named arachnids produce fine silk webbing, which protects the colony from rain, wind, and predators, and is useful for dispersion. Tetranychidae species are very mobile, but once they find a good spot to feed, mate, and lay eggs, such as in your plant collection, they settle into the sedentary phase and multiply to form large colonies. If the host plant becomes too unhealthy and food is scarce, they aggregate and enter a dispersal phase. At this point they either walk to a new location on the plant, walk to another plant, or position themselves on the top of a plant to catch the next breeze out of town. If they are very overcrowded, those in the immature stages often use their web-spinning abilities to disperse. Aggregating into a ball of individuals and silk at the top of a plant, they wait for a gust of wind or a passing animal to carry them elsewhere. This action is known as ballooning. In warm climates and greenhouses, you can find them feeding and reproducing year round. In cooler climates, they will either overwinter as red- or orange-colored mated females under bark or in debris, or as eggs, which also often take on a red hue at this time of year.

Monitoring

If you have good eyesight, you may be able to see individual spider mites on the leaves as you tend your plants. But since they are so tiny and love to live on the undersides of leaves, you will likely need to put in some effort to catch them before they begin causing serious damage. Noticing them before populations explode will make your life as a gardener much easier, because once they’ve infested a plant, it can be difficult to achieve (or regain) complete control. Regularly flip a few leaves over and use a hand lens to scan the underside for eggs, immatures, or adults. Keep an eye out for webbing on the undersides as well as on flowers, and spanning from leaf to leaf. And of course, be on the lookout for white or yellow stippling on the upper surfaces of the leaves. To help determine if you are dealing with these pests, shake or tap leaves that bear stippling damage over a sheet of white paper. Any insects on the leaves that land on the paper will be more easy to identify.

Organic Control Methods

Because these eight-legged suckers prefer leaf undersides and stressed plants, produce protective webbing, and are highly mobile, controlling them can be tricky. However, there are a variety of control options available to add to your toolbelt. Approach a spider mite problem with an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy, which combines good monitoring, plant health improvements, and removal strategies with the use of beneficials and safe chemicals for optimal and long-lasting control. You can find out more about IPM and how to design a good program here. It can be hard to tell the difference between the two types as they crawl around, even with a hand lens. If you are tapping your plants over white paper as a monitoring technique, you can use the smear method to easily tell if those landing on your page are beneficials or pests. Some will enter from nature and provide control, but assassin bugs and lacewing larvae are also available for purchase at Arbico Organics, and can be applied on infested plants. One of the best ways to control these pests is with predatory mites. A large variety of beneficial species from the Phytoseilus and Amblyseius genera serve as effective predators, and are often used by growers. Amblyseius swirskii is popular with greenhouse growers. It loves warm climates and preys on several spider mite species, as well as whiteflies and thrips. Amblyseius swirskii A variety of application types, including slow-release sachets for preventive control, are available for purchase at Arbico Organics. A. andersoni can survive in lower temperatures than A. swirskii and will attack other pest species, such as broad and russet mites, as well. Find these beneficial arachnids at Arbico Organics. Phytoseiulus persimilis is often the predator of choice for treating large concentrations of mites in humid greenhouses. Since they especially love T. urticae, they are commonly used by commercial growers. Phytoseiulus persimilis Visit Arbico Organics to find live mites for purchase. Galendromus occidentalis, aka the Western predatory mite, is a good predator to use on fruit trees. Galendromus occidentalis It does well in hot and dry conditions, and is available for purchase at Arbico Organics. So how do you tell the difference between pest and predatory mites on your plants when you are scouting? Most predatory species have longer legs, are quick and more active than the pests that feed on plants, and are teardrop shaped. Squish and smear the mites on the page with your finger. In general, if the resulting streak is green, it’s a pest. If it’s red, it’s predatory.

Cultural and Physical Control

A lot of the cultural and physical control options available to the home gardener to deal with these pests involve water. Many predatory species can’t move around well on hairy plant leaves, but these predators are agile and work well on a variety of crops, especially vegetables. Feltiella acarisuga They prefer high humidity, so they are a great choice for eradicating pests in greenhouses and on densely grown crops, or plants with highly compacted foliage and limited airflow. Purchase these at Arbico Organics. You can also combine Feltiella acarisuga applications with P. persimilis for effective control of heavy infestations. The spider mite destroyer beetle (Stethorus punctillum), a shiny black insect in the ladybug family, is a very efficient predator as well. Both adults and larvae will feed on spider mites, and can eat up to 40 per day! Spider Mite Destroyer Beetle (Stethorus punctillum) They are experts at finding infestations, and will fly throughout the greenhouse or garden to locate a meal. Purchase these voracious beetles at Arbico Organics. Plants under water stress are targeted by spider mites, so keep your plants hydrated and healthy. They also tend to attack dusty plants more often than ones with clean foliage, so if you live in a dusty area or have plants growing near a dry road or path, hose them down occasionally to keep them clean. Spraying plants with a hard jet of water can help to remove spider mites and their webs from leaves. Make sure you wash or spray your plants in the morning so they can dry off quickly, to prevent disease. Since biological controls are not an option on houseplants, the available level of control indoors is limited. Move infested indoor plants away from healthy ones, preferably into a cooler room or area. Keep the leaves clean by wiping them down with a damp cloth or by giving plants a cool shower. Remove and destroy any extremely infested plants to reduce the chance of spread.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Broad spectrum chemical applications, especially if applied when the weather is hot, can actually contribute to spider mite outbreaks. Bonide Insecticidal Soap Apply an insecticidal soap, such as this one from Bonide that’s available at Arbico Organics, or Garden Safe Insecticidal Soap, which you can find at Home Depot, to decrease pest populations before introducing predatory species. Garden Safe Insecticidal Soap Allow these products to at least dry on the plant before applying beneficials. Monterey Horticultural Oil Horticultural oils such as this one from Monterey, available from Arbico Organics, or neem oils, including this one from Bonide, also from Arbico Organics, can also be effective in knocking down populations, provided you get good coverage. Bonide Neem Oil To treat for overwintered eggs, use a dormant oil spray such as Bonide All Seasons Horticultural and Dormant Spray Oil, which you can also find at Arbico Organics. Bonide All Seasons Horticultural and Dormant Spray Oil Make sure you aren’t applying sprays and oils on water stressed plants or when it’s hotter than 90°F, as this can burn the plant. You may see some temporary relief, but since broad spectrum chemicals kill beneficial insects as well, the predator-free environment gives spider mites the opportunity to multiply into populations so large that any returning or reapplied biologicals can’t keep up. Plus, some chemicals such as carbaryl seem to stimulate pest mite reproduction. In general, applying chemical pesticides isn’t helpful for ongoing control. Use a combination of organic pesticides, cultural methods, and biological predators as described above to achieve effective control over these pests. Regular, detailed scouting trips and preventative applications of beneficial insects are what saved me from the stress of dealing with a complete spider mite takeover at the nursery. What would your control strategy be if you spotted a spider mite colony on your plants? If you’ve ever dealt with an infestation, I’d love to hear about it in the comments below! And for more information on battling pests in your garden, check out these guides next:

Managing the Aphid: An Unwelcome Garden VisitorHow to Manage a Spotted Lanternfly InfestationHow to Identify and Control Mealybugs