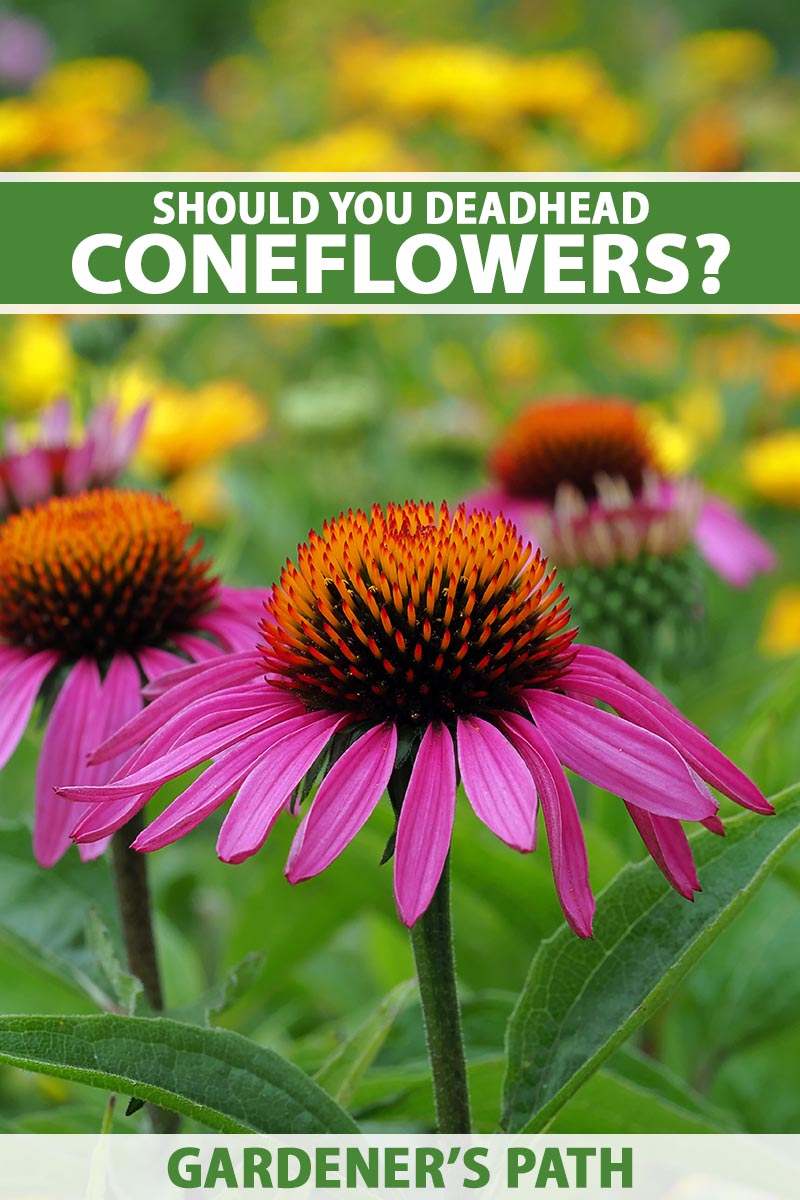

There are nine species and numerous cultivars for an array of color, height, and style options. Perhaps best known is the purple coneflower, Echinacea purpurea. The blossoms have protruding center disks that attract beneficial pollinators galore throughout the growing season, and foraging songbirds like goldfinches feast on the seeds at season’s end. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Our roundup of 17 fabulous coneflower varieties provides a list of exceptional options from which to choose. In this article, we focus on deadheading. First, we’ll define the practice, and then weigh the pros and cons, so you can make an informed decision when caring for your coneflowers. Here’s the lineup: Let’s get started.

What Is Deadheading?

A flower sets seed after blooming, unless it is severed from the plant before it gets the chance. The process of cutting off individual spent blossoms, as well as stems containing multiple blossoms that have finished blooming, is called deadheading. Stems are cut just above a leaf node, or at the base where they originate. Energy is redirected from reproductive to vegetative growth, resulting in lateral growth, and ultimately more buds and blossoms. In addition, some folks snip off the growing tips of stems earlier in the growing season, sacrificing a potentially large bloom, to promote lateral growth for a bushier plant with more flowers. And in the warmest zones, plants in a summer lull are often not just deadheaded, but cut back by up to one-half of their height, for a late season flush of growth. This is not advised in cooler regions, as there may not be time for reblooming before the first frost.

The Nature of Coneflowers

Coneflowers have a basal mound of foliage from which upright stems sprout. Each stem has a terminal bud that blooms for a few weeks. After blooming, lateral growth may produce more buds. Here in Southeastern Pennsylvania, the first flush of echinacea arrives in late spring to early summer. And while species like the purple, E. purpurea, and yellow, E. paradoxa, are called continuous bloomers, they tend to be the most vigorous early in the season, before summer heats up. This year, we’ve had a cool, wet spring interspersed with some hot, dry days. My neighbor’s tall purple echinacea are out in full and glorious splendor in partial shade, while my more compact red ones are basking in the sun, still in the bud stage. I tell you this to illustrate that plant performance varies widely and is affected not only by type, but also by conditions like exposure, moisture, nutrients, and soil quality.

On the Pro Side

Even a supposedly continuous bloomer may benefit from deadheading. The cutting of spent stems and redirection of energy into more blossom production can help to bridge the natural gaps created by lulls in blooming that occur naturally throughout the growing season. It also helps to keep plants neat, contributing positively to a garden scheme, not only because you are removing debris, but because you are inhibiting the random self-sowing of seeds. In addition, the removal of decaying foliage reduces vulnerability to pests and pathogens, and supports overall health and longevity. And finally, in the warmest regions, you have the option of the mid-season cutback for a vibrant late season show.

And the Cons

From a bird lover’s standpoint, a drawback of removing flowers instead of letting them set seed is that forging avian species will be deprived of a late season food source. Also, buds that form on the lateral stems generated by deadheading may open into blossoms that are less showy than those of the upright main stems. And if you’re a seed saver, deadheading will deprive you of the ability to save and share seeds from your favorite varieties. On the pro side, we have:

Promoting more blooming to offset lulls during the growing season.Keeping plants neat.Minimizing self-sowing.Reducing vulnerability to pests and disease for overall good health.And, in the warmest zones, the option to dodge midsummer heat altogether with a cutback for a last hurrah.

And on the con side:

Supplying few to no seeds for foraging birds.Stimulating the growth of more, but potentially smaller blossoms.Enabling the collection of seeds to save and share.

And while some types have a natural tendency to rebloom, like the purple, E. purpurea and yellow E. paradoxa, deadheading can only serve to support this behavior, especially as summer heats up and plant growth slows down. What clinches the decision for me is this: The longer I can keep a plant from running to seed, the longer it will bloom and add color to my landscape. I like to deadhead the echinacea in the front of my house, and leave the ones in the back to set seed. That’s where I let things get a little wild and wooly with native plants, a birdfeeder, and a birdbath. I also have outdoor seating so the family can enjoy nature’s show. The red variety that I mentioned is in the front garden, where things are more manicured. That’s the one I deadhead regularly. I like the neatness, and the idea of squeezing out as many blooms as I can, regardless of size, for showy curb appeal. It’s your turn. Will you deadhead some, all, or none of your coneflowers this year? Please tell us your thoughts in the comments section below. If you enjoyed reading about the pros and cons of deadheading garden flowers, you may like to read these articles next:

Do I Need to Cut Back Bicolor Iris?Do Fuchsias Need Deadheading?