Unfortunately, like most plants, they are susceptible to a number of diseases. And it’s important to note that certain species may be more readily affected than others. Even those who haven’t grown their own chestnuts before are probably familiar with the notorious blight that wiped out the American species across the US – though you may not have heard of another serious widespread epidemic that severely impacted the same species centuries before. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Here’s what’s ahead:

1. Anthracnose

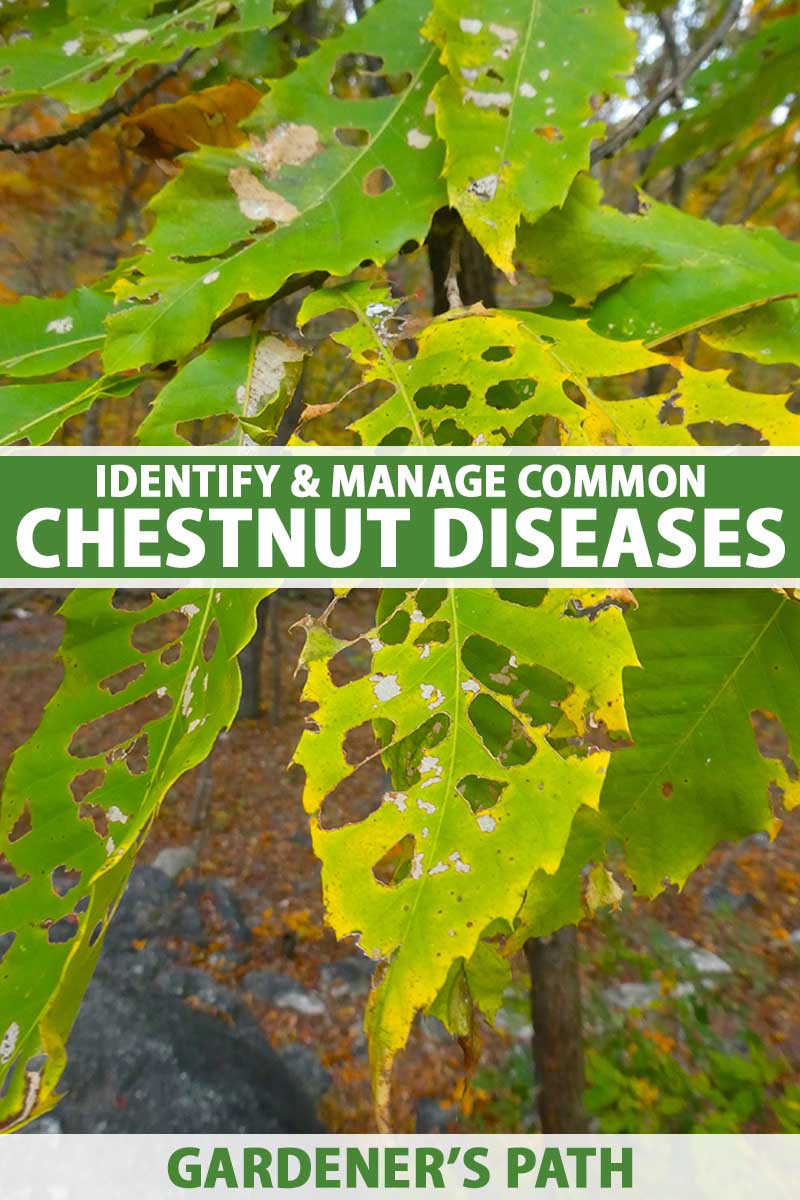

A common disease in oak trees and other varieties of deciduous hardwoods, chestnuts may be affected by anthracnose as well. Symptoms of infection include dry, brown, irregular spots on leaves, curling foliage, and defoliation. Twig dieback may also occur, and buds may die early in the season, exhibiting symptoms that resemble frost damage. Small pimple-like fungal structures may be visible on the undersides of affected foliage as well, if you want to get out your magnifying glass. Caused by Apiognomonia quercina fungi, the spores may be spread by the wind and splashing water in the spring, infecting new growth. Infections are usually the most severe on the lower and innermost branches. Prolonged periods of wet weather are favorable to the spread of this disease, and of course, wet weather is common in many regions in the springtime. But the most important factor is actually temperature. Anthracnose tends to be the most severe when temperatures are in the 50 to 55°F range, and less severe in temperatures of 60°F and above. New leaves may grow back later in the season, while seriously affected trees may not recover, particularly if a springtime infection is followed by a period of drought or other stressors. This fungus can overwinter in cankers on the branches, and in fallen leaves. Be sure to complete a thorough cleanup of the garden to remove all affected plant matter that has fallen, and prune away and burn or otherwise dispose of any dead branches and twigs to prevent further spread. Fungicides may be applied at bud break, but this is not typically recommended for home gardeners.

2. Chestnut Blight

The American species (Castanea dentata) is highly susceptible to chestnut blight, and European chestnuts (C. sativa) and their hybrids are susceptible as well, though importing these trees to the US is rare these days. Some varieties of oak are also susceptible to infection. There is unfortunately no available treatment for chestnut blight, a fungal disease caused by Cryphonectria parasitica. It enters the trees through wounds, often those made by insects, and the infection develops under the bark. This disease was responsible for wiping out American chestnuts across the US in the first half of the 20th century. Infected trees exhibit cankers, which may sometimes be confused for evidence of sunscald. Also known as chestnut bark disease, infected branches become girdled with cankers and die off quickly. Affected limbs should be removed and destroyed, to prevent further spread. Dead leaves will cling to infected trees rather than falling in autumn, and yellowish-brown fungal fruiting bodies may be visible around cankers and cracks in the bark. Cankers are more apparent on younger trees, whereas they may remain hidden under the bark for some time in mature specimens. Though trees killed by this disease will sometimes send out suckers with apparently healthy growth if the roots survive, these will eventually succumb as well. The fungus can overwinter in the bark, and the spores can become airborne, spreading easily to new areas. More prevalent in the eastern part of the country historically, growers out west once planted European chestnuts without much concern, though this disease is considered widespread throughout the US today. Choosing blight-resistant varieties is recommended for home growers. Chinese chestnuts (C. mollissima) as well as Chinese-American hybrids show good resistance, and Japanese varieties (C. crenata) show some resistance as well. Be sure to purchase trees from reputable growers that are certified free of disease.

3. Nut Rot

Reportedly caused by several different species of fungi including Sclerotinia pseudotuberosa, Phomopsis castanea, Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi, and Diaporthe castaneti, nut rot infections are most notable in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. A disease of harvested nuts rather than the trees themselves, rot can cause significant crop losses. While the unshelled nuts may appear healthy, the kernels inside have a different story to tell, appearing discolored, spotted, or speckled, and soft, moldy, or rotten. In the case of severe infection, shells may show signs of mold and rot as well. Exhibiting similar symptoms but not caused by a pathogen, when European-Japanese hybrids are pollinated by Chinese species, they may exhibit internal kernel breakdown, a physiological disorder that causes nuts to decay. Harvesting frequently is important, to prevent the onset of nut rot, and cold storage of harvested nuts can help to prevent or delay onset. The fungal spores can survive in nut husks (also referred to as burrs) for several years, so care should be taken to remove unharvested nuts and discarded burrs from the orchard or garden to prevent further spread. Dispose of burrs that are infected with fungi in the trash, or burn them if this is permitted in your area. Do not put plant matter that contains disease pathogens on the compost pile.

4. Phytophthora Root Rot

Also referred to as ink disease, root rot is caused by Phytophthora water molds. Particularly prevalent in trees planted in soil that does not drain well, with onset typically occurring in early spring, the disease pathogens can also be carried on plants purchased from nurseries. P. cinnamomi can cause rot infections in chestnuts throughout the US. This species was introduced on plants brought by colonists from Europe in the 1700s, and is thought to have eradicated American chestnuts from low-elevation forests in the southeast long before the introduction of chestnut blight. Since that time, its range has expanded. P. cambivora infections of European chestnuts and other types of hardwood trees are prevalent throughout Europe. P. cambivora may also cause rot infections in American and Japanese chestnuts, and has been noted as the cause of rot disease in the US and Asia. Though the infection is centered at the roots and the base of trees, infected chestnuts will show signs of wilt and branches will die back. Trees can succumb quickly, and often die. Peeling back the bark of an infected tree would reveal black or brown necrotic tissue. Growers refer to this as the “flame” because it appears as if their trees have been scorched. Since the oomycetes can remain in the soil for several years, do not replant chestnuts in the same location if one succumbs to root rot. Chinese chestnuts are resistant to this pathogen, but not immune.

5. Sudden Oak Death

Another devastating disease caused by Phytophthora water molds, sudden oak death affects oaks and their relatives, as well as a variety of other types of trees and understory plants including rhododendrons and camellias. A then-unidentified infection was reported to be plaguing trees in Marin County, California in 1995, and deadly sudden oak death infections were first noted and identified in the forests of Oregon in 2001. Since then, infected nursery stock has been found in at least 25 states in the US. Also known as Ramorum disease. P. ramorum favors wet conditions. Temperatures above 80 or below 59°F slow its growth, but springtime temperatures in the upper 60s usually hit right there in this fungus-like organism’s sweet spot. Cankers on the bark of infected trees often ooze with a black or reddish liquid, leaves exhibit spotting, and twigs die back. If you suspect that your trees are infected, contact your local agricultural extension specialist. This disease can often be confused for ailments caused by other pathogens. The water molds can be spread via infected soil, and wind-blown or splashing rain. Do not replant susceptible trees or shrubs in the same place where another plant has succumbed to this disease. Chestnuts are under quarantine by the USDA to prevent further spread of this pathogen, and deliveries of seedlings and saplings from nurseries outside your state may not be available in certain areas. Be sure to follow any quarantine regulations that are active in your region to prevent potential spread. Ensure that they are planted in soil with good drainage, and prune to improve airflow and allow sunlight to penetrate the canopy. If you’re planting chestnuts for the first time, or acquiring more to add to your orchard, look for disease-resistant varieties, and give your business to nurseries that ensure disease-free seed stock and saplings. The spread of many pathogens is particularly common when conditions are rainy and cool in the spring, and you can sometimes nip an infection in the bud via pruning or thorough garden cleanup at the end of the season. It’s sad but true that the American chestnut has been wiped out more than once in the US thanks to disease, though horticulturists are making efforts to save this noble tree, and development efforts are underway to produce new hybrids and cultivars that produce tasty harvests while resisting disease. Thanks in large part to these efforts, you can grow your own chestnuts at home today! Have you encountered disease in your orchard? Do you have any stories or questions to share? We love hearing from you! Please post your messages and share photos in the comments below. And for more information about growing your own nut trees at home, read these guides next:

How to Grow and Care for ChestnutsHow to Identify and Manage Common Chestnut Tree PestsHow and When to Prune Almond Trees