I first learned about Charlotte in another book I reviewed, The Humane Gardener, by Nancy Lawson.

An Almanac of Alternatives

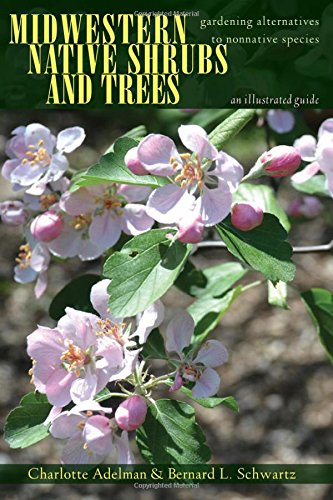

Meticulously researched, and annotated, this in-depth guide synthesizes a vast body of knowledge on subjects ranging from native and nonnative woody plants to biodiversity, lepidopterology (study of butterflies and moths), and ornithology (study of birds), with references to works by renowned experts such as University of Delaware Professor of Entomology (study of insects) Douglas Tallamy. Midwestern Native Shrubs and Trees: Gardening Alternatives to Nonnative Species It’s a comprehensive and ambitious undertaking that focuses on substituting native woody plants for nonnatives in Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Ontario, Canada. However, the material is also applicable to states bordering this region, and to the Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province (EBF) region. Per the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, this includes portions of all of the states listed above except Kansas, plus areas of New York and Tennessee. Native, nonnative, and invasive designations are sourced from the USDA. The book itself is a glossy paperback with 430 pages of text that measures 6 x 1.1 x 9 inches. Photos and illustrations depict woody nonnatives, and alternatives that promote biodiversity and enrich habitat for wildlife.

Partners on the Prairie

As a resident of Pennsylvania, a state bordering the Midwest region, I delved eagerly into pages loaded with beautiful photos of familiar trees and shrubs. The Midwestern Native Garden: Native Alternatives to Nonnative Flowers and Plants, an Illustrated Guide This first work introduces readers to the notion of phasing out nonnative ornamental plants and replacing them with indigenous varieties, to contribute to the restoration of biodiverse ecosystems in the Midwest. My first impressions were that this is a scholarly publication with detailed descriptions, abundant illustrations, and a unique color-coded plant identification system. Happy with what I had seen so far, I wanted to learn something about the authors of this impressive volume. The book jacket contains a modest blurb about the two authors, citing two previous books, the 2012 Helen Hull Award from the National Garden Clubs, and an Audubon Chicago Region Habitat Project Conservation Leadership Award. But their list of accomplishments doesn’t end here. Charlotte and her husband Bernard are a dynamic couple who retired early from professional life as attorneys to actively pursue grassroots conservation projects in their region. Beginning with one small lot, they acquired a Midwestern property, instituted a Kettle Moraine Land Trust (KMLT) conservation easement on it, and turned the land over to The Prairie Enthusiasts. The volunteers of both organizations work together to maintain the Adelman & Schwartz Preserve. Charlotte has also made a positive environmental impact by preserving dead trees called “snags,” whose cavities provide shelter for wildlife. She has been recognized by The Cavity Conservation Initiative for her efforts.

A Seasonal and Systematic Approach

Having formed a positive overall impression, I curled up with a cup of tea and began an enjoyable and informative read. From the detailed and well-documented preface, I learned the authors’ straightforward mission: To teach Midwesterners that planting locally adapted plants attracts the wildlife that co-evolved with the plants, creating an ecologically diverse and environmentally beneficial natural landscape. And, to provide the tools necessary to distinguish undesirable nonnatives from more desirable indigenously derived woody plants. I proceeded to a section which explained how to use this encyclopedic text, and discovered an ingenious and user-friendly system.

Season by Season

The book is divided into four chapters: Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter. Each is amply illustrated, and the fall and winter sections have additional photo “galleries” that showcase even more indigenous plants.

As I sipped my tea, I began to read the first chapter, “Spring.” Two charming pages encouraged me to consider thinking outside the suburban box, and recalled a bucolic time in the Midwest, with an abundance of unspoiled native flora and fauna. Within each chapter is a list of nonnatives that are prevalent in residential gardens, and whose most dramatic characteristics feature prominently in that season. So, for example, you’ll find nonnative scarlet firethorn in the Fall section, because that’s when its bright berries appear. You may also use the comprehensive index at the end of the book to look up any Midwestern tree or shrub, nonnative or native, alphabetically.

Color-Coded System

Common nonnative trees and shrubs are listed alphabetically in red print. Pertinent plant facts are listed, such as Latin name, how to cultivate, dimensions, wildlife attracted, and hardiness zone. Following each nonnative listing are native alternatives printed in green. These are the ones you want to grow to benefit the environment, create habitat, and inhibit the proliferation of invasive species. That means, for example, that if you look up “golden rain tree” in the index, you can see at a glance – by its red print – that it is a nonnative species. The full listing is in the Summer section, because that’s when it puts on its golden blossoms. Here you’ll learn that this plant is from China and Korea, with little to offer local wildlife, compared to the locally adapted indigenous alternatives listed in green. These include the American linden and honey locust, which attract regional birds, bees, and butterflies, contributing to the biodiversity the authors aim to restore. Folks, it just doesn’t get any easier than this.

Abundant Resources

In addition to shrubs and trees, you’ll find woody vines and ground covers, like nonnative and native varieties of honeysuckle and climbing hydrangea. Chapter and section headings at the bottom of most pages further aid in locating desired material. You’ll find a lengthy list of notes at the end of the book explaining the numerous references to scholarly works cited throughout the text, as well as a useful glossary of terms. There are also a useful bibliography and resource list to consult for additional research. The final source is an intriguing list based on University of Delaware professor Douglas Tallamy’s study of the number of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) that native trees, shrubs, vines, and herbaceous plants host. Would you believe that native oaks can sustain 534 species? The pictures in this elaborate volume are stunning. Many photos were taken by author Bernard L. Schwartz. A complete list of photos and illustrations of wildlife and plants appears at the end of the book, and provides common names as well as Latin.

Gardener to Gardener

I had the privilege of corresponding with Charlotte for elaboration on some key points she makes in her book. She stressed the importance of making a positive difference, no matter how small or large one’s property. “Each tiny back, side, or front yard – or even container garden – holding native plant species can serve as a “stepping stone” which connects isolated islands of habitat to each other” Charlotte stated. She went on to say that when we plant even one native tree or shrub, we create another link in the “wildlife corridors” traveled by migratory birds. Charlotte is passionate about the relationship between native plant and animal species, and described the joy of witnessing it firsthand: “Most people think bees can get nectar and pollen from any old plant, native or nonnative… many bee species and the native plant species with which they evolved are co-dependent… native plant species that co-evolved with the specialist bees help both the bee species and the plant species survive. “An example is the American/tall bellflower (a self-seeding biennial), which attracts (and supports) an oligolectic (specialist) bee. When the sun shines on these shade-loving flowers, nothing gives me more pleasure than standing in front of a patch of my long blooming, beautiful, blue American bellflowers and watching the oblivious-to-me tiny specialist bees gathering nectar and pollen.” Gardening with native plants affords exciting opportunities to witness the intricacies of an ecosystem at work. When the sun shines on these shade-loving flowers, nothing gives me more pleasure than standing in front of a patch of my long blooming, beautiful, blue American bellflowers and watching the oblivious-to-me tiny specialist bees gathering nectar and pollen. I asked Charlotte about an insect’s ability to adapt to the ornamental nonnative plants that adorn many a home garden. This is not something we can expect to see in our lifetimes. Here’s her explanation: ”A big reason for the slowness of insect adaptation to nonnatives is because the native plants in North America and the plants in Asia and Europe evolved to have different leaf chemistries. Just as different leaf chemistry is why most North American insects cannot eat nonnative plants, different (or changed) leaf chemistry is also the reason why certain native insects cannot eat certain nativars. “Rather than expect people to keep up on which nativars are known to harm native wildlife because of features like no berries, no seeds, inaccessible nectar and/or pollen, unacceptable flower colors, indigestible leaf chemistries, and other wildlife unfriendly characteristics, the message should be: Eliminate the guesswork, plant the species that are well known to help local wildlife, and choose regional native species.” I told Charlotte that butterfly bushes are popular in my area, and available at every garden center. Sadly, they do not support the entire life cycle of butterflies. While they provide food for adults, they do not nourish young caterpillars. Native plants are ideal because they support a whole life cycle. Look for butterfly shrub instead; it’s in her book.

One Plant at a Time

Throughout this expansive volume, Charlotte and her husband, Bernard, make a solid case for the benefits of choosing natives over nonnatives. In addition to benefitting the birds, bees, butterflies, and other insects that thrive on them, natives are easier to grow and maintain than their purely ornamental nonnative counterparts. As advocates for native planting to sustain wildlife, the authors are fulfilling a personal goal. By sharing the information they use to guide them, they enable fellow Midwesterners to join them in making a difference, one plant at a time. I recommend Midwestern Native Shrubs and Trees as a practical handbook for all gardeners in the heartland and adjacent states. Use it to identify the nonnative shrubs and trees on your property, and to choose native alternatives to restore vital habitat before it’s too late. If you’re interested in further reading on native plants, consult our articles on vines for your landscape and blue wildflowers. This seminal work sheds light on the demise of grasslands in the wake of progress, and guides travelers to remnants of prairie that echo nature’s once pristine landscape. Prairie Directory of North America: The United States, Canada, and Mexico It’s time to take a hard look at your garden and decide if your landscaping sustains native pollinators like bees, birds, and butterflies. Remember, even one indigenous plant creates a “stepping stone” in the network of wildlife corridors essential to native species. Will you plant a native tree or shrub today? Tell us about your efforts to preserve fragile ecosystems in the comments section below. Happy reading! And for more gardening book reviews, check out some of these selections:

Teaming with Microbes: A Fresh Review for Today’s Gardeners Exploring Rodale’s Ultimate Encyclopedia of Organic Gardening Celebrating 40 Years: A Review of The Encyclopedia of Country Living

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Photos in this article are owned and copyrighted by their respective owners as identified. Reprinted with permission by Ask the Experts, LLC. All rights reserved by all parties.