Or maybe they’re only palatable at certain times of the year? But you’ve also heard that maybe some species are toxic? Or was it just if you ate too many berries? Yep, it can be confusing. Most people know those little blue wonders as a flavoring for gin, and some adventurous eaters may have even used them as a seasoning for meat. Obviously, some juniper berries are edible or we wouldn’t have gin. We also wouldn’t see them dried and sold in spice jars at the grocery store. But not at all species are palatable, and some are quite poisonous. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. Here’s what you can expect in this article: These tangy little treats are absolutely fabulous in a massive range of recipes, so if you’re ready to get cooking, read on!

A Brief Introduction

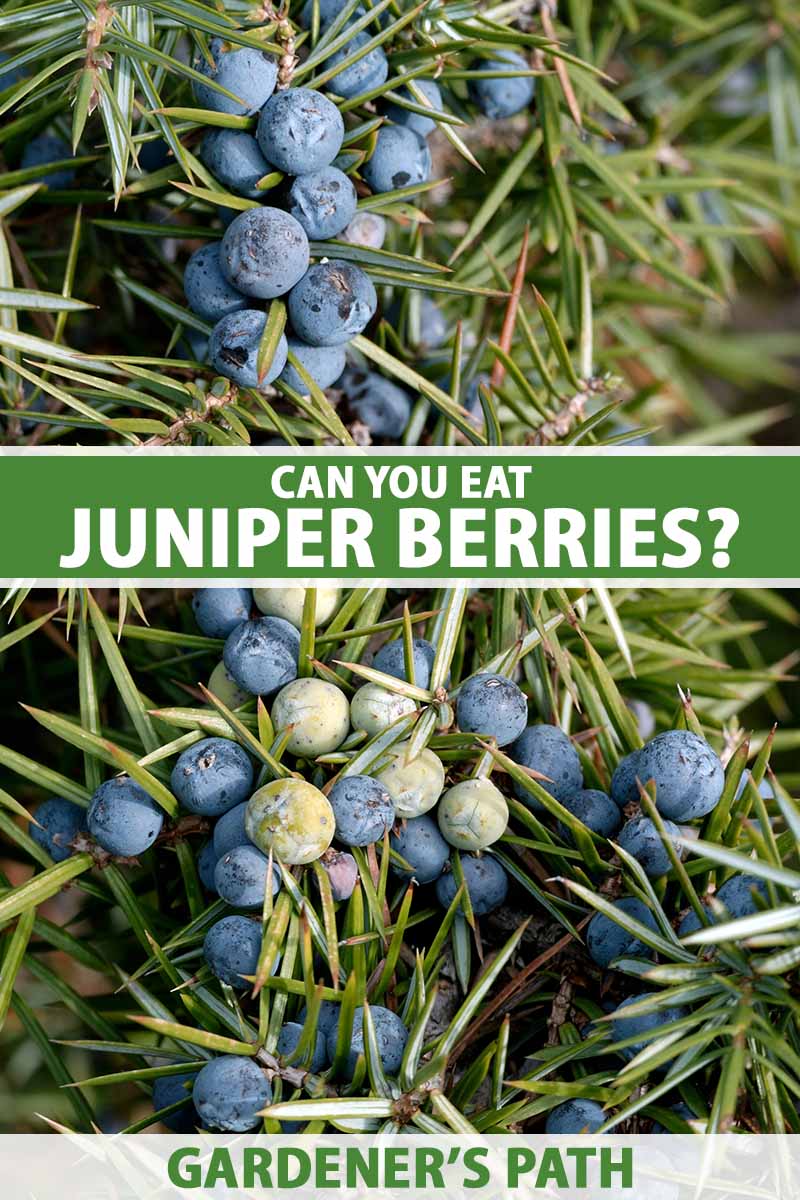

First of all, let’s set the record straight. Juniper berries aren’t berries at all. They’re modified cones. I know, bonkers, right? Instead of having scales like the cones most of us are familiar with on conifers, they have such small scales that this ends up looking like a thick, almost leathery skin. Despite the misnomer, we’ll keep calling them berries because that’s how they’re best known. Each one of the fruits contains several seeds, usually six, but sometimes as few as one seed per berry. These are far more commonly used in cuisine in Scandinavian countries, other parts of Northern Europe, and Russia than in the United States. Here, they don’t receive much attention beyond that from gin lovers. They regularly appear as an ingredient in cookbooks and in foraging guides in Europe, but juniper doesn’t appear too often in North American cookbooks. And they don’t even receive a mention in Samuel Thayer’s works. Thayer has written what many regard as the definitive guides to foraging in the US, but no love for our Juniperus friends! That said, many Native American people know the value of these marvelous plants, and most gin in the US is made with juniper cones (though it’s the underripe green ones that are used to make gin). In Europe, beyond being used for gin-making and as a seasoning for meat, the fruits are sometimes used as a substitute for pepper. The unique flavor of the cones is sharp, resinous, woody, and somewhat floral. Some species can be a bit sweeter, and others are downright bitter – each berry can be comprised of up to 33 percent sugar. The flavor comes primarily from terpenes, aromatic compounds that are found in many types of plants. Juniperus communis is the species most often used for flavoring gin and for eating, but it isn’t the only species that is edible. Dozens of species have been used by Native Americans, including the American (J. californica), creeping (J. horizontalis), one-seed (J. monosperma), Pinchot’s (J. pinchotti), Rocky Mountain (J. scopulorum), Sierra (J. occidentalis), Utah (J. osteosperma), and Virginia (J. virginiana) junipers. However, J. communis is most commonly utilized by native people in North America, with J. scopulorum coming close behind it. In addition to culinary applications, these berries have a history of medicinal use as well. The Algonquin, Inupiat, and some Tanana tribes use various species to treat colds, while Blackfoot people use it as a way to treat certain sexually transmitted infections and lung diseases. Some Cree people smoke the berries as a treatment for asthma, and the Hanaksiala make a poultice with the fruits as a paste to treat wounds. It has also been used for contraception and urinary tract infections by various native people.

Juniper Identification

So, if you’re ready to start eating these underappreciated wonders, how do you go about finding the ones that are safe to eat? If you’re allergic or sensitive to any of the compounds, they can also cause dermatitis or blisters when handling the fruits.

First, let’s start with identifying true junipers by differentiating them from other conifer species. By the way, if you want a bit more info on how to tell conifers of various types apart, we have a helpful guide for that. There are about 60 species in the Juniperus genus that grow wild in the Northern Hemisphere. These are all trees or shrubs that can grow up to 40 feet tall, and all are evergreen. They all inhabit dry, rocky areas and regions with periods of extreme heat and cold. If you’re foraging in a shaded, moist, temperate area, you’re not likely to find this desert-lover. Cypress trees (Cupressus spp.) are often confused with junipers, but cypress cones are larger, with angular edges. They might have a pointed tip as well. They also, of course, lack the characteristic juniper scent – and they are considered toxic. If you see an evergreen with red fruits, steer clear! It’s probably a yew tree (Taxus spp.), and those fruits can kill you if you eat the seed inside that bright red aril. Incidentally, the fleshy aril is edible, but it’s best to proceed with caution when dealing with this plant. The cones on Juniperus species emerge from the leaf axils, which are the joints between the leaf and the stem. If you see fruits growing from a different point on the plant, what you’re looking at is not a juniper. Speaking of, the distinct scent is another dead giveaway. Nothing smells quite like juniper. Once you find one and inhale the scent, you’ll probably have no trouble distinguishing it in the future. Here are the most common edible species: Virginia juniper (J. virginia) is the most common species across the eastern US. This species is sometimes called Eastern red cedar – which is confusing, since it isn’t a cedar. The fruits are pale blue and about three millimeters in diameter, and the leaves are scale-like and either finely cut or coarse. J. communis has thick, stiff, scalelike leaves in whorls of three. The fruits of this species are silvery blue when mature, and grow to about six millimeters in diameter. The Rocky Mountain species (J. scopulorum) grows in, you guessed it, the Rockies. It has scalelike leaves in pairs that appear opposite each other on the branches. The foliage is fine and soft, and the silvery-blue berries are six millimeters in diameter. Utah juniper (J. osteosperma) has scalelike leaves in opposite whorls of three, and it grows in the southwestern US. The cones are blue-brown and quite large. They can top out at 13 millimeters in diameter and ripen in just 18 months – much quicker than what you’ll typically see in other species. Western juniper (J. occidentalis) has reddish bark that peels away from the twisting trunk. It has scale-like leaves in whorls of three. The cones have one to three seeds each, and are deep blue with a whitish coating when ripe, which happens in the second year of growth. They range between five and 10 millimeters in diameter. Southern redcedar (J. silicicola) isn’t a cedar. It looks similar to the eastern red cedar, but the berries are smaller. J. monosperma has cones with just a single seed (which is why its common name is one-seeded juniper). Native to the western US and northern Mexico, it has bright blue cones that are about six millimeters in diameter. J. drupacea is native to Europe and is the tallest species, with correspondingly larger berries. They can be up to 30 millimeters in diameter! Alligator junipers (J. deppeana) grow in the southwestern US and Mexico and have very pale blue, nearly white cones that grow up to 15 millimeters in diameter. These puppies are strong in juniper flavor, so watch out! Cones from J. californica are technically edible in that they aren’t toxic, but they’re extremely bitter and generally considered unpalatable. Not all species are edible, however. Do not ever eat the cones from the savin or tam juniper (J. sabina). This is a transplant to the US from China and Europe, and it has a high level of sabinene and sabinol, compounds which are toxic to humans. The cade plant (J. oxycedrus) is also toxic. This plant is rarely found in the US except as an ornamental, but you should still use caution if you aren’t sure which species you’re dealing with. Broadly, plants in the genus can be broken down into Sabina, Caryocedrus, and Juniperus types. It’s those in the Sabina group that should be avoided. You can tentatively identify Sabinas because the leaves are decurrent down the stem, meaning the base of the leaf runs alongside the stem for a bit, rather than extending directly out.

How to Harvest

Early fall through spring is the best time to start your berry-picking adventures in most areas. The female trees are the only ones that bear the fruit (though some trees bear both male and female cones), and the cones usually mature over two or three years, though some species are much quicker. One mature female tree will have fruits of varying age, from brand new to three years old and fully ripe. The males, on the other hand, have pale yellow or brown seed cones with scales that you’ve no doubt seen before. These cones release yellow pollen that can travel for a mile to find a female tree. P.S. The pollen from the male cones of edible varieties is also delicious. Just be sure to wear a mask and clothes you don’t mind getting stained while collecting it in the spring. Don’t worry about stealing all the food from the cedar waxwings and other animals that eat the berries. Each plant produces more than enough to reproduce and feed lots of animals (including humans). Juniper berries should be very ripe before you eat them fresh. Don’t eat unripe berries. An oily berry is a good berry, generally. To harvest, simply grab the ripe fruits and put them in a container, or hold a container below a branch and gently knock the berries loose. Ripe fruits should come away easily. For a larger harvest, lay a tarp under the tree and shake. Don’t eat too many berries all at once because they can be mildly toxic – this goes for all varieties. Don’t worry, many spices that we love can be toxic in large amounts and we just don’t realize it. Nutmeg, for instance, can be toxic in relatively small doses in comparison to other common spices. Communis is the least toxic juniper, with other species varying in toxicity. You can learn more about how to harvest juniper berries in our guide.

How to Use

To store, there is no need to dry them, just put them in an open container until it is about halfway full. You might want to put cheesecloth or cotton over the top to protect from dust or insects. Place this in a cool, dark area. They can last a good, long time this way – a year or more. If you want to dry them, slowly dehydrate them at 95°F until they reach the consistency you prefer. Note that this reduces the essential oils, which is where the flavor comes from. If you want to mix the berries in liquid, don’t use water. The oil from the fruits doesn’t combine well with water, but it does combine easily with alcohol or oil. Traditional uses include spicing game like duck, rabbit, and wild pork with the dried fruits, much as you would season meat with black pepper or as part of a dry spice rub to impart a hint of flavor. They are also a common ingredient when making red cabbage (rotkohl or rødkål), or traditional German sauerkraut. Less often, you might also see juniper beer, which may sound strange, but it makes sense once you realize that the powder on the skin of the cones is actually wild yeast. Some people use this yeast to make sourdough starter, too. If that sounds interesting to you, see our guide to using juniper berries for more tips. Now, juniper doesn’t only work in booze and to flavor meats and veggies. The unique flavor combines particularly well with grapefruit, hard cheese like pecorino, lemon, olive, orange, prosciutto, rhubarb, and sage, so be creative. I also mix the ground dried spice pepper and salt to cure salmon for a homemade juniper gravadlax. The Forager’s Pantry When I was young, my bedstamor (that’s Danish for grandma) would make a trifle with crushed graham crackers and juniper-infused blackberries and raspberries. Delicious! Rene Redzepi, the Danish chef who made New Nordic cuisine famous around the world, frequently uses juniper berries at his restaurants. NOMA: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine During the winter, one of my favorite breakfast recipes is to crush one teaspoon of pink or white peppercorns with a quarter-teaspoon of dried juniper berries in a mortar. I add a quarter cup of rolled oats or soaked rye berries and mix well. Sprinkle the mixture on top of whole, plain yogurt, and add a few blueberries for a little sweetness, if you like. If you use a grinder to chop up the dried berries, be sure to clean the blades every time. They contain a waxy resin that can build up. They deserve to be used in the kitchen way more often! Hopefully now you feel empowered to make them a regular part of your mealtimes. If so, we absolutely can’t wait to hear how you use up your harvest. Do you prefer a traditional meat rub? Or maybe you’re experimenting with juniper-flavored desserts? Let us know in the comments section below! If you want to know more about junipers, you might be interested in some of our other guides on the topic, including:

How to Grow and Care for Juniper ShrubsBlue Star Juniper: How to Grow These Hardy Garden StaplesHow and When to Prune a Juniper Shrub