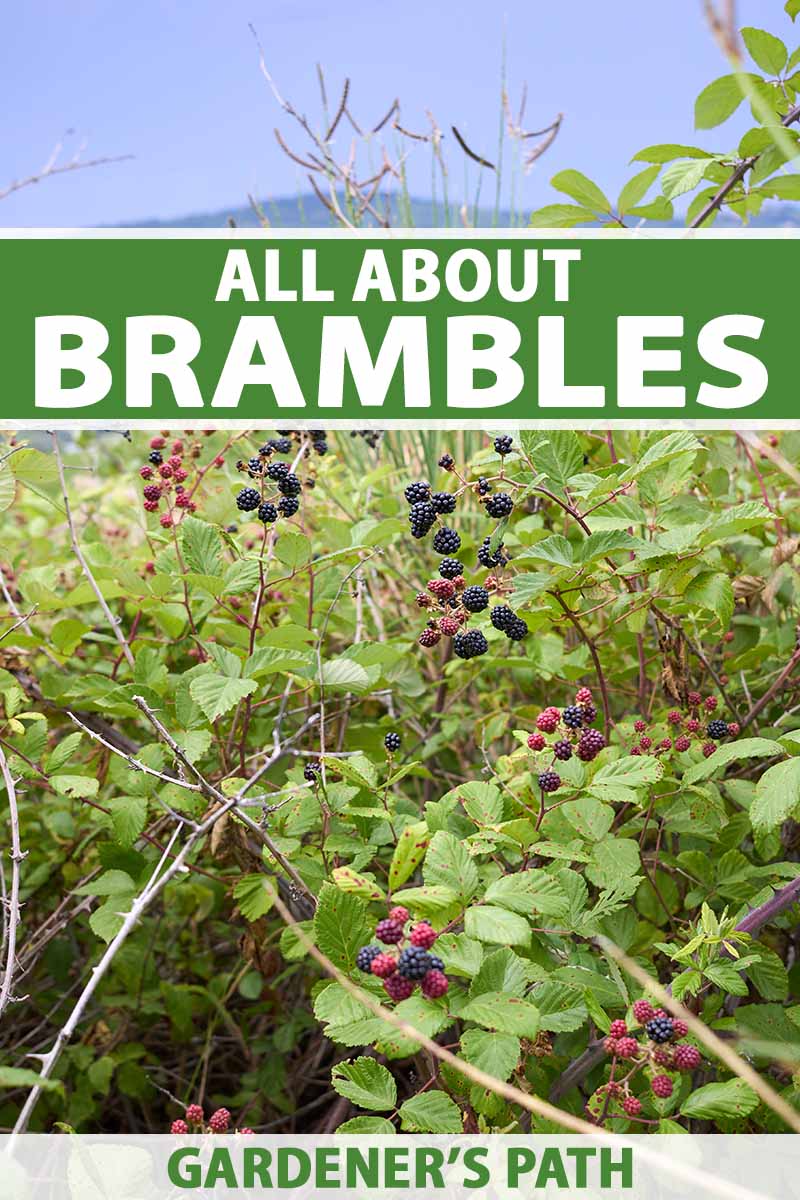

A few minutes later, I found a native blackberry, so I snapped a few pictures to share with friends and recorded the location on my phone. What made finding one member of the Rubus genus so exciting and finding another such a negative experience? Location, location, location. We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission. But they’re not all bad. If you like raspberries, then you know how fabulous these plants can be. It’s similar to how we might call something like amaranth a “weed” when it grows in an undesirable spot, but it’s considered a “crop” or “ornamental” when it’s cultivated in a location where we want it to grow. Coming up, we’re going to dive into the wild world of brambles to really figure out what they are. Here’s what we’ll discuss: Ready to get your fingers figuratively stained? Let’s go!

What Is a Bramble?

The term bramble basically refers to anything in the Rubus genus. There are over 200 species that fall into this category, including one plant that is actually called a brambleberry (R. arcticus). In the UK, it’s R. fruticosus that people refer to in this way. In the western US, it’s generally the Himalayan blackberry (R. armeniacus) that earns the epithet. The origin of the word bramble comes from Old English and translates to something like “broom.” All of these plants are perennials that act as biennials – while the crowns and roots are perennial, the canes are produced on a two-year cycle. The plants produce a primocane in their first year, which develops into a floricane in the second year, and this is where the fruits form. Humans have cultivated some types of raspberries from a genetic mutation to develop fruits on the first year’s canes, but otherwise, all fruits come from two-year-old canes. A Botanist’s Vocabulary All species within the genus can cross-breed or be hybridized, which is how we’re able to enjoy plants like loganberries, boysenberries, tayberries, and marionberries today. When someone laments the brambles in their yard, they’re usually referring to an invasive species that has large thorns. And people don’t mean it in a positive way – think “I can’t believe how much of the side yard the brambles have taken over this spring!” rather than “gosh, I’m so happy to see all of these brambles that have started growing in the rose garden!”

Common Species

If it produces biennial canes, thorns, and berries, it’s likely a bramble. Here are some of the most common species:

American red raspberry (R. strigosus)Black raspberry (R. occidentalis)Boysenberry (R. ursinus x R. idaeus)Canadian blackberry (R. canadensis)Cloudberry (R. chamaemorus)Common blackberry (R. allegheniensis)Creeping raspberry (R. calycinoides)Cutleaf blackberry (R. lacinatus)Dwarf red blackberry (R. pubescens)European blackberry (R. fruticosus)European dewberry (R. caesius)Himalayan blackberry (R. armeniacus)Loganberry (R. x loganobaccus)Marionberry (R. ‘Marion’)Mountain raspberry (R. fraxinifolius)Northern dewberry (R. flagellaris)Red raspberry (R. idaeus)Salmonberry (R. spectabilis)Stone bramble (R. saxatilis)Tayberry (R. fruticosus x R. idaeus)Thimbleberry (R. parviflorus)Trailing blackberry (R. ursinus)Western blackberry (R. leucodermis)Wineberry (R. phoenicolasius)Yellow raspberry (R. ellipticus)

Blueberries aren’t brambles, and neither are roses, though roses are part of the same family as brambles (Rosaceae).

Growing Requirements

Of course, every species is slightly different, but all brambles have fairly similar requirements. They like lots of moisture, but they also need to be planted in well-draining soil. Most need full sun, though some do well in partial sun. There are a few species that can grow in shade, such as salmonberries. Most are self-pollinating, but some need a companion to cross-pollinate and produce fruit.

Removal Tips

If you have these plants growing in a location where you don’t want them, it’s probably best to pack up your stuff and burn your home and yard to the ground. Okay, I kid! Sort of. If you’re looking for a less extreme (and less effective) method of control, there are a few possible lines of attack. First, take immediate action the second you spot a cane. Dig all around it and pull the whole thing up, roots and all. Quick action is key. A cane can reproduce anywhere it touches the ground, and over 500 canes can grow in just 10 square feet. A thicket of canes can produce up to 13,000 seeds. You can probably see how things can rapidly grow out of control. If a thicket has already started forming, dig up as much as you can and remove as many of the roots as possible. Every chunk of root you leave behind can form a new cane. Next, cut down any canes that form over the next few months. You can do this individually or use a mower or weeder to slice them down. You must be consistent and stay on top of things. Eventually, the roots will be starved and the plant will die. Livestock grazing is also extremely effective. My neighbor managed to tackle an acre of thick, unwanted growth by bringing in cattle and goats. It took several years, but they are bramble-free now. If you go this route – and you can rent animals in many locales if you aren’t looking to keep livestock – protect any trees or shrubs that you want to keep using fencing, since these animals can be pretty indiscriminate about what they eat. To be honest, I’m actually happy to see Himalayan blackberries in the late summer when the fruits are ripe. And I’m always overjoyed to find a wild raspberry bush. But I’m less happy when I see a cane creeping up in my carefully tended veggie garden, regardless of which species it is. What about you? Are you planning to plant any Rubus species? Or are you looking to get rid of one? Let us know in the comments. If you want to enjoy all the good things that the Rosaceae family has to offer, you might want to read these guides next:

How to Grow and Care for Spirea BushesHow to Plan a Rose GardenHow to Grow Flowering Quince for Early Spring Color